The Aesthetics of Research

Reviews, Eline Bjerkan 26.09.2022

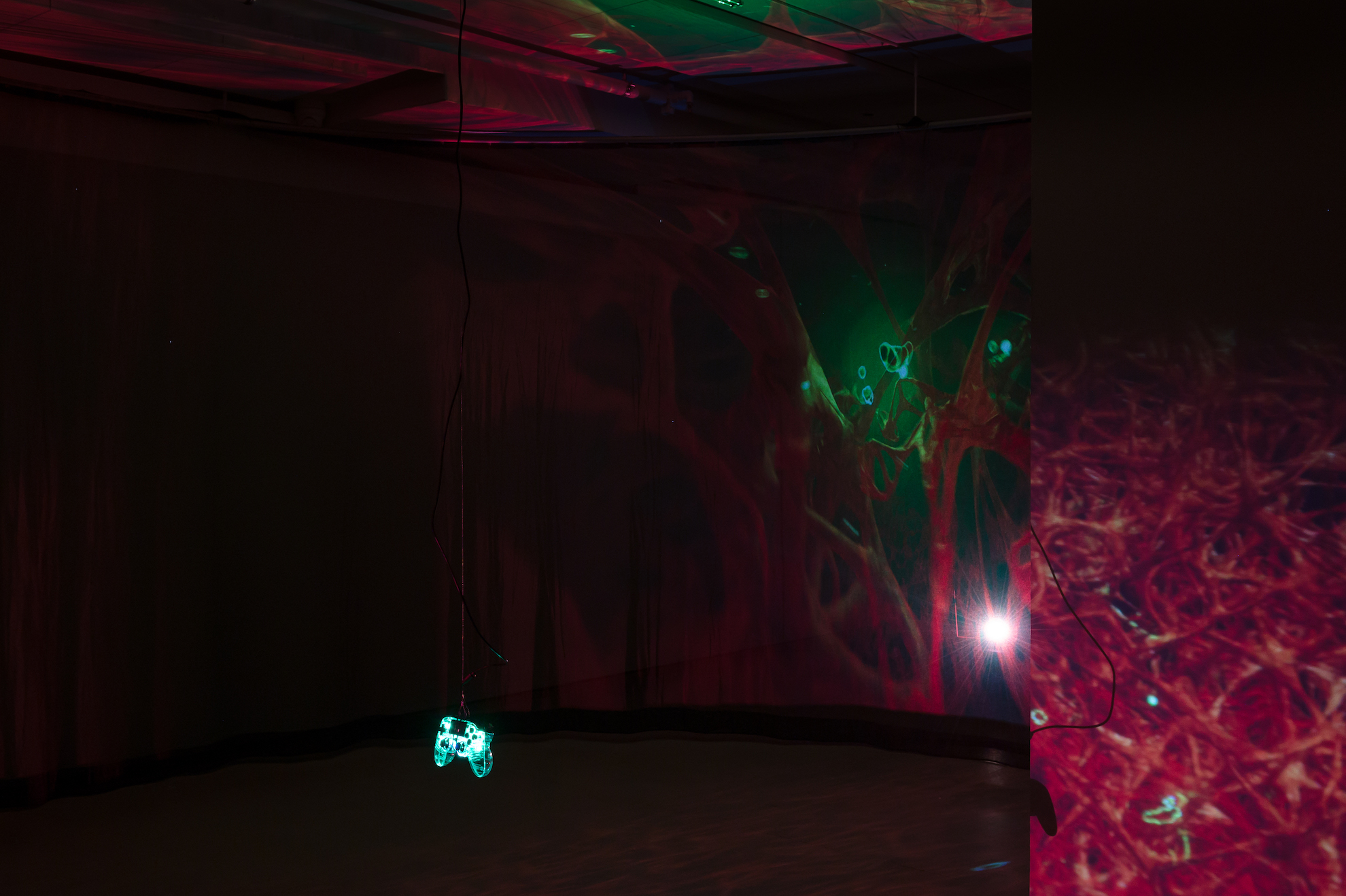

Aha – a computer game! I spent a while reverently walking in circles around a game console hanging from the ceiling in Susanne M. Winterling’s exhibition A threshold game of proximity, cluster and heat at Kunsthall Trondheim, before realising that the thing was there to be used. The situation could have been a scene from the celebrated satire The Square, a film that does its best to tear down the partitions we insert between art and everyday life. The fact that art spreads into other fields and genres – whether it be entertainment, fashion or research – is a theme shared by both exhibitions currently showing at Kunsthall Trondheim.

