Exile is a General Condition

Intervju, Martin Palmer 08.11.2016

Whatever singularity, which wants to appropriate belonging itself, its own being-in-language, and thus rejects all identity and every condition of belonging, is the principal enemy of the State. Wherever these singularities peacefully demonstrate their being in common there will be Tiananmen, and, sooner or later, the tanks will appear – Giorgio Agamben, The Coming Community

Claire Fontaine, an internationally recognized «collective artist», refers to herself in the singular, and self-describes as a readymade subjectivity, or readymade artist, operating within the context of a politically impotent contemporary society.

Claire Fontaine, an internationally recognized «collective artist», refers to herself in the singular, and self-describes as a readymade subjectivity, or readymade artist, operating within the context of a politically impotent contemporary society.

Her art is being produced by self-proclaimed assistants concerned with analysing our current crisis of individuality. Martin Palmer met the assistants on the occasion of the exhibition this is a political (painting) at Kunsthall Trondheim.

Can you briefly introduce yourselves and your respective backgrounds, and how you started working together?

This is a personal question that we find distractive, as the device of Claire Fontaine has been created precisely to bring the attention away from misleading biographic details. There are no secrets about us but we prefer to focus on Claire Fontaine rather than our personal lives. We met in Paris and Claire Fontaine began in 2004, our first exhibition took place in January 2005, in Berlin. We were invited to make a solo show, by Josef Strau at Meerrettich, an artist run space that no longer exists.

Who or what is Claire Fontaine? You are described as a collective, but refer to this name in the singular as an artist, and yourselves as her assistants. Why?

Claire Fontaine is a space of  desubjectivization, which means that it is a space of freedom from ourselves, from the constraining coherence with our identities and the necessity of mirroring ourselves in our productions. It is a space of experimentation aiming to create a practice of freedom, so it is at the same time singular and collective. We have built this device to shift the focus from the sovereign demiurgic figure of the artist to the actual creators and producers of the artworks, the assistants. The idea of the assistant comes from Agamben’s text entitled The Assistants that traces a genealogy of this figure underlining his messianic redemptive power.

desubjectivization, which means that it is a space of freedom from ourselves, from the constraining coherence with our identities and the necessity of mirroring ourselves in our productions. It is a space of experimentation aiming to create a practice of freedom, so it is at the same time singular and collective. We have built this device to shift the focus from the sovereign demiurgic figure of the artist to the actual creators and producers of the artworks, the assistants. The idea of the assistant comes from Agamben’s text entitled The Assistants that traces a genealogy of this figure underlining his messianic redemptive power.

How does it affect the way you approach your work to produce it within the parameters of a conceptual personality, as assistants for what you’ve called a readymade subjectivity?

It affects it positively, Claire Fontaine is, as we previously stated, a very liberating device that allows us to do things that would be impossible within the framework of an individual art practice. We have spoken about the phenomenon of the ready-made artist but this concept tends to be misunderstood or moralized, as if the loss of individuality meant an impoverishment. As the ready-made within the history of sculpture is a moment of immense freedom, expansion, enlightening, the ready-made within the field of subjectivity should also be perceived as a victory against pernicious romantic mythologies related to artists’ personality and their supposed exceptionality.

In an earlier interview, you have said that the readymade artist is the ordinary condition of anyone producing art today. Can you elaborate on that?

Political and social avant-gardes have always insisted on the fact that everyone can be an artist. Now capitalism has made this possible, through a massive diffusion of devices that allow everyone of their owners to produce, modify and share images. The population that has access to these commodities is somehow highly visually educated and evolves in complex and rich visual environments, it assimilates an immense amount of visual and written information; studying visual art is indeed not remotely the same journey that it used to be twenty or even ten years ago.

With the concept of the ready-made artist we were analyzing the mass production of artists, and not only the one of objects – that the ready-made was born of as a gesture, a response, a position taken by the artist (the term ‘ready-made’ is closely related in Duchamp with ‘prêt-à-porter’, the industrial production).

