Artistic research and new fantasies

Interviews, Kunstnerisk forskning under lupen!, Joen Vedel 31.03.2023

Artistic research has been an integral part of art for as long as art has existed, insofar as any artwork presupposes enquiry and the development of a method before it can take shape. Even so, in combination, the two words “art” and “research” can still trigger heated debate among artists and researchers (and between them and art historians), as they tend to do every few years. It is a debate that is generally approached with a defensive attitude, because someone believes that art – or research – is under attack and needs to be protected so that it can remain as it is. Within the art world, this defensive (read conservative) position has often been characterised by a pronounced fear that academic disciplines pose a threat to something as sacred as “artistic freedom”, although in the context it is rarely questioned what this kind of “freedom” entails. Conversely, in the academic world one notices a fear that that self-same “artistic freedom” could dilute academic disciplines and methods in ways that undermine the authority of scientific results, albeit without adopting a critical approach to the universal concept of truth on which that authority depends.

In recent years, the fear that artistic research will intellectualise art and render it academic (whatever that may mean) has found expression notably in Scandinavia, where conservative voices such as the former Danish Minister of Culture, Joy Mogensen, and the Swedish critic Lars O. Ericsson, have weighed in on the debate with attempts to pin down a contradictory relationship between artistic research and artistic practice; between craft on the one hand and the theoretical and knowledge-based on the other. Behind this fear, one senses conceptions of the artist’s role and the artwork that were current in the pre-impressionist era. Rather than approach artistic research with curiosity and asking how it operates and what it can contribute today, these conservative forces focus on the issue of definitions and boundaries between various traditions. In other words, they hold the debate back in a boring and unproductive place from where I suggest we move on. And for the same reason, I also prefer not to offer any kind of definition of what artistic research is in this text. Because, just as there is no one way to make art and no singly valid form of research, neither is there just one way to conduct artistic research. Which is precisely where the potential of artistic research lies – in its capacity not to conform to a prescribed method, but to contribute to the development of new methods, new forms of learning and new approaches to aesthetics.

When I met with my colleague from the Trondheim Academy of Fine Art, Professor Nabil Ahmed, to discuss artistic research, we quickly agreed to take Nabil’s practice as a starting point for an attempt to demystify what artistic research can be. Nabil moved to Trondheim three years ago, to continue his practice with INTERPRT, a research and design group that he leads together with Olga Lucko and part of the burgeoning research community at the Academy of Fine Art, to which I myself belong. Over the years, INTERPRT has focused on what is known as ‘climate-justice’ and the investigation of environmental crimes, using spatial and visual studies that reach well beyond any kind of ‘art for art’s sake’, in the sense that they use art to engage with social structures and to venture into the spheres of power. In effect, INTERPRT’s research work involves an array of collaborations with different disciplines and professionals, ranging from architects and designers to lawyers, academics and activists. In many respects, INTERPRT is a standard-bearer for precisely this kind of interdisciplinary research.

