Somewhere between activism and fanaticism

Opinion, Stedsfornemmelser, Text Series, Anki Gerhardsen 05.12.2019

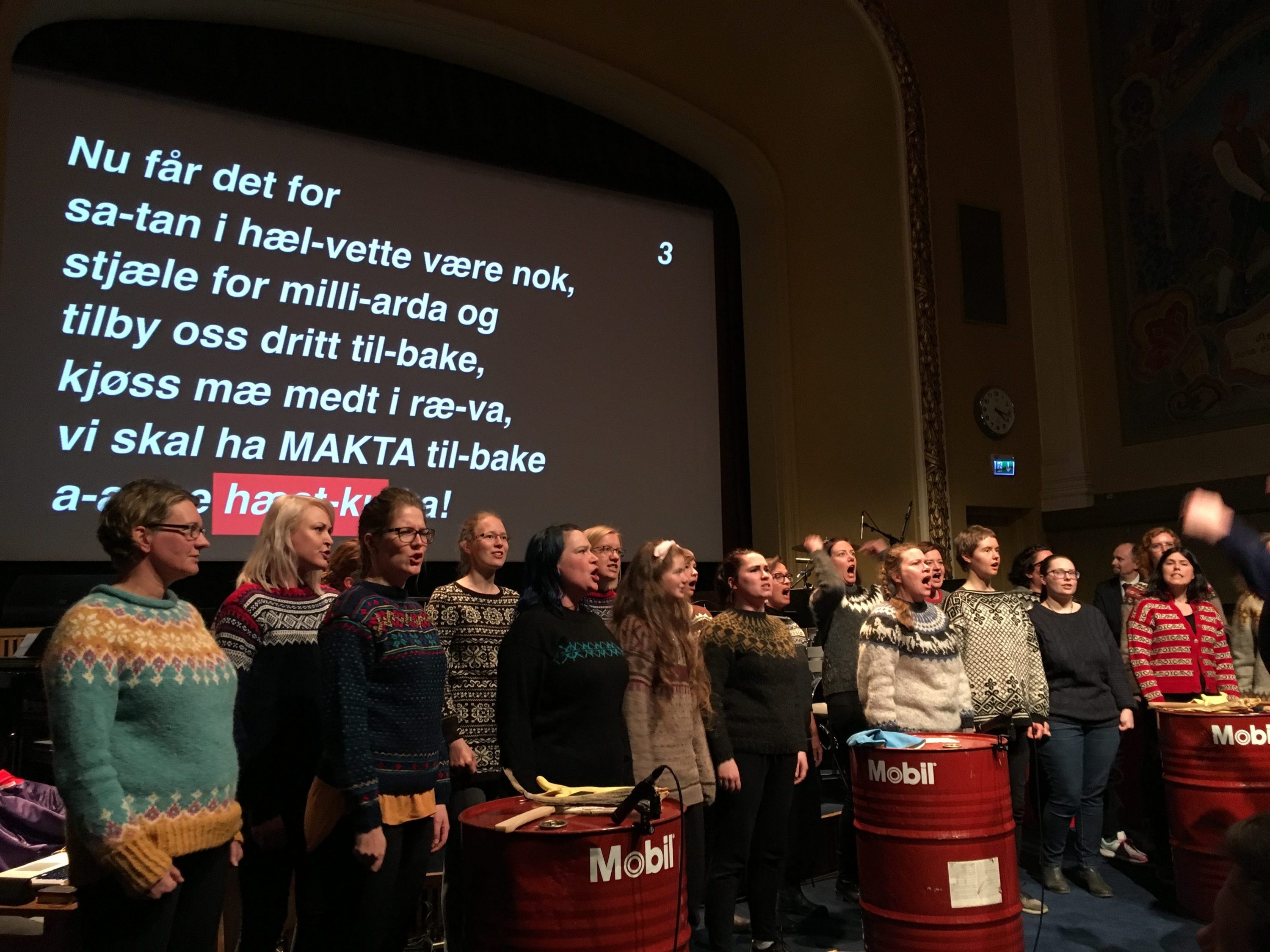

“We’ve bleedin’ well had it up to here we have

millions nicked and shit in return

go stuff it where it stinks

we want our FISH back

you lousy tossers”

