Whatever Becomes (of) Us

Reviews, Eline Bjerkan 13.06.2022

This year’s edition of the art and technology biennial Meta.Morf has the title Ecophilia, a term that denotes to the human need for contact with nature. This is both a pressing and a timely theme, if not entirely new. It reflects an eco-philosophical trend in the art field, one that has been championed not least by Kunsthall Trondheim, for example in its group exhibitions Et nytt vi (A New We) in 2017 and this year’s Sex Ecologies. Last year’s festival exhibition, Jeg er mangfoldig (I Am Diverse), which was shown during the Arctic Arts Festival in North Norway, addressed the same theme.

Ecophilia is spread across a number of venues in Trondheim, with group exhibitions in which artists seek to understand or even transform themselves into other creatures. The results that I encounter at Kjøpmannsgata Ung Kunst (K-U-K) are somewhat mixed. This is where one of the biennial’s most compelling works is to be found – a twenty-channel sound installation by Frank Ekeberg that immerses the visitor in the twittering, creaking, and humming of a primeval Norwegian forest. The location invoked by Ekeberg’s Ingenmannsland (No Man’s Land) is nothing less than a coastal rainforest in Western Norway, where the artist made several field recordings. Initially, the airy space is filled with teeming life, but gradually the noise begins to die away. The entire work lasts for many hours, during the course of which some eighty percent of the sounds disappear. This represents the percentage of species that have become extinct since humans first walked the earth, but also the amount of Norway’s temperate rainforest that has been destroyed over the past 100 years. Towards the end, the species that have fallen silent are replaced with artificial sounds, the artist’s idea of what might be heard in the future. Few people will listen to the work in its entirety, but during the minutes I myself spent in the space, I noticed a clear development from a rich and present soundscape to longer intervals of troubling emptiness.

The differences between Ekeberg’s installation and the other works exhibited at K-U-K are considerable. Most striking is the allocation of space. Whereas Ingenmannsland is given a large hall all to itself, the rest of the art is huddled together in a smaller, neighbouring room. The other works are screen-based and are far less sensual and direct in their appeal than the sound installation. Jatun Risba’s use of excessive sensuality could be seen as an attempt to compensate for the flatness of the video format. Her video work Be-coming Tree consists of footage from a Slovenian forest, where the artist is seen lying stretched out naked on a tree trunk. The same setting is pictured from different angles, as the surrounding forest changes character with the passing seasons. As the title suggests, there is a reference here to entanglement between man and nature, an entanglement of an embryonic kind, according to the catalogue. It’s a neat idea, but as a viewer, one finds it hard to grasp what’s going on beyond the fact that one sees an (attractive) female body decoratively posed in a peaceful forest glade. If anything, there is something comical about the figure lying there with her face pressed into the bark while everything around her changes. In this sense, the work is best viewed as a kind of ironic commentary on contemporary attitudes.

While Risba waits to merge with her tree trunk, Annie Hägg has created a work inspired by video games, in which the central protagonist strives, among other things, to “hide in a dog’s body”. This, she believes, will bring her happiness. The work is also about caring for the environment, insofar as the character is trapped inside a game landscape where she maintains her “lives” at a sustainable level by continuously picking up litter in a park. For most of the video we watch this figure running around in a virtual reality while she tells us about things like her litter-picking tool, which makes the task of picking up rubbish so much easier. From the catalogue text we learn that the artist wants to draw lines between paid labour, escapism, society, and nature. Despite a number of interesting observations, I am not convinced the work presents them in a form that is clear and captivating. It would probably have been more engaging if it involved an interactive element in line with its video-game aesthetic.

Rather more interesting is Thomas Thwaites’ GoatMan. For this project, the designer constructed for himself a costume that mimics a goat’s body and devoted himself to actually living like the animal. At Trøndelag Centre for Contemporary Art, this costume is suspended from the ceiling. It consists of a helmet, upper-body support, and prosthetic legs that end in hoof-like extremities. The installation includes video documentation and selected photographs of Thwaites in his animal guise among a herd of goats. The Norwegian edition of his book GoatMan, which was published after the project, is displayed on a plinth. All this is thoroughly intriguing, but what makes the project significant is the artist’s depth of commitment and reflection. This becomes evident in the book, where he describes the shamanistic practices of various cultures that people have used to get closer to animals. He also offers insights into evolutionary similarities between humans and other animals, as well as fascinating details of how to make an artificial rumen to break down grass so that it becomes digestible for a human. Unfortunately, this is not reflected in the material displayed at the Art Centre, where the body suit and the documentation function more as isolated points of reference. Instead of exploring Thwaite’s work in depth, the documentary video devotes too much time to clips of news anchors making derisive remarks about the nutter who wants to become a goat. The result is a failure to convey the profounder aspects of the project.