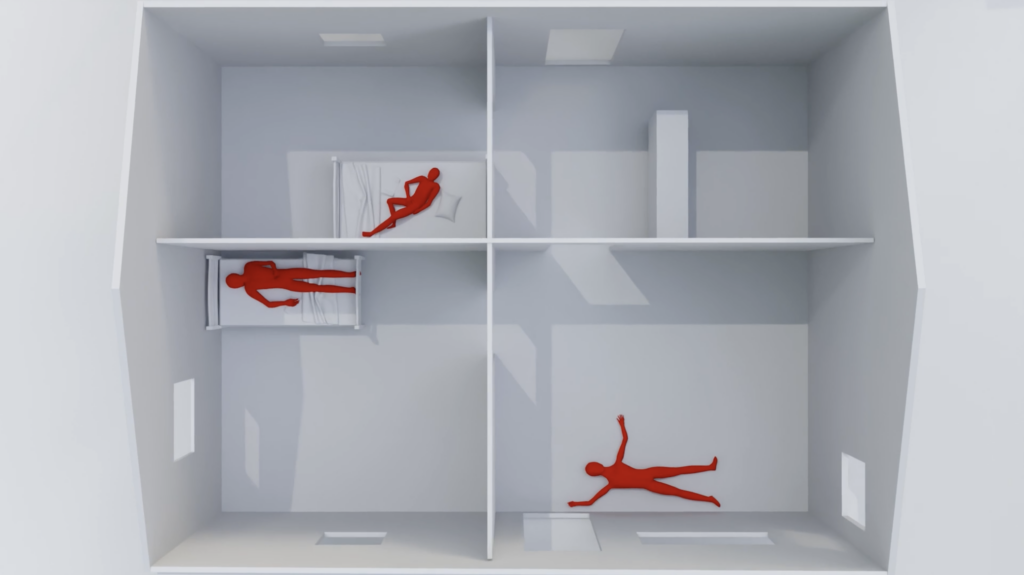

“In our work, research is a highly pragmatic endeavour, where the primary concern is to explain how we get from A to B and all the steps that journey involved,” says Nabil. “For us, it has less to do with burying ourselves in books, as so many academics do, and is more a question of developing techniques that allow us to give form to complex phenomena – just as a painter or a sculptor does – where every line and detail has a meaning, where every distance and relationship between image and object, space, resolution and materiality is truly significant, to the extent that the incorporation of any item as evidence can become a matter of life and death.” As in much of the artistic research being done today, what we are dealing with here are critical concepts of aesthetics and the artwork that refuse to be constrained by ideas of art as something autonomous that is created in a studio in isolation from the outside world and then displayed exclusively in a white cube. By contrast, INTERPRT’s artistic practice is largely about participating in established social structures using aesthetic techniques to present evidence that can help to ascribe responsibility, for example, in cases of environmental crime, and hence to foster genuine change for social groups exposed to various forms of injustice. This kind of research requires, in equal measure, precision in the verification of facts and a deep commitment to experimentation with aesthetic forms.

Nabil completed his doctorate at the Centre for Research Architecture at Goldsmiths in London, where he helped establish the pioneering agency, Forensic Architecture, together with Eyal Weizman and others. At a round table in a loft space at Goldsmiths, a group of PhD students, activists, artists and academics met to further develop what has since become known as ‘the forensic turn’, a strategy that employs many of the same technologies that the powers that be use to oppress people – technologies such as mass surveillance and biometric data collection – and redirects them against those same oppressive powers in an effort to establish counter-evidence in cases of injustice. With the help of a European Research Council (ERC) grant awarded to Weizman, Forensic Architecture was established in 2010, in the same building that had housed the Young British Artists movement thirty years before. Whereas in the 1990s, Damien Hirst and his fellow students had represented a cynical response to the egocentric, market-driven logic of neoliberalism, Weizman and Forensic Architecture represented a collective, research-based form of political engagement that positions itself in the field between art, architecture, design, investigative journalism, law and media science, and which works in close collaboration with human rights organisations and activists from every corner of the globe. In Nabil’s view, this direction in art can be traced back to the documentary and socially-oriented practices pioneered by artists such as Harun Farocki, Martha Rosler and Allan Sekula. But whereas much of the earlier socially engaged and research-oriented art was about holding up a mirror to those in power or creating awareness for specific issues, Forensic Architecture and INTERPRT have gone a step further by collecting evidence that can help to hold those in power legally accountable for their actions.