It’s just gone eleven in the morning. It’s Sunday, 23rd June 2019, the Arctic Arts Festival is in full swing, and over at the headquarters of the Nordting party in Harstad they are holding a “Service for the North”. The congregation, or audience, are singing the Bangsund Song. It was named after the fisherman Vegard Bangsund from Vardø, who wrote the memorable lyrics in a fit of frustration and posted them on his private blog. And while the congregation sings, president, party leader and performance artist Amund Sjølie Sveen prepares the blessed sacrament: a shot of Russian vodka and a capsule of plankton. Outside, a light summer rain is soaking the enormous sun Sveen has painted on the town square. One of its rays reaches out like a fiery red carpet straight to the door of the party headquarters.

The day before, Sveen was responsible for the festival’s opening performance on that same square. Standing high up on a massive stage, he delivered an eloquent speech about the plundering of fishery resources in the north, the scourge of capitalism and the value of plankton. Knowledgeable, factual and to the point, served up with dance, flag-waving and music from a local brass band to a large crowd, who laughed, cheered and either raised or lowered Nordting’s red ballot papers when the time came to vote on the political questions.

I join in for the last verse of the Bangsund Song while thinking about the role and function of political art for people in Norway. Just a few years ago it was feeble and remote, almost nothing to speak of. It was overshadowed by reality fiction and stories of individual trauma and pain. But suddenly something changed. What was it? The climate crisis? The re-discovery of man’s insatiable hunger for self-enrichment? The rise of identity politics on the other side of the Atlantic? Whatever it was, art changed, and suddenly, there they were: theatre groups brooding on the future of the Arctic. Displays of Sami wrath outside parliament. Performances with free hand-outs of yoghurt culture, while the 2017 Lofoten International Art Festival broadcasted worried, critical reflection about the future to every corner of Henningsvær.

Artists working in many genres showed a notable interest in politics, although this didn’t always translate into exciting art. Many of the narratives were all too predictable, and the accounts of the world too one-sided. When I reviewed the festival in Henningsvær for the newspaper Nordlys, my article had the heading “We who know why the end is nigh”. I wrote that it was difficult to see the difference between the festival programme and the Green Party manifesto. I tried to address the question of whether socially-engaged art of the kind that seeks to operate in our midst loses its power to influence if it fails to portray the world as a more complex, nuanced and contradictory place than the politicians and ideologues make it out to be.

It is this ability to be complex, nuanced and contradictory that makes Nordting so fascinating.

Facts and vodka

Social critique and the critique of capitalism in particular have always characterised the art of Amund Sjølie Sveen, often through the medium of public lectures and musical works. In effect, Nordting, which first emerged during the 2014 Arctic Arts Festival in Northern Norway, is just an elaborated version of the same thing – a staged vision of democracy and a public assembly. It too originally started out as a temporary project to articulate criticism of Statoil and a cultural sector wallowing in oil money – as was the festival itself. But the project sparked so much debate and enthusiasm that it clearly had the potential to expand. Since then, Sveen and his team – dancer-choreographer Liv Hanne Haugen and composer Erik Stifjell – have notched up a total of forty-nine public assemblies, two of them abroad.

Sveen’s Nordting* events mix political appeal with lots of facts, statistics and humour. The oil industry and fisheries policy are always central themes. In addition to invited guests on stage, the assemblies feature singing, stockfish drumming, local bands or orchestras, fitness sessions (usually referred to as “people’s movement”), vodka (always vodka) and votes. Nordting has travelled the region visiting village halls, community centres and cultural institutions. It has asked people to vote on issues of varying relevance to the far north: should northern Norway become independent from the rest of the country? Can the fish-farming industry be trusted? Should local people kick out the tourism companies and take back control of the North Cape plateau? Should safaris be organised to look at the houses of the richest people in the city?

