A Strange and Fascinating World

Reviews, Peik Elias Greaker 08.04.2022

The entire second floor of Trondheim kunstmuseum is given over to the multiartist Hege Lønne (1961–2018). Who’s she, you might be thinking? Lønne grew up in Trondheim and studied at the city’s Academy of Fine Art. The reason why she hasn’t become a household name in her native Norway is that she spent most of her working life in Poland.

The dates in brackets after her name indicate that she is already deceased. And that she died not very long ago and relatively young. The exhibition is a retrospective that covers broad chapters of her nearly forty-year career. Impressive in size, it presents an incredible variety of expressive styles, idioms, media, techniques, and themes. The works range from stop-motion animations, videos, and photography to figurative and modernist sculptures, metal tapestries, and ready-mades. In total, it is a show of great diversity, which, despite an appearance of restraint, is full of vitality. A tangle of undergrowth that begs to be explored, but where one could easily get lost. A number of major themes run through the exhibition, even if sometimes difficult to grasp in their entirety. The works tell a range of stories in many languages, thereby raising more questions than they answer.

Works from different artistic genres and a broad time spectrum are displayed side by side. Some of Lønne’s late works, a series of smooth, amorphous, plaster sculptures, are arranged on horizontal plinths. Some are oval egg-like forms perched on plaster stilts, others are small, smoothly polished hillocks or rocks. The plaster has been applied in softly coloured layers, grey and pale blue, creating an impression of marbled stone. The minimalist idiom is reminiscent of modernists such as Aase Texmon Rygh, but whereas Rygh’s forms seem open, monumental, and abstract, Lønne’s are more down-to-earth and human.

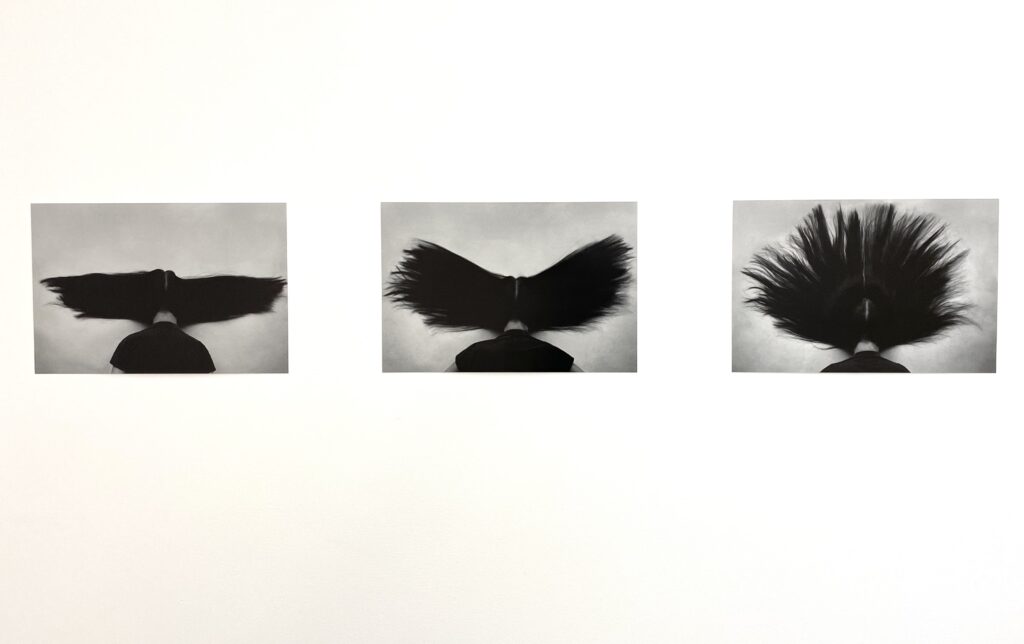

Alongside these sculptures hang a trio of black-and-white photographs with the label Uten tittel (Untitled) (1984). From early in the artist’s career, these pictures depict what we take to be the head of one and the same person. What distinguishes the three images is the different directions in which the hair is spread out. The symmetrical arrangement suggests the silhouette of an eagle, thereby alluding to one of the themes that run throughout the exhibition: nature / human. Perhaps the rounded plaster sculptures also fall into the category of the nature theme. They suggest stones polished by water or models of hills, while those that float above the “counter” could also be viewed as some kind of fancy electrical device. Like the kind of speakers you might find in an Apple Store.