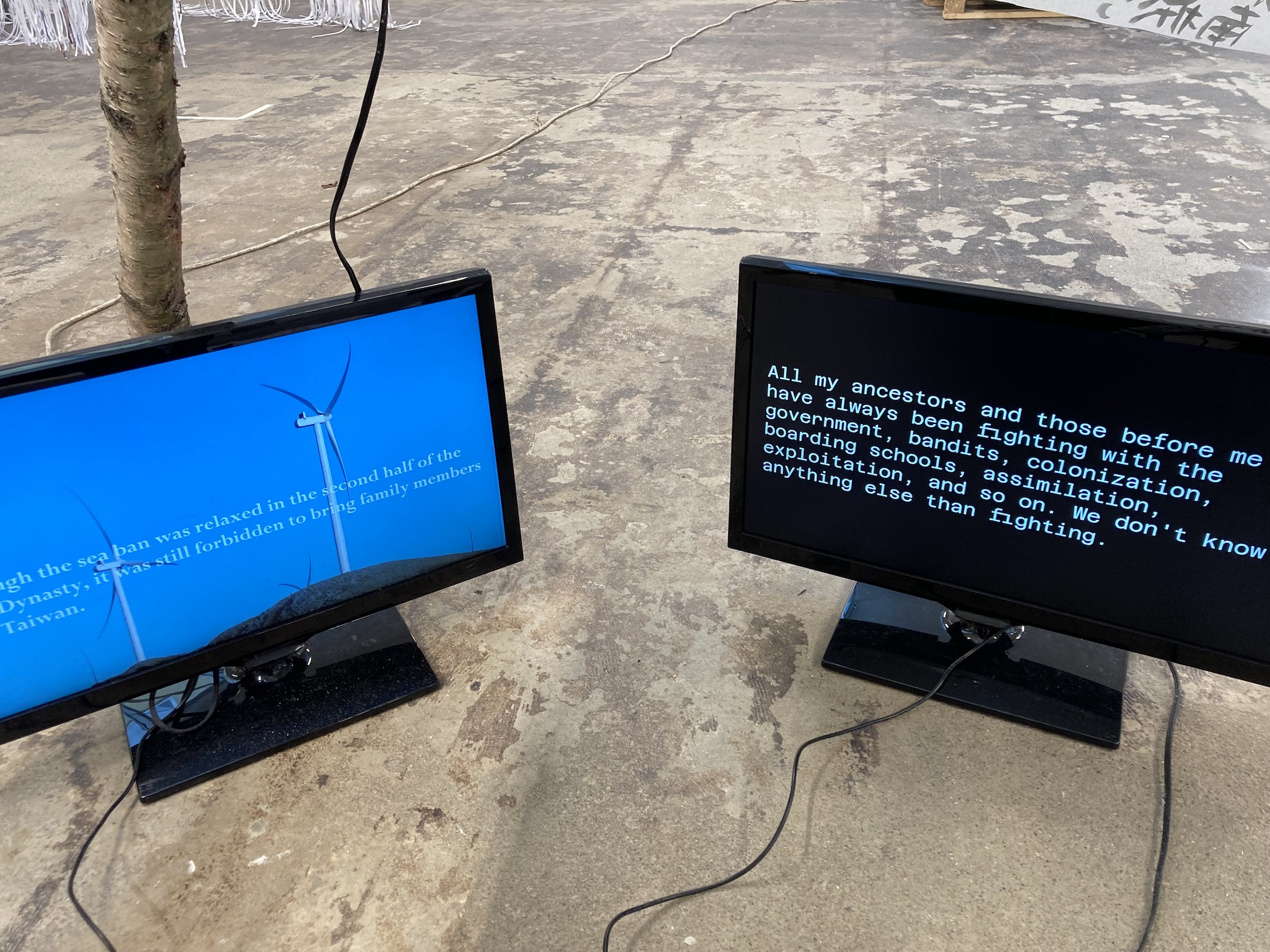

For INTERPRT and Nabil Ahmed, the ultimate objective is neither research nor art as such, but rather an ongoing quest for the most effective way to communicate their research, using not just the channels of the classic exhibition format and online fora, but also in some cases the kinds of evidential material used in litigation against states or large multinational corporations. “For us, the motivation is that there is no other way,” says Nabil. He continues: “Certain injustices must be brought to light and we seek to use the tools at our disposal to support various groups in their struggles. And these are not always the same. They vary from place to place, from one dispute to another. Sometimes we miscalculate, or it proves more than we can handle. But the important thing is to keep moving between inventiveness and the refinement of certain methods, tools and communication strategies. It’s all about gathering counter-evidence and making our findings available to the public. And in some cases, this is where the exhibition has a part to play, as a medium that allows us to bring various elements of the work together and to experiment with form and idiom.” Accordingly, over the years, INTERPRT has presented its work at events and venues such as MACBA in Barcelona, CCA in Singapore, the Warsaw and Istanbul biennials, and Bergen Kunsthall. In summer 2023 the group will participate in the Helsinki Biennial, with a project that addresses violations to the rights of the Sami population.

