The Age of the Anti-Monument

Reviews, Joen Vedel 03.05.2022

The age of monuments is over and as a result history is free to move again. Over the past few years, statues of powerful figures have been toppled from their plinths all over the world, one after the other, their heads twisted from their bronze bodies, which have been doused in paint and dumped in rivers. The message is clear: politicians, slave owners, and perpetrators of genocide can no longer take their places in public spaces for granted. Their violent actions have not been forgotten and now at last the time has come to revoke the tribute paid to them.

In the slipstream of this wave of statue topplings and protests comes the exhibition Anti-Monument, the largest and most significant part of this year’s Hannah Ryggen Triennale. Curator Solveig Lønmo has used the three venues of Gråmølna, the Hannah Ryggen Centre at Brekstad, and Austråttborgen in Ørland. The tone of debate is set in the opening text to the exhibition: “What is a hero; what is a nation, and how can we be pushed to look in new directions to shape a less conform and authoritarian future?” asks Lønmo. These are questions that require us to take a stance again and again, and which never become obsolete. As everyone knows, war has broken out in Europe and war brings with it an increase in nationalism, misogyny, natural disasters, and militarisation. For this reason, it is crucially important to insist on the opposite: international solidarity, feminism, environmental awareness, and love. Four values that Hannah Ryggen for one exemplified in her art.

In 1924, Hannah Ryggen moved to Ørland. On her modest small-holding, she developed her own idiom and experimental weaving techniques, using materials largely sourced from the area where she lived. She hand-spun her own yarn using wool from local sheep, then dyed it using wild plants, moss, birch leaves, and urine. In this way, Ryggen’s working process established a symbiotic relationship with the nature that surrounded her, which she quite literally wove into her fabric, thread by thread. But it wasn’t only through her craft methods that Ryggen expressed an ethical standpoint. Her motifs also bear witness to a deep engagement with the political circumstances of the era in which she lived. Those of her works that feature in the exhibition provide us today with a point of access to many of the most dramatic events and conflicts of the twentieth century. As subjective statements and historical documents, they articulate a perennially relevant ethical and aesthetic challenge: how can we capture social and political transformations while they are still ongoing?

Works such as Liselotte Hermann and Drømmedød (Dream Death), on display in Gråmølna, are direct commentaries on some of the horrors that took place during the years Hannah Ryggen lived at Ørland. In so many of Ryggen’s tapestries, the theme she seeks to process is war and its impact on the individual. Enraged by newspaper articles and radio reports, she found a thoroughly unique way to respond, one that reflected an awareness both of her position as a commentator and of her remoteness from the violence she depicted. In step with the news media’s ability to report directly from conflicts around the world, thereby bringing them directly into people’s homes, Ryggen chose to use the labour-intensive and technically demanding medium of weaving to express her resistance and solidarity – a choice which in itself marks a form of resistance to the temporality of war and an insistence on the local.

One of Ryggen’s monumental tapestries now on show to the public at the Hannah Ryggen Centre in Brekstad is Etiopia (Ethiopia). When it was shown for the first time at the World Exposition in Paris in 1937, it hung beside Picasso’s celebrated Guernica. Both works were created as reactions to the violence of fascism, but while Picasso’s abstract statement quickly gained the status of one of the most important anti-war paintings of all time, Ryggen’s work – with Mussolini’s severed head on a spear – was considered too radical and direct in its critique, with the result that the tapestry was censored and the offending part discreetly folded out of sight. A similar fate would also befall Picasso’s Guernica many years later, when the Americans insisted on covering it where it hung in the UN headquarters, before informing the world of their invasion of Iraq in 2013. Both of these episodes are indicative of how the holders of power sometimes resort to frantic measures to control the narrative about contemporary events and to manage the means of symbolic production, while at the same time testifying to the significance and potential of art to critique that power.

