A Dive Into the Human Mind

Reviews, Heidi-Anett Haugen 30.06.2022

A large picture of a young woman in a hijab is mounted high up on the façade of K.U.K. The work has the title Hani. She is shown three-quarter face, looking to the left. Measuring 200 x 305 cm, the work uses a landscape format and consists of three aluminium panels. Initially I assume the picture to be black and white, but on closer inspection the surface turns out to be entirely white. The appearance of black or grey is produced by the shadow of the brick wall behind the image, visible through perforations in the metal. This technique has been a characteristic of Anne Karin Furunes’ works since the mid-nineties.

The exhibition Rippling is produced by the artist and professor at the Trondheim Academy of Fine Art, Anne-Karin Furunes. Nine other artists have also contributed, including former colleagues and students, their works engaging in dialogue with those of Furunes herself. With seventeen works by Furunes and twelve by the other nine artists, the show encompasses a total of twenty-nine exhibits. The predominance of work by Furunes means that I too find myself focusing mostly on her production. It isn’t until I step into the innermost room of the venue, the so-called Bingo Hall, that I encounter a work by another currently living artist.

At first glance, it is easy to believe that Anne-Karin Furunes’ pictures must have been created using rasterisation. In other words, that the half-tone areas have been converted from pixels to dots using, for example, Photoshop, and that these dots, also called rasters, have been turned into perforations by means of a machine. The many small holes help to create the image, producing a clearly graphic effect. A sense of 3D. An impression of something digital. This could also have to do with the fact that the motifs are taken from photographs. But the receptionist at K.U.K tells me that Furunes does not use digital tools such as Photoshop to convert her photographs from pixels to rasterised dots. She simply studies the picture and draws the dots where they need to be before printing them by hand. Which is pretty impressive.

Hanging in a row out on the façade are three flags, just above the window of the Gubalari restaurant. Each flag is wrapped around a flagpole, suggesting to me a keffiyeh, the traditional Arab headdress otherwise known as the “Palestinian scarf”. The reason for this association is the black and white pattern on the flag. The pattern itself consists of round raster points, which I suspect collectively form a portrait. The title Thora Storm refers to a local school headmistress, women’s rights campaigner, and local politician in Trondheim. So what we have here is a portrait of two women, Hani, whose name is unfamiliar to me, and Thora Storm, whose flag has clearly been exposed to a storm. Should they be wound around the flag poles in the way they are? I’m tempted to straighten them out.

In the Corner Gallery to the left hangs the work Schweden (Sweden) by Hannah Ryggen. Deeper into the room we encounter a huge picture on canvas, a full 6 metres high and 2.4 metres wide. The canvas is covered in black acrylic paint. Here too the technique consists of perforation. It is the picture of a woman whose gaze seems to follow me as I move around the room. This impression can be attributed to the fact that she is looking straight ahead. My brain interprets her gaze as directed at me, with the result that, no matter where I move in the room, she seems to be observing me. It is an optical illusion that produces a sense of three-dimensionality even if the image is flat. The work has the title Anna Lisa, which might be a nod to Leonardo da Vinci’s universally famous Mona Lisa, who also has a gaze that follows the viewer. There is a contrast here between the fact that I don’t know who Anna Lisa is, whereas I do know who Mona Lisa was, or at least, who she might have been.

The room known as the Back Yard is a challenging space, because it feels like a vestibule or foyer and is dominated by a number of tables and leather-covered armchairs that stand relatively close to one of the works. It also accommodates the reception area, an entrance to the restaurant, stairs down to the basement, and stairs up to the art shop. The work has a lot to compete with in this foyer area. Here we find four works by Furunes. Once again, pictures based on perforation, although this time three of them have nature as a theme. The fourth is a portrait of a child with a short haircut, seen in profile, looking to the left.

The Bunker is the room which to my mind works best. This houses another four works by Furunes. Here the perforation is so effective that one has the impression of looking at big screens. Furunes has perforated monochrome surfaces with holes of different sizes, with the larger ones producing paler, the smaller ones darker areas. I wonder how she transfers her motifs to the canvas. How she knows where to cut each hole. I don’t understand how it’s possible to do this by hand, but I’m equally fascinated by the way mere holes of different sizes can add up to a picture.