Nordting has organised ballots in buses and barns. They have marched under their own banners and to their own music in the annual May Day procession. And they have set themselves up as a political party, winning 59 votes in the parliamentary elections of 2017. Amund Sjølie Sveen and his crew incisively capture both north Norwegian frustrations and the myth of the archetypical northerner. They uphold the view that the periphery suffers from centralised power. They deliver speeches about living conditions in coastal fishing communities. They sing Unit Five’s old hit “Æ e Nordlænding æ” (I’m a northerner I am), and talk about the depletion of resources. They give people a much needed opportunity to collectively shake their heads at the “quota barons” and the insatiable greed of Equinor. Nordting gives voice to the exasperation people feel in response to regional reforms and stood for election on an explicitly separatist platform. And all of it with massive support from the local population, i.e. its audience.

Contemplative activism

Many artists have tried to break down the fourth wall, but Sveen has succeeded with a vengeance. “He wants to separate off northern Norway,” writes one reporter in Aftenposten, while the newspaper Itromsø argues that Nordting’s logo should be adopted as the official coat of arms for the county of Troms og Finnmark. Harstad Tidende made it front-page news when the regional health officer filed a formal complaint against Nordting for the illegal serving of hard alcohol, and the aforementioned Bangsund announced his candidacy for mayor under Nordting’s slogan “Make the North Great Again”.

All of which creates an unpredictable and dynamic mix of determination and chance, structure and spontaneity, risk and control. Nordting blurs the divide between art and reality, clearing a space for discussions anyone can get involved in. At the same time, the project also asks questions of itself.

Because, although there’s no mistaking the political standpoint, and although Nordting’s activities can definitely be described as activism, the phenomenon is also a reflection of society. Sveen positions himself somewhere between Berthold Brecht and the fool. Brecht because he seeks to use art to change society. The fool because he wants to force us to look at ourselves. Sveen’s art project is a subtle blend of genuine political conviction and a critique of genuine political conviction. Sveen wants a political revival, but at the same time he insists that nothing is as simple and sincere as it seems. It’s one thing to vote for a replacement to the current mayor, quite another to clap and sway while chanting “Praise the North!” and abandoning oneself to what can only be described as a kind of political-religious mass hypnosis.

In other words, Sveen plays quite openly with the techniques and effects we usually associate with charismatic authoritarian figures: the allusions to communion, the red-painted reference to communism out in the square, with one sunbeam leading to the gathering of the enlightened, the party office, people chanting in unison, moving to the same beat, and voting with red cards that they wave in the air. It fosters an “us” and a “them”. On the one hand you have the rich, cynical elite, on the other there’s us, our community with its values, out here on the public square.

To me Sveen seems eager to demonstrate the reality of this distinction, using his art as a means to achieve a transfer of political power. But at the same time, everyone who takes part in a Nordting event is made to feel uncomfortable about the consequences of dividing the world in this binary way. Also to see themselves through the eyes of the fool: Who are you when you’re here? And it is this that elevates Sveen’s project above mere creative activism and makes it profoundly thought-provoking and immensely important. Absolute certainty, anger, and the demand for immediate action are the distinctive hallmarks of populism, and populism is taking hold wherever we look. It was evident in the election of an anti-politician to the position of US president and world leader. We hear it when the right-wing Alternative for Germany chants “We are the people!” Isn’t it also populism when a comedian gets elected mayor of Reykjavik? And what knock-on effects Brexit will have for Europe as a whole we have yet to see.

This is the tangle of issues into which Nordting drives a wedge: Maybe it’s true. Maybe the thing you’re fighting for is right. Maybe it’s time for action. But it might also be dangerous.

*The name “Nordting” can be translated as both “Northern assembly” and “Northern thing”

Article photo: Nordting

Translation by Peter Cripps.

The English text is financed by Trondheim municipality.