The whateverness we are pointing at isn’t a lack value, it is on the contrary the extraordinary value that overthrows the problematic category of value itself, and shows how it is completely polluted by its monetary meaning. The ready-made is definitely a space where the category of value is put into a crisis and faced with its paradoxes.

What can you tell me about the work you are exhibiting at Kunsthall Trondheim?

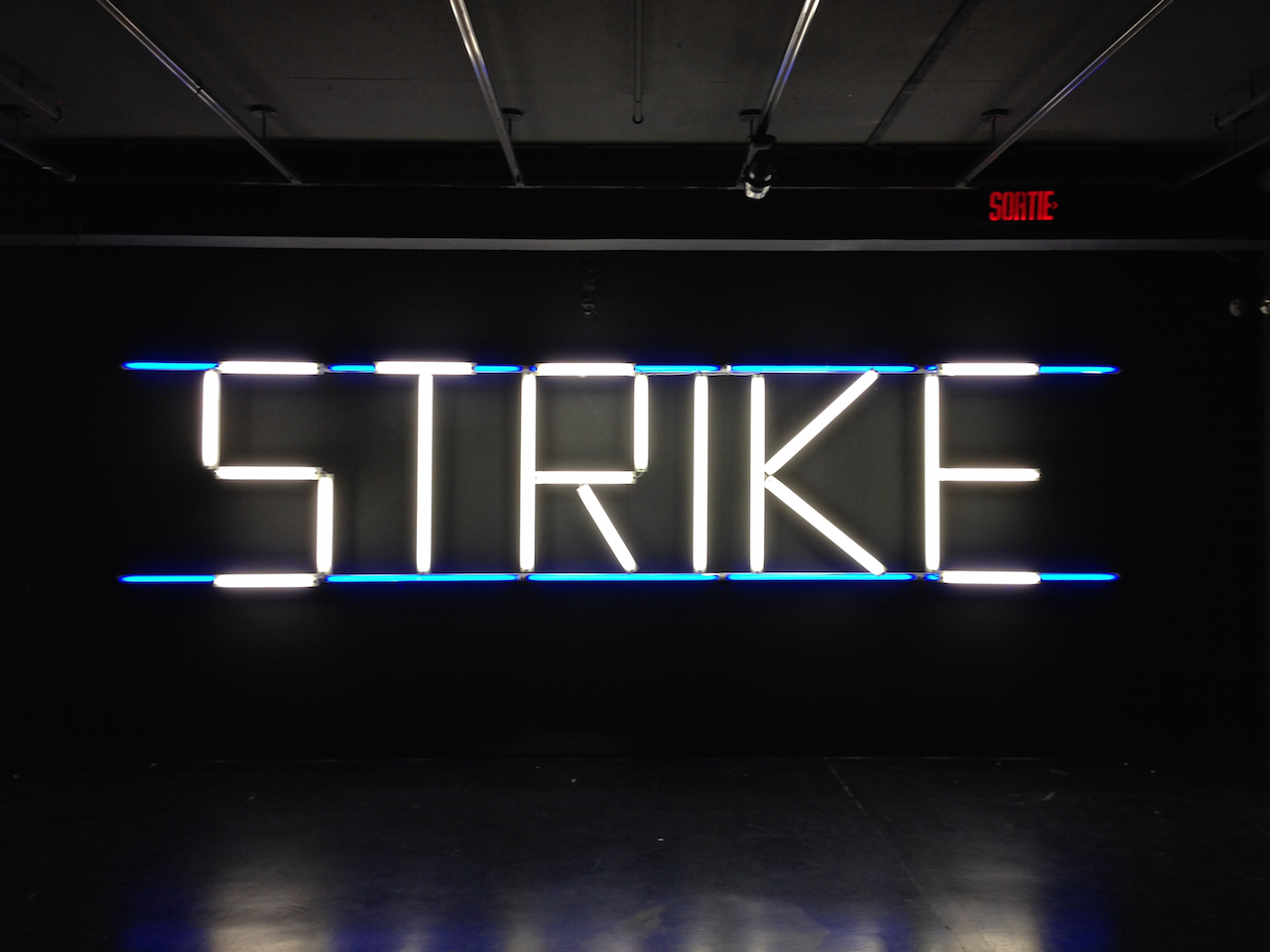