Before arriving at Winterling’s work in the basement, the visitor encounters Capture, an exhibition by the artist collective Metahaven. The wall- and screen-based works in the latter make the space feel somewhat empty and flat. One wall is covered with old track-suit tops, thin plastic bags, and textiles. Geometric motifs and vibrant colours are a recurrent feature, whether embroidered in thread on the bags and jackets or in separately woven tapestries. Circles, crosses and diagrams form futuristic landscapes that wouldn’t be out of place on the cover of a 1970s sci-fi novel. In addition to the focus on visual culture and design, there is also an element of anti-aesthetic: plastic bags are almost synonymous with rubbish, whereas the jackets could readily be described as tacky. The theme of plastic is continued in textile form in the glossy jackets and fabrics. The latter are made from “Lurex”, a synthetic yarn that was named to echo the English word “lure”. In a sense, the work invites us to indulge in illusions, to reflect on the relationship between high and low culture, although today this hardly represents an innovative position.

Metahaven’s exhibition also includes two extravagant video works. Chaos Theory (2021) consists of clips whose interconnections can be somewhat difficult to grasp. There are several lingering shots of a landscape with trees and bushes in front of electrical pylons, or of school pupils running from a school building, or of a girl playing a clapping game with someone who might be her mother. The mood is gloomy, with sombre colours and an accompaniment of mournful piano music. Motley scraps of information create the impression of a narrative about the relationship between a parent and a child who has disappeared. In addition to the voices of several narrators speaking different languages, there are subtitles that sometimes seem obscure or pretentious, such as the confection “the inexplicable abyss of you”. According to the catalogue, the video is making a point about the limited ability of language to describe reality. A theme of perennial relevance, and in this case the approach seems to be to fill the work with clichés, whether in the form of linguistic flourishes, shots of a glass shattering on the floor, or bombastic musical accompaniment. Yet these elements are given so little to relate to that the video itself comes across as a cliché.