Since so much of the material in the exhibition is selected from Nordenfjeldske kunstindustrimuseum’s unique collection of works by Hannah Ryggen, it is Ryggen’s practice that forms the focal point for the discussion about the anti-monument. There is no reason why this in itself should be a problem, but given how uncomfortably relevant Ryggen’s works and idiom seem to us today, it is easy to overlook many of the other works as superfluous. At Gråmølna in particular, the hanging seems too dense and haphazard, with the result that in places the exhibits end up getting in each other’s way. Which is a pity, because by and large Lønmo succeeds in creating a fine hand-spun thread to bind the works together, and in particular those of Hannah Ryggen, Britta Marakatt-Labba, Arthur Jafa, and Jonas Dahlberg. The exhibition is at its strongest at the point where the thread begins to fray and to expose the monument’s attempt to round things off, the point at which the viewer is invited to join an unresolved debate, a movement, to entertain doubt; to enter a conflicted space that acknowledges itself as already and always an arena of violence.

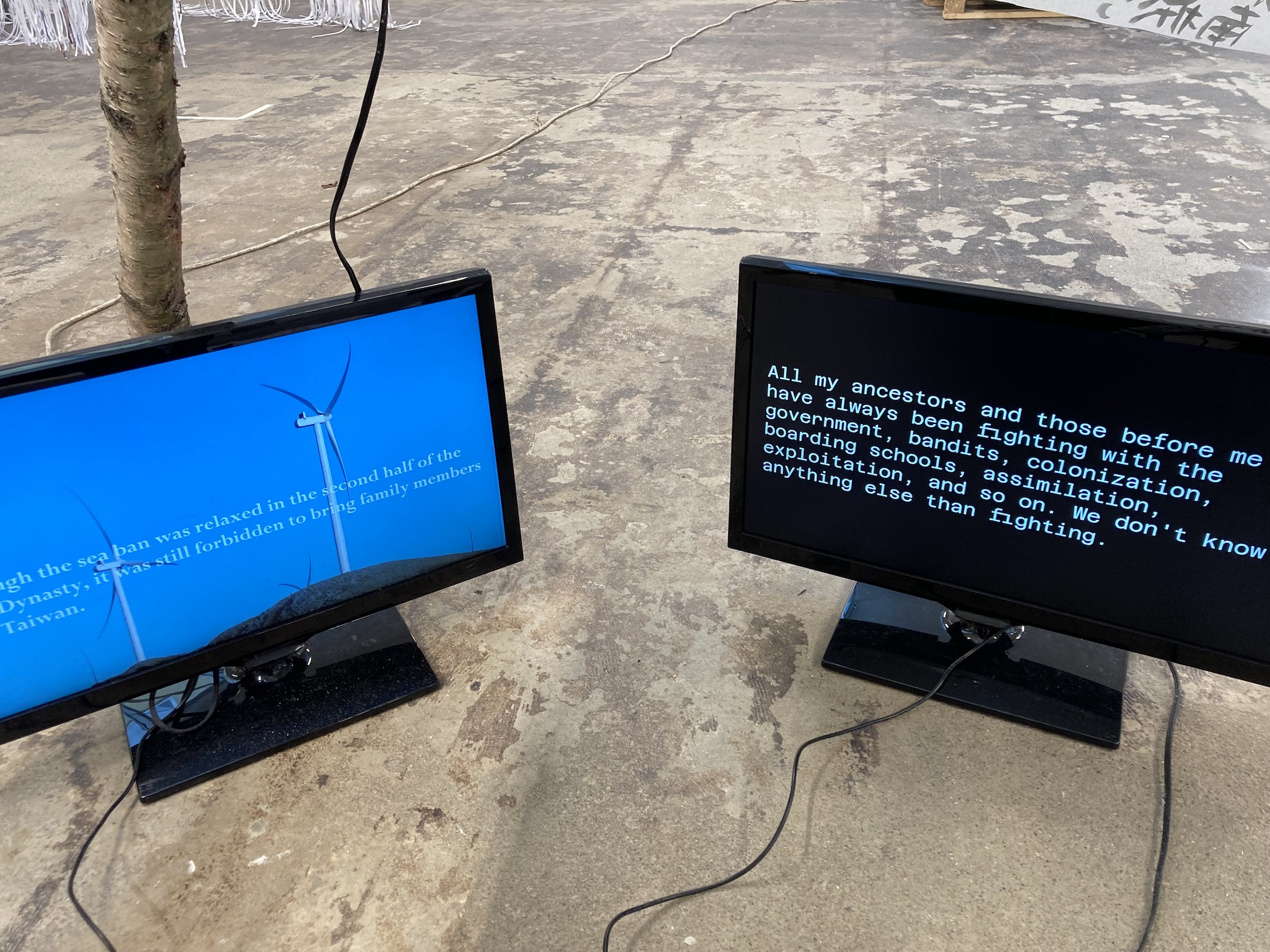

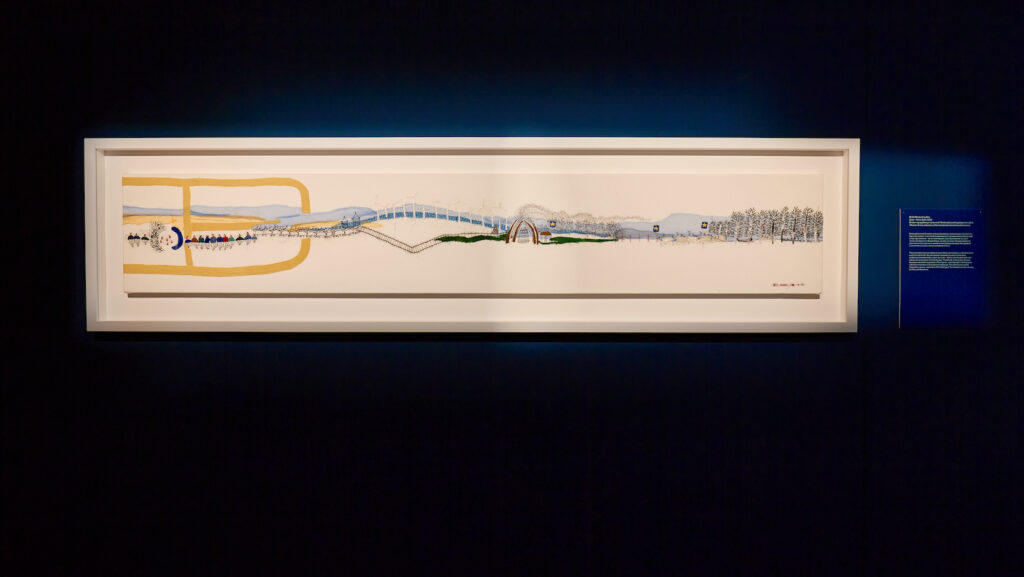

With her intuitive embroideries, Britta Marakatt-Labba is the artist who comes closest to Hannah Ryggen in terms of form. But where Ryggen is motivated by indignation at the political events of her time, Marakatt-Labba bases her work on a Sami history that others have tried to erase. But where should one begin when narrating a history which for so long people have been forbidden to tell? In the work Datid – Nutid (Past – Present), one can see every point where the needle has been pulled through the fabric, slowly contributing to the depiction of a figure, a reindeer, or a windmill on the empty snow-white background. The landscape is broad, the sky low, and between the tiny stitches a story emerges that negates the notion of linear time and turns the idea of progress on its head. Here there is no clear beginning or end, no homogenous or unified culture, just a complex movement up through the ages, where Sami traditions and rituals are confronted with raw industrialisation and the modern exploitation of natural resources, without any kind of resolution.

