Drawing helps drawing you in

Interviews, Intervju, Märit Aronsson-Towler 26.01.2024

–The underlying questions in all my books are: Why do we wage war, what can we learn from them, and can we ever forgive each other? How can we make sure there’s sustainable peace? War makes me so angry, and I think the anger is partly what is fuelling me.

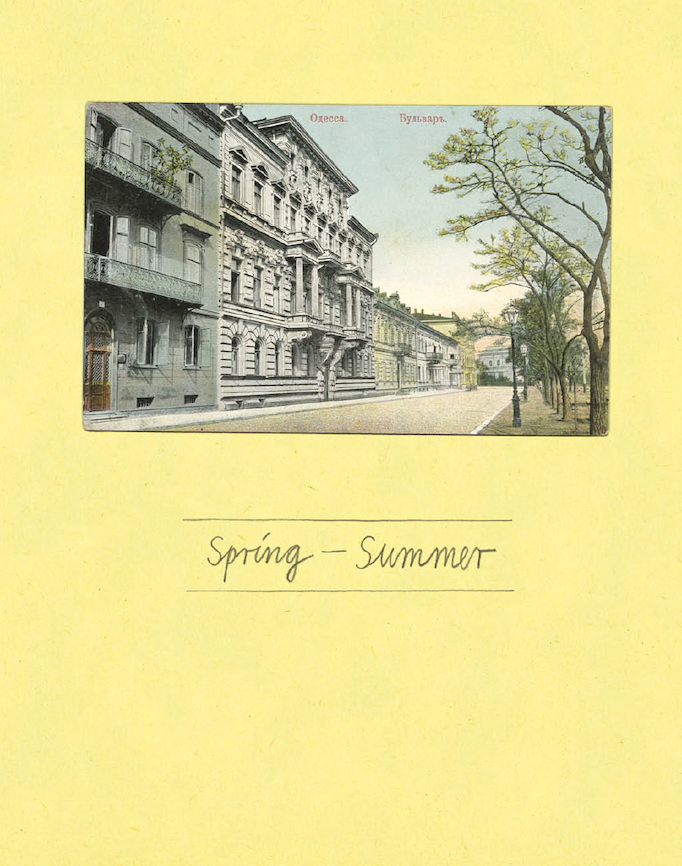

Nora Krug is a German-American illustrator and author. She had her international breakthrough five years ago with the book Heimat – a German Family Album, where she confronts her own family’s background during the Nazi regime. Her latest book Diaries of War, gives insight into the everyday experiences of a Russian artist and a Ukrainian journalist during the first year of the war in Ukraine. It was first published in the L. A. Times on a regular basis, and then collected in a book published a few months ago. Nora Krug is invited to Litteraturhuset in Trondheim the 4th of February to talk about her work. I had the pleasure of meeting up with her digitally, to speak about the power of drawing, the true meaning of patriotism and how to replace the word shame with responsibility.

Märit: Tell me about how you first got the idea for Diaries of War.

Nora: Well, I’m German but have been living in New York for 21 years now, and it was a very emotional experience for me to see the events in Ukraine unfold, watching from far away. I understood that this is not just a war between Russia and Ukraine, but that Russia’s new invasion has major consequences for all of Europe.

I don’t know what the sentiment is in Norway, but in Germany we seem to have lived in a naive peaceful bubble for a long time. What is considered the most terrible war of the 20th century had been initiated by us, and we believed it would never happen again. Seeing this new war from afar made me realize again that democracy isn’t to be taken for granted, and that it is something we need to defend. I think a lot of people in Germany had taken it for granted.

February 2022 was a very disturbing moment for me, and I felt that I needed to do something. But I’m not a politician or a soldier, I knew that I needed to use my own tools, and I thought about how I could raise money and awareness for Ukraine. I got the idea to create a dual diary representing two contrasting viewpoints from both Ukraine and Russia. I reached out to a handful of acquaintances in these countries, and soon I found two protagonists who supported the idea and with whom I started to work.