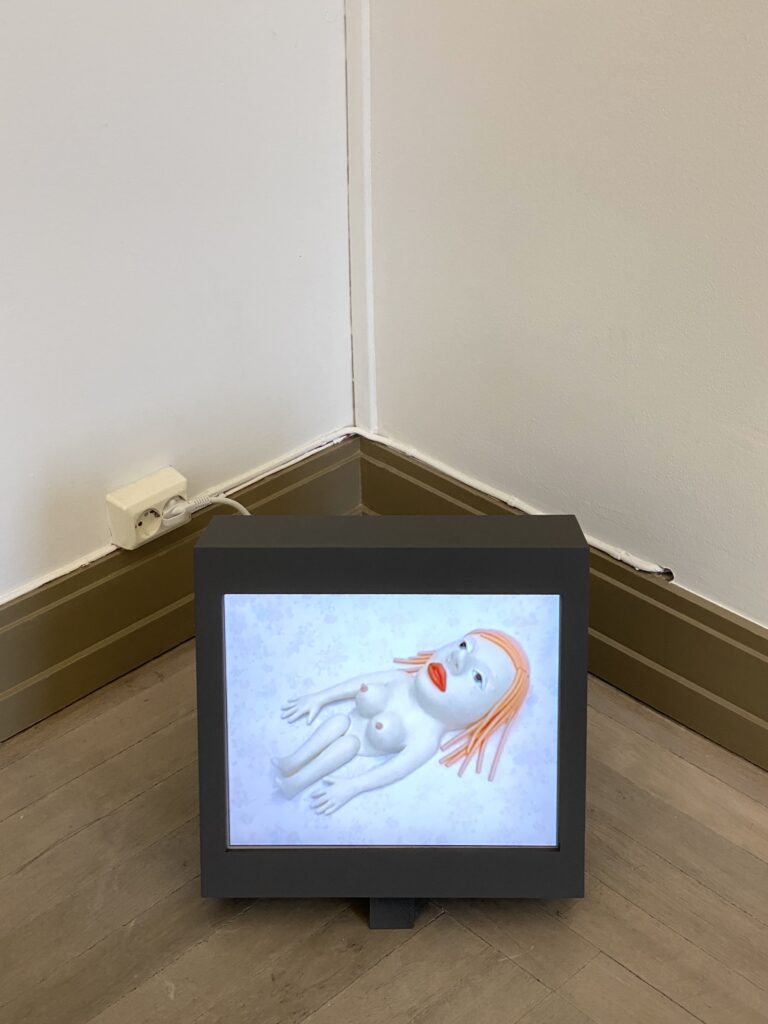

Whereas the sculptures and the black-and-white photographs are subtle in their expression, the stop-motion animations in the same room use a different approach. The Sweet Polish Feminist (2003) shows a pink anthropomorphic figure spinning around on the floor. It occurs to me that at present the rights of women in Poland are steadily being restricted. But what was it like back then, just twenty years ago?