Just as the stitches in Britta Marakatt-Labba’s work emerge from a historical void, slowly bringing forms to light through the encounter with their contradictions, the images and editing of Arthur Jafa’s video work The White Album also convey a world in conflict. Here we are shown a flow of carefully selected found video clips, mixed with Jafa’s own recordings, which gradually take us deeper into a fragmented society, characterised by deep mistrust between social groups. As if struggling to maintain a balance, Jafa sets up a tone and tempo only to knock it down again, so that we never arrive at a predictable and comfortable beat we feel we can simply roll with. In sequence after sequence, we are constantly overtaken by Jafa’s convulsive rhythms, which force us into a prolonged encounter with the darker recesses of the Internet, a material also referred to as snuff and which many of us strive to avoid. The White Album is an essay, a poem and a portrait that punctures – but without quite dismantling – the whiteness around which History has been constructed.

Jonas Dahlberg’s sober essay film, Notes on a Memorial, takes a more restrained approach, inviting the viewer into the artist’s work process as he develops two public memorials for the victims of the 22 July 2011 terror attacks, one on Utøya, the other in the Government Quarter in Oslo. For his project Memory Wound, he wanted to cut a channel through the Sørbråten peninsula that looks across to the island of Utøya, in order to create a void, a cut in the physical landscape. As is well known, the project was never realised because local residents banded together in protest. As a proposal for a memorial, they considered it too brutal. The intervention was too big, and the locals didn’t want to be confronted with the tragedy on a daily basis. In a didactic style, Dahlberg takes us by the hand and guides us through his work process, which lasted more than four years. Along the way, we are shown satellite images with red markings, graphs, and illustrations, and get to hear his personal reflections on the problems of commemorating pain and grief. Dahlberg’s essay film is in itself an anti-monument, a fascinating narrative about the relationship between collective and personal grief, and about the potential of art to inspire a public debate about how we should remember what happened and must never happen again.

Although the exhibition presents many exciting contributions to the debate about monuments and memorials, clearly it does not allow us at this stage to draw any conclusions. Nevertheless, Hannah Ryggen’s Vi Lever på en Stjerne (We Live on a Star) can be viewed as the exhibition’s undoubted masterpiece and as an unsurpassable example of an anti-monument. In stark contrast to Ryggen’s earlier anti-fascist works – uncompromising ripostes to the violent conflicts and the horrors of war that happened during her own lifetime – this 3×4 metre work stands as a poetic tribute to humanity. The tapestry shows a naked woman and man in a loose embrace, surrounded by stars, planets, faces, and hands that touch and gesticulate. Originally commissioned for the government building in Oslo in 1958, the work was badly damaged during the fascist terror that hit Norway in 2011, suffering a tear in the lower right section that had to be sewn back together. The traces of the bomb attack are still visible between the threads that Ryggen wove, like a scar that is slowly healing, a reminder that the fight against fascism is still ongoing and that peace can never be taken for granted.

During the vernissage at Gråmølna, I noticed how people crowded around the work to inspect the damage, as if attending to a shared open wound. What these layers of plant-dyed, hand-spun yarn convey to us is not just of Ryggen’s poetic optimism, but also the vulnerability of our planet and the more sickening aspects of humanity. In the context of this exhibition, the work possesses a materiality that can accommodate the great contradictions of life while also providing ample scope for both the processing of trauma and the nurturing of hope. By taking this work as the focal point for the exhibition, Lønmo successfully creates a framework for complex questions about the relationship between art, violence, and memory. The anti-monument is a phenomenon that forces us to confront history’s darker chapters and – not least – to adopt a position in our encounter with them. In a time when war seems once again to be drawing closer, Anti-Monument helps to show that, even if the era of monuments is over, the horrors of history must not be forgotten. Art can be used to keep the conversation about grief and dreams alive.

Hannah Ryggen Triennale 2022

Anti-monument

25 March–14 August

Arranged by Nordenfjeldske kunstindustrimuseum

Original text translated by Peter Cripps / The Wordwrights