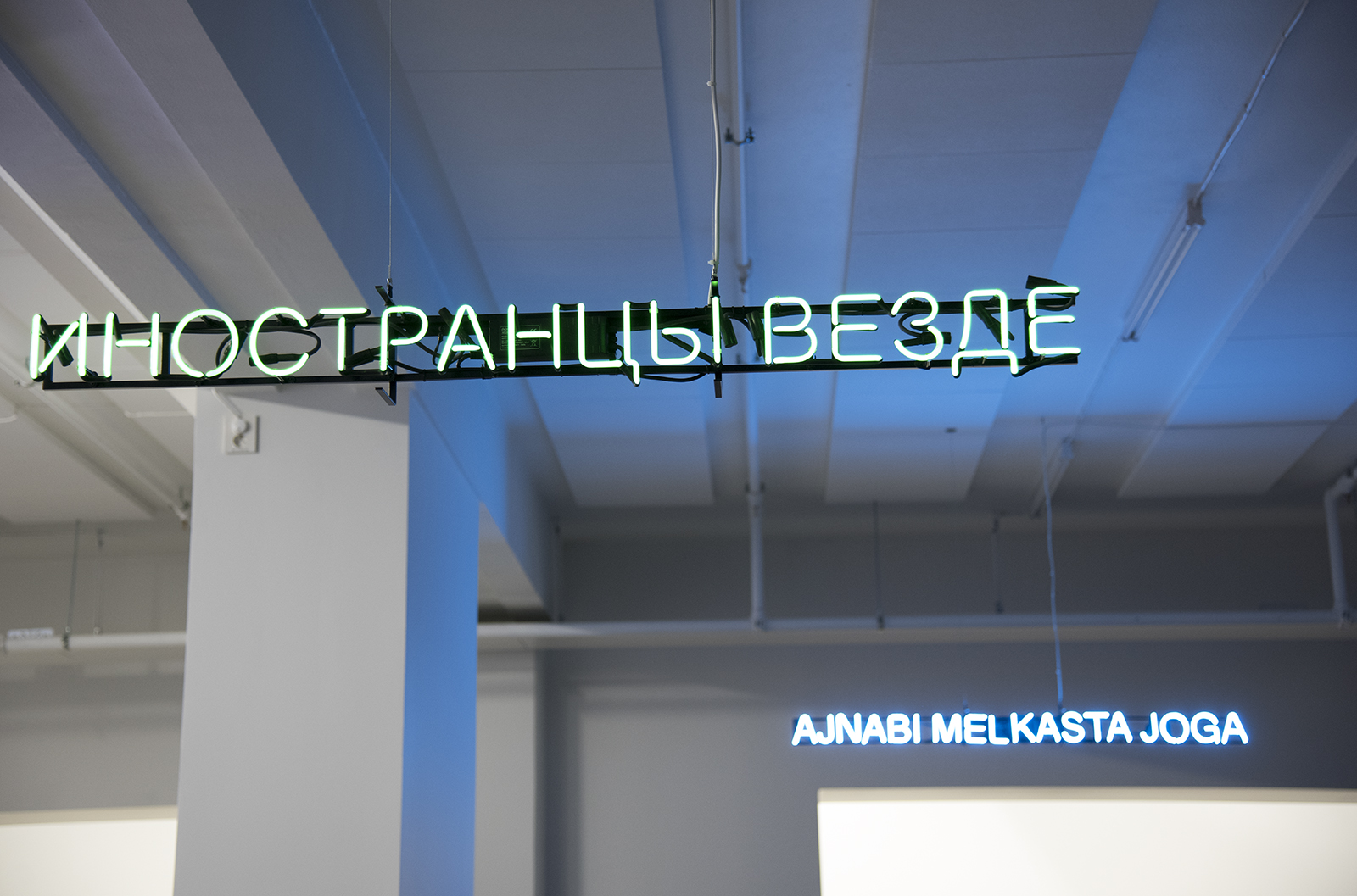

For the opening of Kunsthall  Trondheim we have created a group of fifteen neon signs from the series Foreigners Everywhere. They translate in the fifteen most spoken languages in the geographic area of Trondheim the two words ‘foreigners’ and ‘everywhere’; for the languages not spoken by us the translations have been established through a dialogue with linguists and researchers, in order to preserve the ambiguity of the sentence.