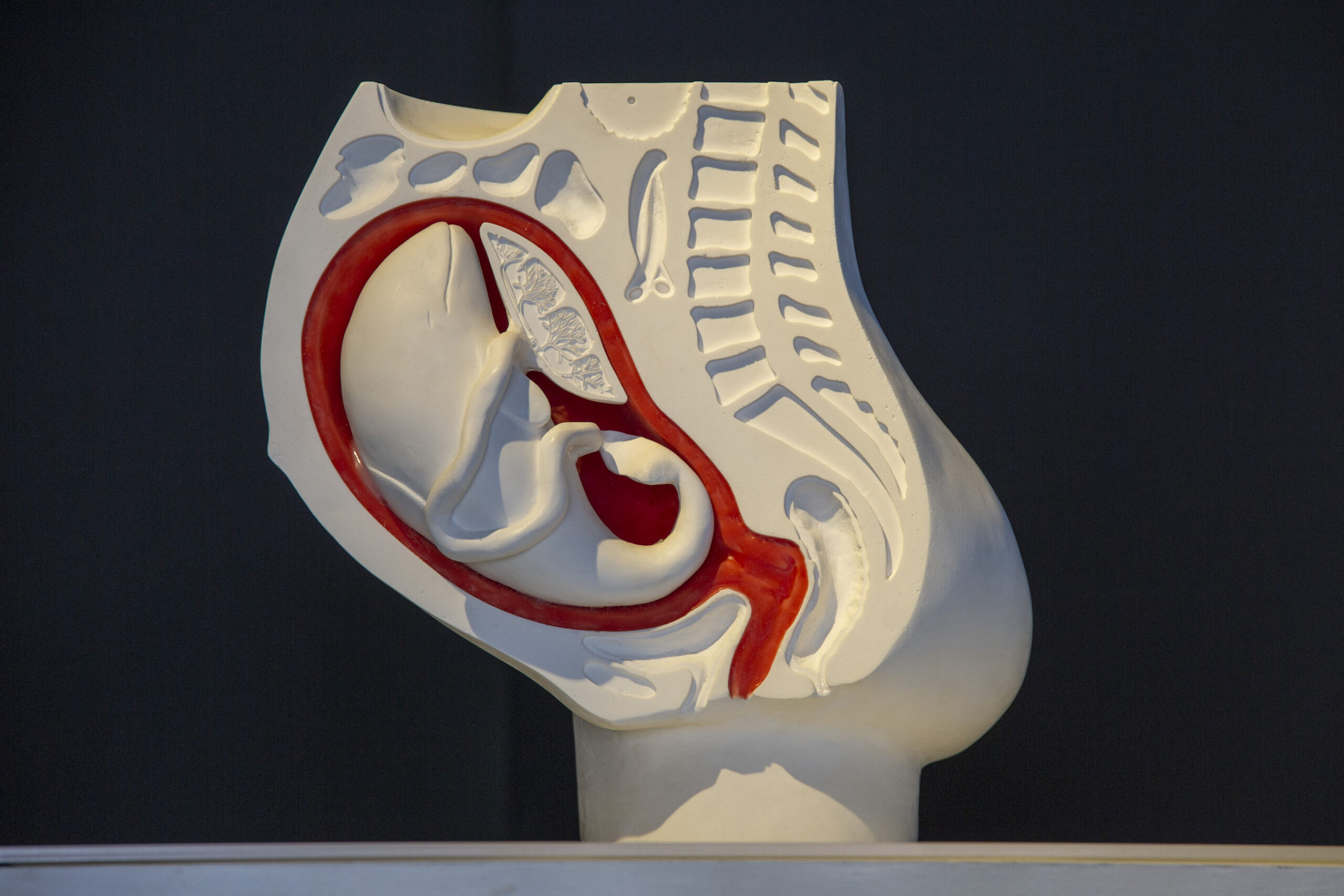

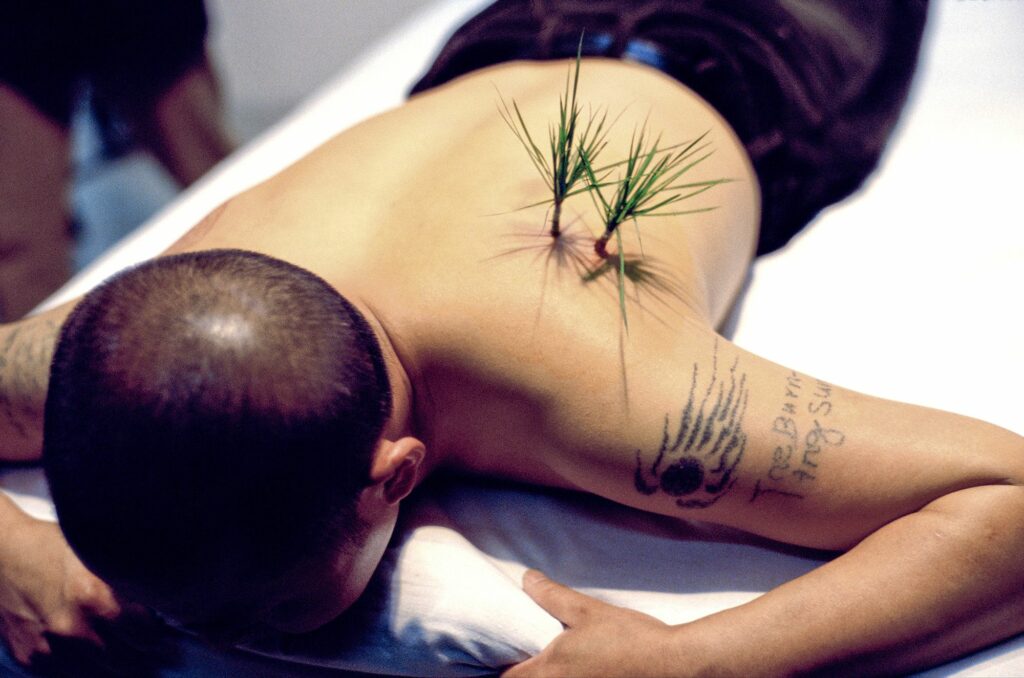

But this is not the only radical idea in the exhibition. Another example is the installation by Ai Hasegawa, which plays with the idea that a woman could give birth to an animal of another species, in this case a dolphin. Might this be a way to curb human overpopulation while simultaneously promoting biodiversity? The proposal is controversial to just the right degree, and Hasegawa’s art is best when it illustrates her thoughts in a scientific fashion. Here the anatomical models allow us to maintain a decorous distance from the subject matter. That distance shrinks considerably in the video that runs nearby, which appears to show a baby dolphin popping out of a woman’s vagina as she floats in a pool. Another artist who takes a drastic approach is Yang Zhichao. During a performance in 2000, he engaged a surgeon to make an incision into his shoulder and to “plant” grass inside the wound. On show in the Art Centre is a video documentation of this operation.

A rather more hard-headed presentation about the Anthropocene is provided by Maria Roszkowska and Nicolas Maigret. The duo have created a so-called bestiary: boards with illustrations and descriptions that cover an entire wall inside the Art Centre. In black-and-white text and images, they describe phenomena such as “plastiglomerate” (rock that consists in part of plastic and other rubbish), eagles trained to attack drones, and the military robotic dog called BigDog. While many visitors will probably already be aware of at least some of these, it makes a powerful impression to see them listed together. The work comes across as a succinct and representative portrait of our contemporary era.