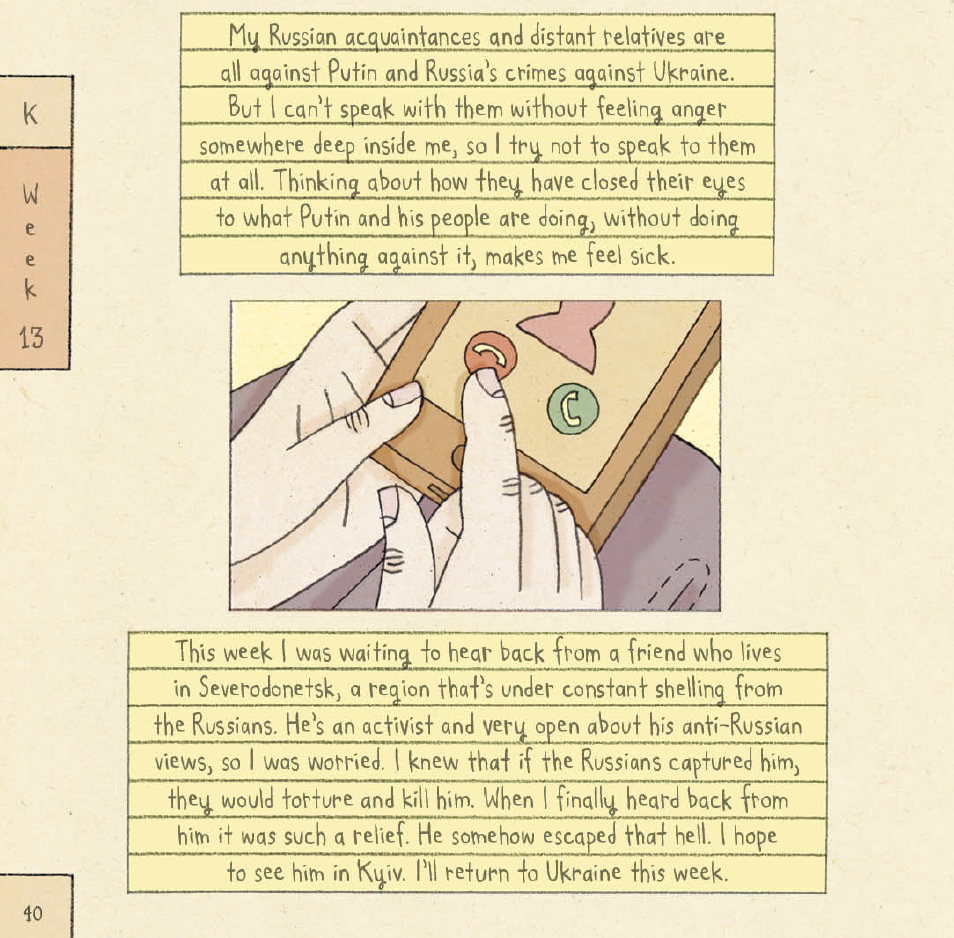

In the book, they are named K. and D., as a safety measure to ensure their anonymity. How has the weekly routine of being interviewed been for them?

They both told me that our meetings have helped them reflect more deeply on how the war has been affecting them. There was a closeness between us that developed over time, and a mutual trust. We shared the notion that if we didn’t write these things down now, we would eventually forget what the first year of the war felt like. So for them, the book represents a lasting document of their feelings and thoughts throughout that first year. I can only imagine how strange it must be for K. and D. to see the book in bookshops now, and to read their own voices!

Our conversations were very personal. I asked them what they dream about and what they were afraid of. Their replies were quite fragmentary and based on these answers I constructed a coherent text. I passed the text by them every week so they could approve of the content and also to assure we preserved their anonymity, before sending it on to my editor. At the moment, I’m working on an anniversary piece for the L.A. Times, in which I catch up with the interviewees, to see how and where they are now. It will be published at the end of February.

D., the Russian man, speaks openly against the war, and is eager to see Putin dead, which must be a dangerous stance. Can you say something about the safety measures you all have taken to be able to realize this book?

A project like this could cause problems for any of us, since it talks about Russia and its current government in a negative way. I changed a lot of details about D.’s life, and I made sure not to contact him on days when he returned to Russia, because I was worried that an airport official could check his phone and see my messages and his replies. And I always tried to use the safest technological platforms for our communication. For K., being a Ukrainian journalist reporting on the war, there’s always the danger of a Russian secret agent showing up on her door step. In addition, the Ukrainian secret service has become more and more scrutinizing towards Ukrainian journalists, because they want to control what’s in the media.

I was already known to certain Russian diplomatic representatives before I started the work with Diaries of War. When the On Tyranny came out, a book by the U.S. historian Timothy Snyder which I illustrated, I was approached by two Russian diplomats at one of my events in Germany. That book is also critical of Putin’s regime, and Timothy is persona non grata there. The day after Diaries of War came out, I had 1000 hacking attempts on my website.

Does the scrutiny of Putin’s regime encourage you to continue with similar projects, or does it make you more careful?