Trondheim we have created a group of fifteen neon signs from the series Foreigners Everywhere. They translate in the fifteen most spoken languages in the geographic area of Trondheim the two words ‘foreigners’ and ‘everywhere’; for the languages not spoken by us the translations have been established through a dialogue with linguists and researchers, in order to preserve the ambiguity of the sentence.

The signs stress, in fact, that we can feel like foreigners wherever we go, but also that today more than ever we will find foreigners in every place, and in this instance they provide us with a map of the immigrant communities of the area. The series of neon signs Foreigners Everywhere in various languages is conceived as a work that establishes with its environment a sort of symbiosis. These neon signs – exactly like foreigners, like displaced people – don’t have a place of their own: the ambivalence of their meaning reacts with the different sites and contexts where they are placed.

The work also suggests that immigration and emigration are no longer simple epiphenomena linked to the economy but they are existential and perceptual experiences in their own right. The strangeness that we can all feel, when faced with a world entirely fabricated and governed by logics that are not always understandable, unites natives and immigrants of our time, it makes exile a generalized condition.

The use of different languages also questions the violence implicitly contained in every translation and the necessity of the foreigner to submit a language to another in order to be more widely understood while being more deeply culturally colonized. The contradictions and the power relations that one’s own language buries or blunts become manifest when one uses a language that isn’t one’s own. The struggle with meaning can then give form to what Deleuze and Guattari claimed to find in Kafka’s writings: «a foreign language within language».

Why neon signs? Is it an aesthetic choice or does it provide a subtext to the work?

Why neon signs? Is it an aesthetic choice or does it provide a subtext to the work?

To say it with Duchamp, the choice of neon is a non-aesthetic decision, neon is visually anonymous – it could be the work of any artist from the formal point of view. It is also somehow a utilitarian decision, the aim with luminous signage is to give life to words, to give them a tridimensional presence, transforming the surrounding space into a support, like commercial signage does. On the other hand when the operation is made with artworks, the words tend to function as a subtitle to the space, highlighting hidden tensions or problems.

Do you experience different reactions and/or interpretations of Foreigners Everywhere, depending on where you exhibit it?

Yes. At times very hostile reactions. In our first show at Reena Spaulings Fine Art in New York, we exhibited the sign Foreigners Everywhere (Arabic) in the vitrine, and the gallerist entered into a fight with neighbors, who were hostile to Arabic signage in their public space. The gallery was forced to put up a sign in the window with English translation. Unfortunately, this didn’t calm them, and Reena Spaulings´ lease wasn’t renewed. In other situations they have caused very heated discussions, the choice of a particular language for a context is always political and it has consequences.

Claire Fontaine is also a published author. What can you tell me about the written work in relation to her more tangible art?

Conceptual and literary researches are part of our practice as is the case for numerous other artists. This part of the work is neither the pursuit of the same problems with a different medium, nor a conceptual frame for the reception of the visual artworks. We conceive it as a separate exploration related to the rest, but not in an illustrative nor in an explanatory way. The relationship of the writings with the artworks is dialectical, at times linear, at others apparently contradictory.