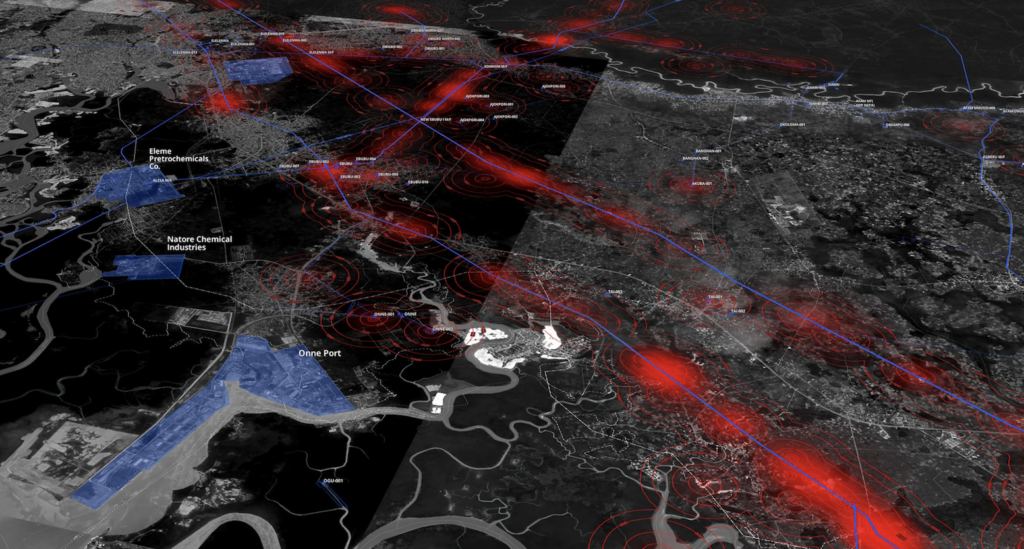

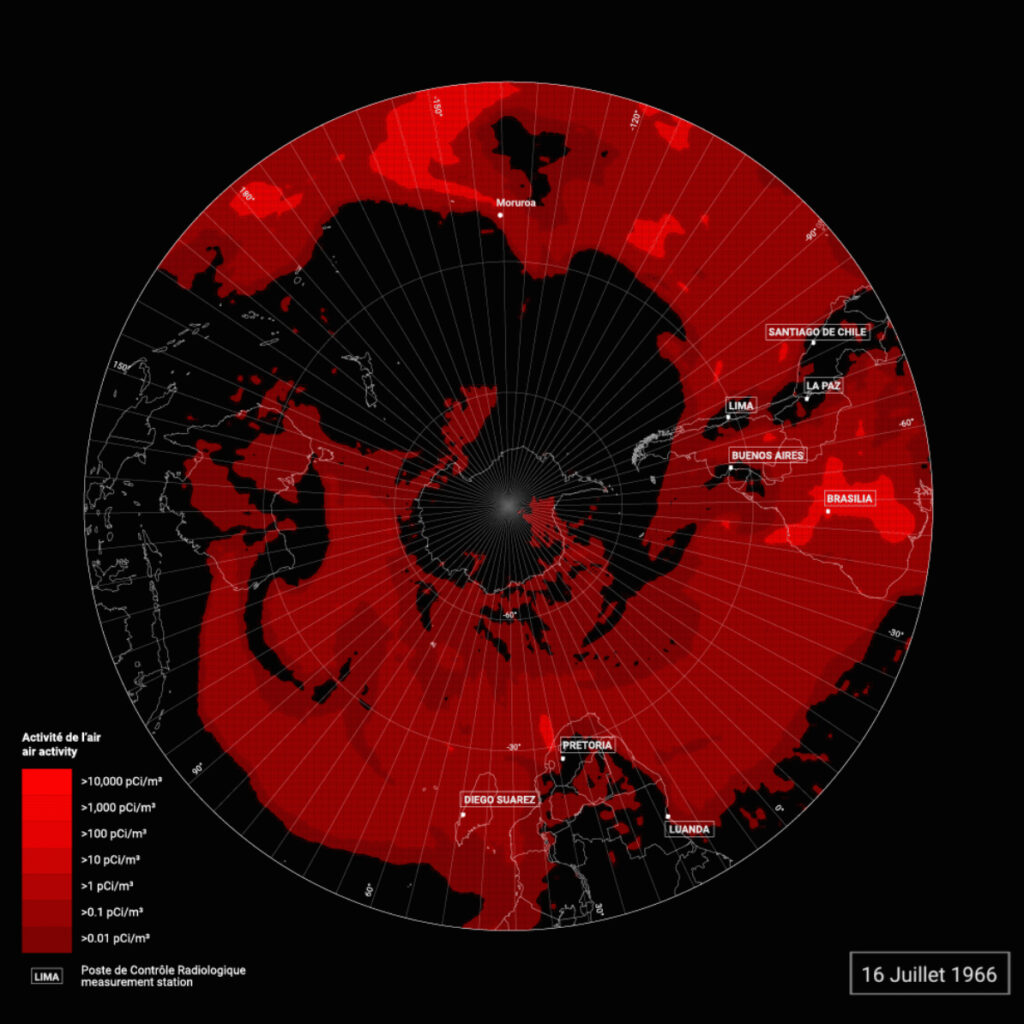

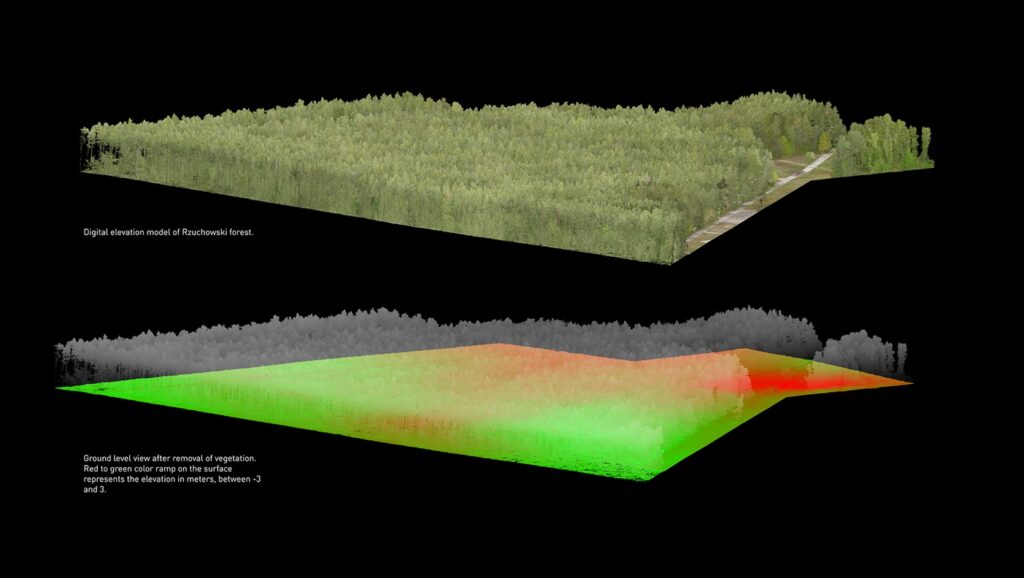

Over the past ten years, INTERPRT has collaborated with local NGOs and activists on a number of long-term artistic research projects that have focused on issues such as environmental crimes in West Papua, the impact of deep-sea mining in the Mediterranean, Shell’s oil spills in the Niger Delta, and most recently the illegal exploitation of the Brazilian rainforest in the Amazon. And while it might seem improbable, the aesthetic disciplines can in fact play a crucial role in such struggles. Because in the case of INTERPRT, aesthetics is not just about taste and making something visually appealing, but rather about making things perceptible, about the ways certain objects, materials and people represent the outside world. “The kind of challenges we face when representing things that aren’t easy to visualise mean that we have to work with a range of techniques, such as 3D modelling, satellite imagery and so-called ‘remote sensing’,” says Nabil. “It isn’t easy to paint a cloud or fog over a city, as every landscape painter knows. Both clouds and fog are highly material things, but they can be difficult to capture in an aesthetic form. They can be lethal or used as an alibi or a weapon. As visual artists, we have trained our senses and our ability to give form to such material phenomena and we can also deploy tools from the world of architecture, such as measuring instruments, to form an impression of the circumstances and to create a story around them. So our work is very much about collecting data and following facts, but facts on their own have no power; they have to be transformed into a narrative. Which means we have to create stories – stories about people and places, and about the violence that is committed.”