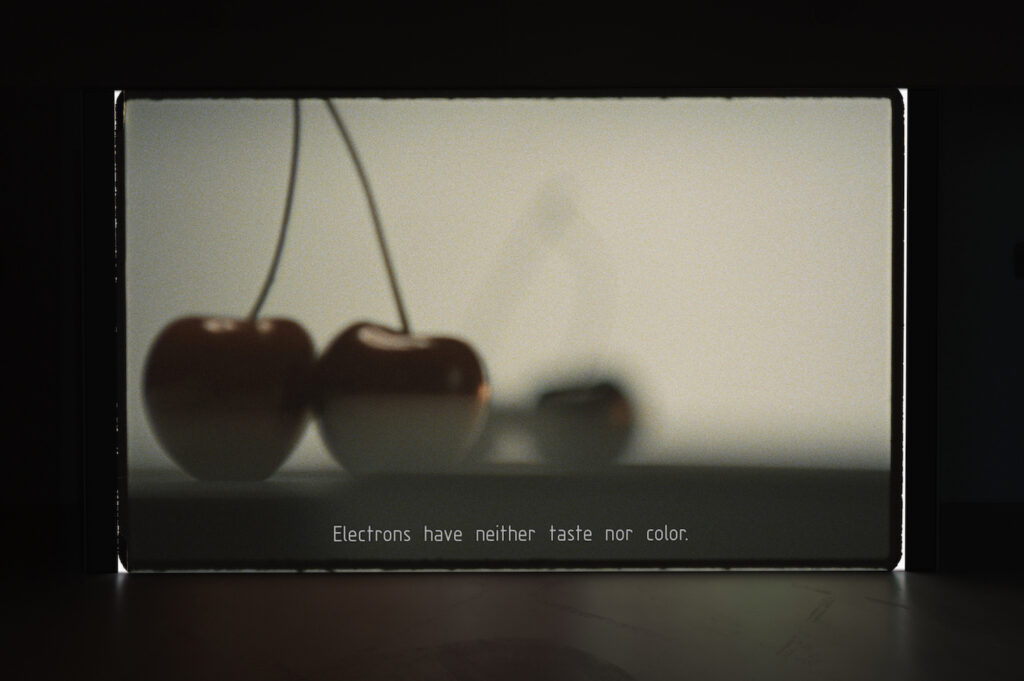

The second video work, Capture (2022), was specially commissioned by, among others, Kunsthall Trondheim and Arts at CERN. The influence of the latter is clearly apparent in the video’s storyline, which seems to revolve around a particle accelerator, electrons and protons, and a kind of dystopian scenario involving people who lose sight of each other, as they did in Chaos Theory. There are abrupt shifts between natural landscapes, such as a small wood outside Trondheim, and archival film material about the research facilities at CERN. In addition, there are sequences with close-ups of a woman’s face, a first-person narrator, and clips of nocturnal animals and insects. The content of the video seems disparate, making it difficult at times to grasp the role of particle physics in the fictional detective story about the woman, which involves the mention of both disappearances and wiretappings. In other respects, the video has the feel of a nature documentary, with a heavy focus on lichens and their symbiotic properties. One recurring theme seems to be the uncertainty and inconstancy of reality. But this tends to be overshadowed by the apparent aim to showcase, among other things, CERN as a research centre in its own right.

The scientific perspective continues in Winterling’s exhibition in the basement. Formerly a professor at the Academy of Arts in Trondheim, Winterling is currently teaching at the Academy of Fine Art in Oslo. Here the room is permeated by a purple light which, to my understanding, alludes to the colour of dinoflagellates, microalgae that the artist has researched. When large blooms of these algae occur, their surroundings take on a reddish colour, which can be viewed, so to speak, as a sign of ecological imbalance.

Another dominant element in the room is a table with an irregularly shaped surface of MDF and legs covered in brown tape at either end. The table is meant to resemble a turtle, whose head, likewise indicated by a bundle of tape, protrudes from beneath the flat table top. The work is a tribute to the giant cosmic turtle of Hindu mythology that carries the world on its back. Winterling’s table top traces the shape of a desert area between India and Pakistan. Arranged on the table are a number of small organic objects including seeds, wood fragments, and a feather in a glass container. There is also a screen showing a computer-animated camel’s snout in impressive detail. These elements establish connections between the mythology, geography, and ecosystem of the region. It is unclear why the artist has chosen this particular area, apart from the fact that it is warm there, and warmth appears to be a leitmotif in Winterling’s work. With its rather makeshift appearance, the table as a whole stands in stark contrast to the technological finesse behind the screen with the camel’s snout.

Hanging on one wall in the same room are four photographs. Two of them, which show horses in a lush, green landscape, look rather similar. Differences in the sharpness of focus and the fact that they bring us close to the horses and the seemingly pristine nature give the pictures a romantic touch. The other two photographs are more like snapshots; in terms of composition they seem arbitrary, the light is harsher, and the full extent of each scene is in sharp focus, with the result that they tend to lack depth. Here as well, a horse is featured, although this time it appears to be tethered to a plastic bucket in a setting that clearly shows the impact of human activity. Animals are a recurrent theme in the exhibition, and here they serve to address the relationship between the human use of domesticated animals and animals as possessing inherent value.

Finally, I find myself in the room with the games console described at the outset. Here the heat has been turned up a notch, and projected onto the floor, ceiling, and textiles are patterns that look like dense lattices of blood vessels. The light and heat create an immersive, captivating atmosphere. The computer game involves guiding a bacterium that carries a medicine capable of curing diseased cells. Apparently, this scenario is based on genuine biomedical research, in which bacteria, stimulated by differences in temperature, can be used to administer medicine to the body. But when I try my hand at the game I don’t succeed in healing anything. I can’t figure out the control system and it isn’t clear what I’m supposed to do. Neither does the idea behind the game strike me as very engaging in this context.

Both the Winterling and the Metahaven exhibitions seem heavily indebted to research and the accompanying catalogues are loaded with reference-rich and sometimes rambling texts. Especially in the case of Winterling’s show, without the information in the catalogue key aspects of the works would have remained opaque. Assisted by the catalogue, some vague connections appear between the aspects of heat, geography, and pathological representations. The subject of global warming immediately comes to mind, but heat is also presented here as a healing force. Both exhibitions seem somewhat infatuated with the research on which they are based. Ideally this ought to serve as a background material for the creative artistic process, but in many respects I find the aspects of aesthetics, craftsmanship, or communication of the ideas are left wanting. The result is an idiom that sometimes seems sloppy and reduces the content to being merely illustrative. Or which, alternatively, obliges you to get reading in order to read meaning into the work.

Metahaven

Capture

Susanne M. Winterling

A threshold-game of proximity, cluster and heat

Kunsthall Trondheim

07.09.–13.11.2022

Original text translated by Peter Cripps / The Wordwrights