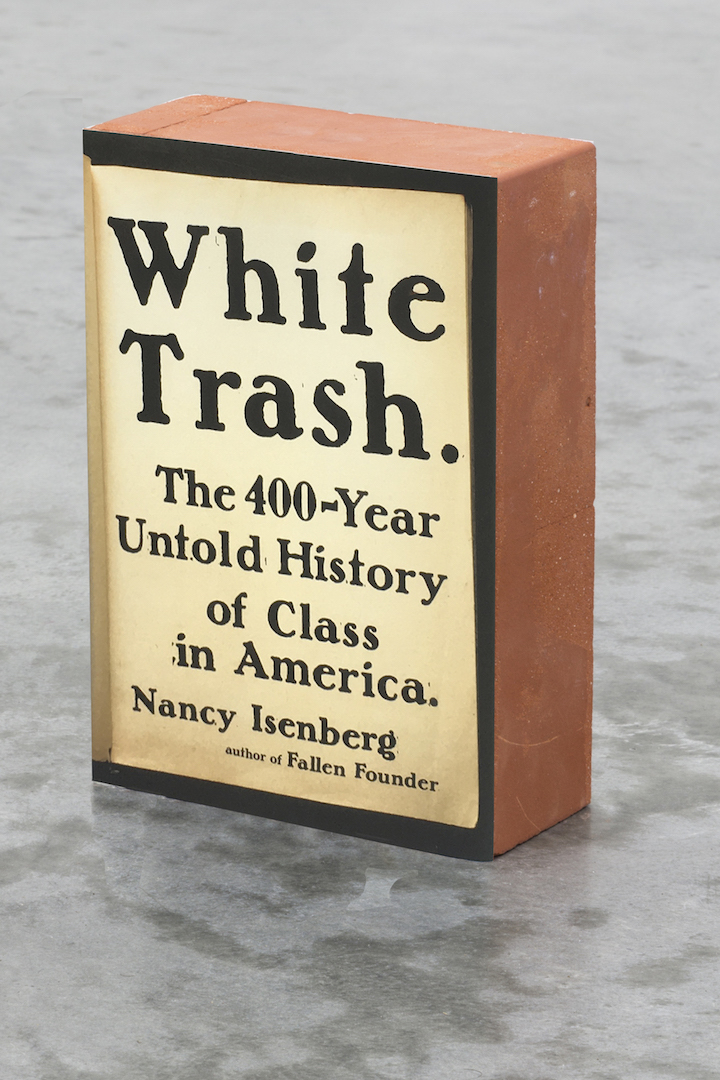

The term ‘human strike’ designates the most generic movement of revolt against any oppressive condition, it describes a more radical and less specific strike than a general strike or a wildcat strike as it takes place in the field of subjectivity.

Human strike attacks the economic, affective, sexual and emotional positions within which subjects are imprisoned. It provides an answer to the question “how do we become something other than what we are?” It isn’t a social movement although within the uprisings and agitations it can find a fertile ground upon which to develop and grow, sometimes even against them. History is full of examples of human strike, it would be great one day to track them systematically.

Is Claire Fontaine a revolutionary?

Revolutionary isn’t a self-declared condition, it isn’t up to us to decide.

As assistants, do you ever have the need to produce personal work that lies outside Claire Fontaine’s vision? Is it even possible at this point?

The advantage of the device of Claire Fontaine is that it allows and multiplies freedom. There isn’t a precise path that the work must stick to, the device has never been discussed in such ways, the desire to make work outside of it might mean that it has become insufficient or non-effective and this isn’t the case for the moment.

Do you feel that Claire Fontaine succeeds in dissolving your own identities, or does her attempt at a «whatever singularity» tend to increase the interest in who the people behind the moniker is?

The aim of Claire Fontaine as a device isn’t to dissolve our identities nor to make people curious about them, it is a way to introduce us and the public to something else, more pleasant, spacious and interesting than our own subjectivities. That’s how we present the project to people: there isn’t any sacrifice of a supposed individual and singular practice that would get diluted or altered inside a shared space, there is instead the joy of making possible things that wouldn’t be possible if we worked separately. Collectivity is a multiplication of forces and freedom, not a compromise or an obligation.

What lies ahead for Claire Fontaine?

Hopefully a future, as long as the destruction of the planet allows it to be.

Norwegian version; Eksil er en allmenn tilstand.

this is a political (painting) at Kunsthall Trondheim are on display until february 26th 2017.

Pictures from the exhibition.