Despite the resistance to artistic research and the misunderstandings that surround it, most of which remain internal to the art world, it would appear that academia has begun to recognise the major potential of involving art in the practice of research. One indication of this is last year’s decision by the Research Council of Norway to support INTERPRT’s four-year Climate Rights project with a grant of 8.9 million kroner. This is apparently the first time that research funding has been given to a project at an art academy in Norway, and for Nabil, it represents not just a huge honour, but also a welcome opportunity to shift the debate away from the question of what art is and is not, and to focus instead on some of the major challenges our planet is now facing and on how art can help to solve them. One of the central aims of INTERPRT’s four-year research project is the further development of artistic methods that use visual culture in the pursuit of justice and of holding people accountable for abuses against nature and indigenous peoples. Just as the world itself is forever changing, so too – fortunately – are art and the methods of research. Projects like Climate Rights can help to show the need for us to expand our conception of art as an autonomous space for the pursuit of individualistic forms of “free” and “original” expression – which cater to a closed and elitist consumer market – and to begin to collaborate more widely than is generally the case today, in order to create alliances between social movements, academic environments and a creativity that fosters the changes we need. “When it comes to analysing and understanding how society is organised and imagining how it could be different, what could be better than a collaboration between artists and activists? For us, it is a question not just of gathering counter-evidence, but also of creating new fantasies, without which there is no hope,” Nabil concludes.

Article photo: Shell In Niger Delta. 3D Modelling, Geolocation, Remote Sensing. Photo: INTERPRT

This article is part of a new series on artistic research. For more details, see: Artistic research under the microscope!

Original text translated by Peter Cripps / The Wordwrights