I’m not going to remain silent just because someone doesn’t like what I do. I’m not intimidated by this kind of thing – it makes me even more convinced that I need to do the work I’m doing. My work is political, but I’m not an investigative journalist, so I don’t think I’m a prime target, because my work is not important enough. I’m an illustrator and my work focuses on the long term effects of war – not on Russian politics specifically. Before On Tyranny, I worked on projects about WWII and German history. At the time, I received occasional negative comments from the far right.

Is it perhaps easier to perceive such painful stories through the filter of drawing? In addition, the drawings even help keep the main characters anonymous. What other strengths are there in this medium?

Like you say, drawing creates a distance, but at the same time it allows you to get closer to the material, to the subject, to the truth. It sounds like a contradiction, but it’s not. Drawing helps drawing you in, in a way that mere text can’t. Illustration in itself is a political medium. Illustration has been abused for propagandistic purposes for centuries, but drawing has also helped us change the way we think in positive ways and change our societies for the better. I’m very aware of the history of my medium, and thus I think that expressing myself through drawing comes with a responsibility. Through my work, I try to break down stereotypical notions of culture, society, politics, history and war. My main goal is to dismantle some of the ideas that we have about these processes and experiences, and to reshape the way we think about them. I think illustration can do that in a powerful way because it’s a very emotional and poetic art form.

Yes, the big societal scale is taken down to the individual scale. In Diaries of War, the illustrations often show the perspective of the subject. You can see K.’s and D.’s hands with mobile phones or other everyday objects, for example. It can be very intimate. Reading the book, I pictured the world from inside their heads.

I didn’t want the images to attract too much attention because that would have competed with the intimacy of the protagonists’ tales and made me more important than them. I wanted the images to convey something internal by showing the protagonists’ hands and everyday gestures. This kind of perspective is often, and for understandable reasons, missing in the coverage of war. But in order to understand war, it’s very important to capture individual experiences.

It seems like nature and art can have a therapeutic effect. D. says ’My art is a kind of anchor for me.’ Is that something you have experienced yourself?

Nature and animals are the two things that really can calm me down. Unfortunately, there’s not all too much nature around me here in Brooklyn. Art making isn’t really a meditative process for me, and I don’t always find it enjoyable. I think a lot about the concept, composition and technique, and I often struggle when I work. That said, my making books is the only thing that keeps me from feeling melancholy about the state of the world. In that sense, it is a comfort. For me, illustration and writing is a way of thinking and reflecting about the world, filtering the world through my own viewpoint to make it visible to others.

You have mentioned that we have a collective responsibility. How can one deal with earlier generations’ difficulties, violence, crimes etc without feeling guilt and self hate? And why should we deal with it at all?

The simple answer to that is that as long as there is racism or hatred towards any group in a society, we have to continue to confront the past, and make sure the past won’t repeat. Germany is a good example of a country taking collective responsibility. Schools are teaching children about Germany’s role during WWII. But equally important is individual responsibility. I think it’s very easy to hide behind the collective guilt. In my opinion we need to take individual responsibility because that is where the real confrontation happens. But unfortunately, people aren’t willing to embark on this inner confrontation. Many are afraid that it might taint their family if they find out something bad about family members, or that their sense of national identity might be soiled. I think that’s a misconception. I think we can look at the dark moments of our country’s past and still love our country. For me, that’s what patriotism really is. It’s not loving a particular, positive moment in history, it’s to embrace it all, and to confront it all. If you have a sick child, or a child with psychological issues, you have to commit to this child and try to help it. Embracing your country includes both the bad and the good memories.

I’ve read that you inherit previous generations’ traumas – physically!

Yes, that’s something that’s been talked about a lot when it comes to families of Holocaust survivors. But it’s also true for Germans, not only in relation to WWII, but some people think that the sentiment of the German Angst actually dates back to the Thirty Years’ War in the 17th century. In some areas of Germany, 40% of the entire population was wiped out back then. Not only directly by the fighting, but also because of cholera and th pest, which were, in part, outcomes of the war. Germany is situated in the centre of Europe, and there were so many wars that took place on German soil throughout the centuries, and that does something to a culture, to the way we think and feel. A cultural phenomenon that I’ve observed is that Germans often immediately think of the worst-case scenario, and that Germans generally have a strong need for security can be dated back to all of our wars.

Speaking of generations and families, has having a child yourself changed the way you work?

Yes, it has helped me focus. My daughter is German and American, and it’s very important that she understands her German heritage, including that of WWII. In that way, my dedication to that subject has intensified. I want her to understand what happened and what we can do to avoid it from happening again. At the same time, I don’t want her to grow up with the same feeling of guilt and shame that I grew up with. I want her to be confident about being German. This makes me more committed in my work, because I see in her as someone embodying a continuing awareness of our past.