The same artists are also represented with the work Life Support System, which has been set up at Trondheim Electronic Arts Centre (TEKS). Here the walls of the small showroom are lined with a kind of silver foil, while the windows are covered in a purple-coloured foil. This creates the impression of a laboratory. Standing in the middle is a one-square-metre platform covered in wheat plants, which are irrigated from a large container nearby. Suspended above the wheat is a light source and a couple of electric fans. The installation presupposes a scenario in which we have to grow our food in closed, artificial environments, as opposed to outdoors in cultivated fields. The implications are enormous: the artists estimate that the cost of growing wheat in this way would raise the price of flour to 200 Euros per kilo. To put this into perspective, half a kilo of flour is what it takes to meet a single person’s daily need for calories. Half a kilo of flour is exactly what the single square metre in the TEKS installation could produce. Yet some of the plants have already withered; it is proving difficult to maintain the correct humidity. A TV screen in the room updates the visitor about the state of similar experiments currently underway in other cities around the world.

Although rather illustrative, the wheat installation is one of the works that show this year’s Meta.Morf at its best. What these works have in common is a rigorous, unsentimental approach to the ecology theme. By and large, they also avoid the temptations of sensationalism, unlike Zhichao’s grass implantation, which is presented without any insights into the artist’s motivation or the project’s implications. Rather than passively yearning for something other than human existence, which is what one imagines the artist behind Be-coming Tree is doing, Ekeberg, Roszkowska, and Maigret all take an active stance on contemporary environmental challenges. The desire to identify more closely with the creatures around us is all very well, but we must not allow daydreams to obscure our human comprehension and responsibilities.

Meta.Morf 2022: Ecophilia

TEKS 07.05. – 31.07.2022

TSSK 19.05. – 31.07.2022

K-U-K 16.05. – 14.08.2022

Original text translated by Peter Cripps / The Wordwrights