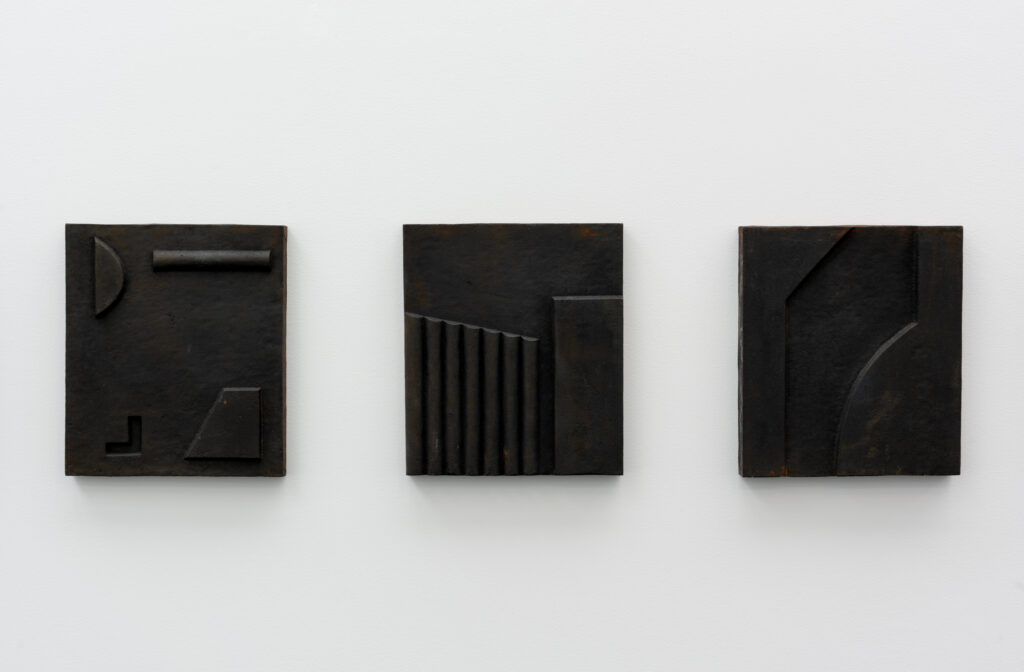

The mix of videos, photography, and sculptures works well in the more spacious rooms. Here one moves smoothly between the different modes of expression. In the smaller rooms, by contrast, some of the works compete with each other. The sound from a video work creates a mysterious atmosphere that isn’t particularly suited to the formalist idiom of the reliefs in cast iron. Here as well we find plaster sculptures with finely polished surfaces, although this time the style is rather different. The association here is with scale models of buildings or simplified landscapes. I am particularly struck by the sculpture Uten tittel (Untitled) (2008). This has a hole passing right through its body, meaning that where you stand as a viewer determines whether or not you can see light on the other side. The grey, smoothly polished surface has the appearance of bone, as if the ridge were a timeless fossil. The open plinth on which it stands helps to highlight the work. Even the surface of the earth beneath the museum is nothing but a crust.

The sculptures mentioned above fit in well with the nature / human theme, which I regard as one of the artist’s central preoccupations. But this is a broad category. For example, the main focus of interest in these works is, to my mind, nature’s grandeur, in contrast to the thematically more self-explanatory video of an ice block sitting on a Euro-pallet to the accompaniment of a ticking sound. And how does this theme fit in with the more lyrical nature video Puddle, which shows trees swaying in the wind, reflected in a pool of water?

In this exhibition, one could write a book about the videos alone. There are entertaining animations in a naive idiom, like the surreal Aeroflot – Russian Airlines. This shows a lengthy flight scene with a soundtrack of Mongolian throat singing. In Ranunculus acris, the Latin name for buttercup, we see a naked plasticine figure of a woman having a flower shoved at her face while a gruff male voice asks “Do you like butter?” It is both strange and funny, yet at the same time vaguely disturbing.

The video work Rogaland Arboret (Rogaland Arboretum) has an air of mystery. Initially it seems as if all we see are tree trunks, but for the patient viewer a group of people eventually emerge from behind them. Each person takes a few slow steps before hiding again behind another tree trunk. Trees and people merge into one, and the whole time I’m expecting something to happen. If this video had been put out on the internet, it would need to be accompanied by the instruction “Wait for it!”, otherwise no one would have had the patience to watch.

There are also sculptures that speak an utterly different language from that of the sober plaster objects. The mobile pieces Uten tittel (Untitled) (1989) feature models of old style fighter planes mounted on the end of rotating arms. In the year that saw the fall of the Berlin Wall and the opening of Eastern Europe, the world must have seemed chaotic. As it does again today. War is always topical, because that’s how the wheel of history turns. But although the work carries serious overtones, the model aircraft and the movement make it seem playful and humorous. Despite this pleasing ambivalence, to me personally, the understatement of the plaster sculptures speaks louder.

Lønne applies an exploratory approach to art production while consistently looking on the world with a gaze of wonder. Mixed together, the assorted works fill the rooms in a way that makes them more accessible, creating a landscape that allows us to experience art physically rather than just see it. At the same time, the presentation also gives the impression of something chaotic. Lønne’s modernist inclination to label her works with the term Untitled gives plenty of scope for interpretation, but it also leaves us feeling abandoned. I search the rooms in vain for an explanatory text or some supporting context. It is courageous of Trondheim kunstmuseum to devote so much time and space to a relatively unknown artist, and they deserve praise for the number of works they have managed to assemble. Even so, at times the collection seems somewhat bewildering.

I am left with a series of unanswered questions. What is it that connects these works? What is the theme here? What aspect of nature is the artist addressing? What did the use of Untitled really mean for Lønne? What was the struggle for women’s rights like in Poland in 2003? How did Lønne die? All in all, this mass of questions seem to chase and eventually consume each other. As already said, there are several parallel threads running through the exhibition, but they are so poorly defined as to seem vague. Hege Lønne, Retrospective at Trondheim kunstmuseum is a complex exhibition that raises more questions than it answers.

Hege Lønne (1961–2018), Retrospective

Trondheim kunstmuseum, Bispegata

March 25–14 August 2022

Hannah Ryggen Triennale 2022

Original text translated by Peter Cripps / The Wordwrights