How do you do that?

By explaining the complexity of the matter. Most Germans supported Hitler, but not all Germans were bad. We still don’t learn a lot about the German resistance movement. Tens of thousands of Germans died because they resisted the regime. It may be a small number compared to the overall population, but it’s a larger number than I thought. I’m trying to replace the word guilt with responsibility. I also tell my daughter a lot of positive things about contemporary German culture. I want her to know that German society is very progressive. We go to Berlin every summer, so she experiences the culture, not only from afar. I speak only in German with her.

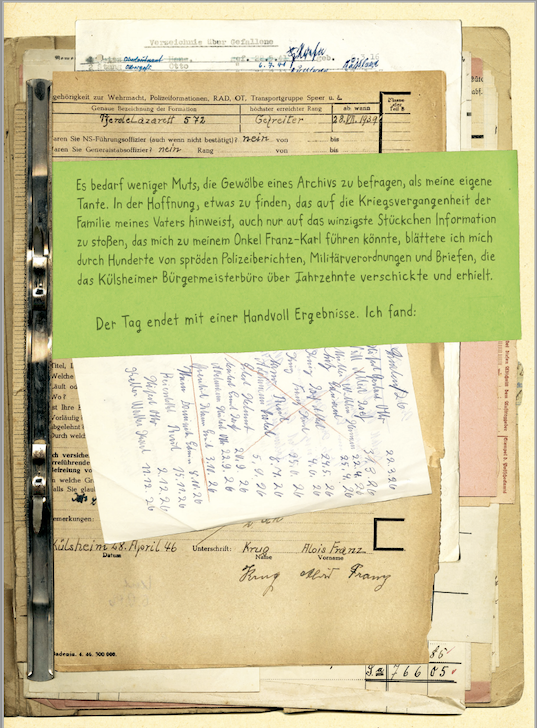

In the graphic novel Heimat (2018), you use the famous figure from the German Romantic painter Caspar David Friedrich’s paintings, seen from behind, looking at a landscape. Tell me more about that, and also other sources of inspiration!

There were several reasons for why I used this recurring motif. The Romantic period was a very important time for Germany’s self-identification, and it still shapes the way we see ourselves today. When I worked on Heimat, I went to several flea markets in Germany and searched for old postcards and photographs. I was interested in what people took pictures of over the course of 100 years in Germany. How did we see ourselves, and how was that perspective represented in these photographs? I found so many pictures of Germans looking at landscapes from behind. I asked myself if Friedrich’s painting is so strongly embedded in our collective cultural consciousness that we keep repeating it automatically in our own photographs? Walking and hiking in nature is an important aspect of German culture, but so is the idea of the lone individual, looking at a landscape. I also used this figure as a symbol for me looking at my family’s and Germany’s past, but from a distance – the geographical distance with me being in America, and also the generational distance. I grew up in the second generation after WWII, and it’s this distance that allows me to get closer.

When I work on my books, I don’t look at that many visual works, I’m more influenced by non-fiction writing, and also by documentary films that have a personal, poetic and essayistic quality. Werner Herzog is one example, and also Joshua Oppenheimer, who made The Act of Killing. Film makers work with text and image as well, in a both poetic and reflective way.

What is your next project?

I was offered a one-year fellowship at Yale University beginning this fall, in the Fortunoff Video Archive for Holocaust Testimonies, the largest archive of video interviews with Holocaust survivors. I was invited to spend a year researching and creating a project that hopefully will lead to my next book.

That sounds very interesting – and also demanding.

Yes, well, it takes a long time for me to make a book. Heimat took six years. I’ve decided that this is the kind of work I want to spend the rest of my career doing. I don’t see each book as an individual stand-alone project, but as looking at the same subject from different angles. Each book is a part of a larger body of work. Heimat was a memoir, On Tyranny was a guide book, Diaries of War is my first project on an ongoing war, and it’s visual journalism, which I had never done before. For each project, I use a different technique or approach, but it’s always a reflection on war because I think that war is one of the biggest problems on our planet – and one of the few that we can actually avoid. The underlying questions in all of my books are: Why do we wage war, what can we learn from them, and can we ever forgive each other? How can we make sure there’s lasting peace? War makes me angry, and I think the anger is partly what is fuelling me in my work.

Nora Krug will attend a conversation about her work at Litteraturhuset in Trondheim the 4th of February.