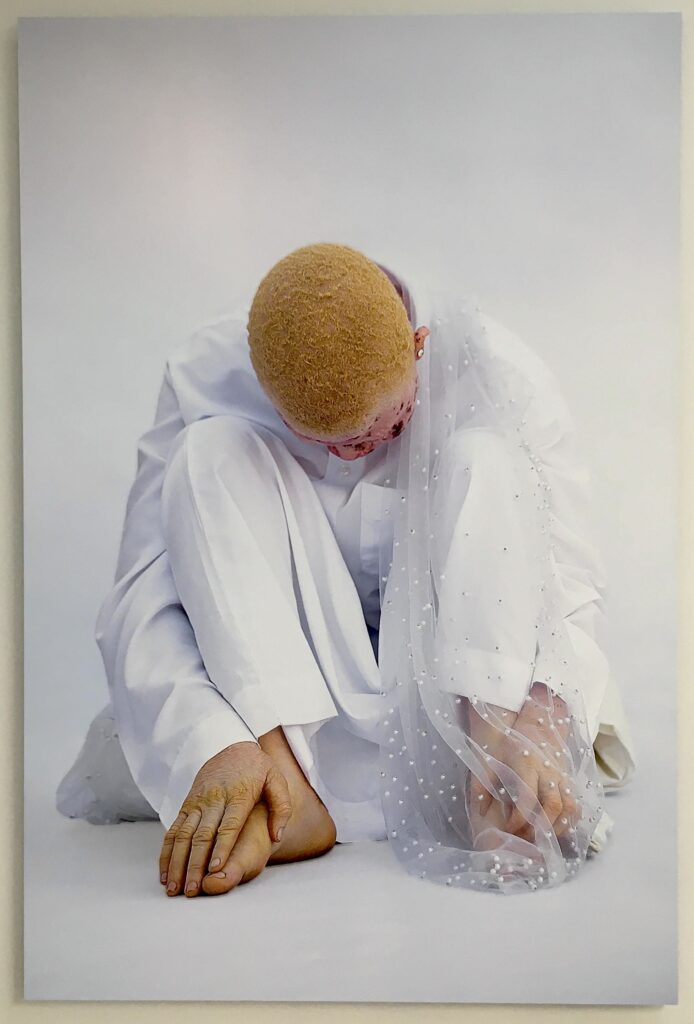

On the way into the Bingo Hall one finds Astrid Ljungberg’s De brister tidigare och tidigare (They Break Earlier and Earlier). Square pieces of chicken wire covered with newspaper and painted white are coiled together to form an arch that reaches from the floor to the ceiling, forming a portal through which one passes when entering the next room. On the left hangs a photo by Laura-Ann Morrison. Printed on aluminium, the picture has the title Ya pu no, yɛ n’dɔ no – The rejected daughter. The image makes a powerful impression. It shows a woman sitting on the ground, her knees pulled up in front of her, her hands on her feet, and her head facing downwards. She appears to have albinism and is dressed in a white suit or dress. Draped over her left shoulder is a veil embroidered with white pearls. Her short hair, hands, and feet have a yellowish hue. Albinism is a genetic condition that impairs the body’s ability to produce pigment in the skin. In Malawi in 2014, at least 59 people with albinism were attacked and eighteen of them killed, according to Amnesty International. Their body parts are coveted by so-called witch doctors. Working with what people perceive as different and tend to reject is something Furunes and Morrison have in common. Furunes has worked with image archives from mental hospitals, for example in Back to Light. Faces reflecting the past at San Servolo Mental Hospital, which can be seen on the Sculpture Roof.

In a corner just beyond Morrison’s photograph we find the installation Parasympathetic Shadow Play by Meerke Laimi Thomasson Vekterli. Stretched out from the ceiling is an expanse of white fabric shaped like an animal skin with fringed edges. Behind it is a little thicket of twigs mounted on a rotating disc on top of a birch stump. Illuminated by two small spotlights, the moving twigs create a shadow play on the stretched fabric. It is a work that strikes a fine balance between artificial scenography and simple technology. The shadow play reminds me of falling asleep as a child, when cars passing by on the road outside cast the shadows of branches on my bedroom curtains. Light and shadow are central elements of this installation. One could perhaps say that there is a link here to the work of Furunes, not just in the use of light and shadow, but also in the way both artists retrieve forgotten memories from darkness. The parasympathetic nervous system becomes active primarily when one is relaxed. Parasympathetic stimulation lowers the heart rate.

Hanging on the walls in the Bingo Hall are three works that show glaciers at the moment of calving. The pictures appear to be taken from old print newspapers. In each image, the colours R, G, B (red, green and blue) are separated. Each colour is a circle and here again there is the use of perforation. I can almost hear the crash of the glacier as it calves. It would definitely have been a noisy moment. The image is like a still from a film. It makes me want to rewind, but it can’t be done. I notice the picture is in colour. Could that have to do with the fact that it is about the here and now? And the future? Whereas the portrait and some of the other nature images are black because they use material found in archives and represent unknown memories? The title of the exhibition is Rippling, which conjures up small waves on water. But when a glacier calves, a block of ice breaks off and hits the water, an event that can result in huge waves.

A few floors higher up there is a roof terrace with several sculptures. In addition to Furunes’ Back to Light. Faces reflecting the past at San Servolo Mental Hospital there is a birdhouse by Oscar Eriksson Furunes and Juho Eerola. The title of the work, The Birds / Fuglene, echoes that of the 1963 film by Alfred Hitchcock. In the latter, nature goes on the attack. In one scene, one of the central characters is attacked by birds while locked in an attic. The scene took a week to film. Apparently the birds were tied to the actress by lengths of elastic, thus preventing them from flying away and leaving them no choice but to attack. In the work on the sculpture roof, one hears the sound of birds inside the birdhouse, or is it humans imitating birds? At times the noise degenerates into a cacophony, yet no birds come flying out to attack us. Is it a house or a cage?

The exhibition Rippling is extensive, largely because of the architectural circumstances. The best parts, in my view, are where the works of Furunes are grouped together. In her portraits, Furunes often focuses on vulnerable, forgotten women. I am left wondering what happens when you turn a spotlight on these unknown people. Are they random, anonymous women who feature in these pictures? And what about the order in which they are shown? How should I read them as a narrative? Do they represent a glimpse of lost memories, or rather a dive into the human mind?

I am unsure about the dialogue between the works by Furunes and those of the other exhibitors. This is probably because there are so many by the former and her technique is so striking. Several of the abovementioned works by the invited artists are individually very good. Whether as spatial installations or as pictures with powerful motifs, they manage to hold their own beside Furunes’ perforated works. The preponderance of works by Furunes, and the fact that it is these one encounters first on entering the venue, leaves me feeling that this could well have been a solo exhibition or a retrospective.

Rippling

Anne-Karin Furunes, with Nina Roos, Marko Vuokola, Edvine Larssen, Laura-Ann Morrison, Astrid Ljungberg, Meerke Laimi Thomasson Vekterli, Oscar Eriksson Furunes, and Juho Eerola. The exhibition is part of the Hannah Ryggen Triennale 2022.

11.06.–22.08.2022

Kjøpmannsgata Ung Kunst

Original text translated by Peter Cripps / The Wordwrights