A Smorgasbord of Conflicts

Reviews, Peik Elias Greaker 07.03.2022

At first glance, the exhibition Exotic Dreams and Poetic Misunderstandings – Still Life by Lin Wang has the appearance of a mouth-watering banquet, but the more I have of it, the worse the aftertaste it leaves in the mouth.

Trøndelag Centre for Contemporary Art is filled to overflowing with porcelain fruit, fish and birds. Realistic oysters exude an odour of class and aphrodisiac. Here I find raspberries and figs so delicate they make me want to bite the white porcelain. The abundance suggests a level of greed that can even prove fatal. For lying on one plate we find a human head garnished with fruit and shells. The colourless porcelain skin is both lifelike and morbid at one and the same time. A little further on, I glimpse a scrap of pale pink flesh with the tattoo of a pin-up girl. The exhibition is so full of contradictory impressions that it forces me to abandon the stance of the detached viewer. I come to a standstill in the midst of all this gluttony. What should I make of this smorgasbord of conflicts?

The allusions to classic still lifes is obvious. Naturalistic paintings of luxury goods, flowers, bones, and animal carcasses – historically, these were objects charged with symbolism. Wang also mixes in non-ceramic items. Two real pink crab claws protrude from a gilded knucklebone. A string of sausages hangs from a blue-glazed Chinese vase. They smell of rancid fat. This mix of meticulous replicas and genuine organic elements blurs the line between art and reality. The works become embodied and relevant. The porcelain figurines refer not just to historical still lifes. Other clear associations include modern kitsch, such as Jeff Koons’ Michael Jackson and Bubbles. Inevitably, one finds oneself asking: Is it beautiful or grotesque?

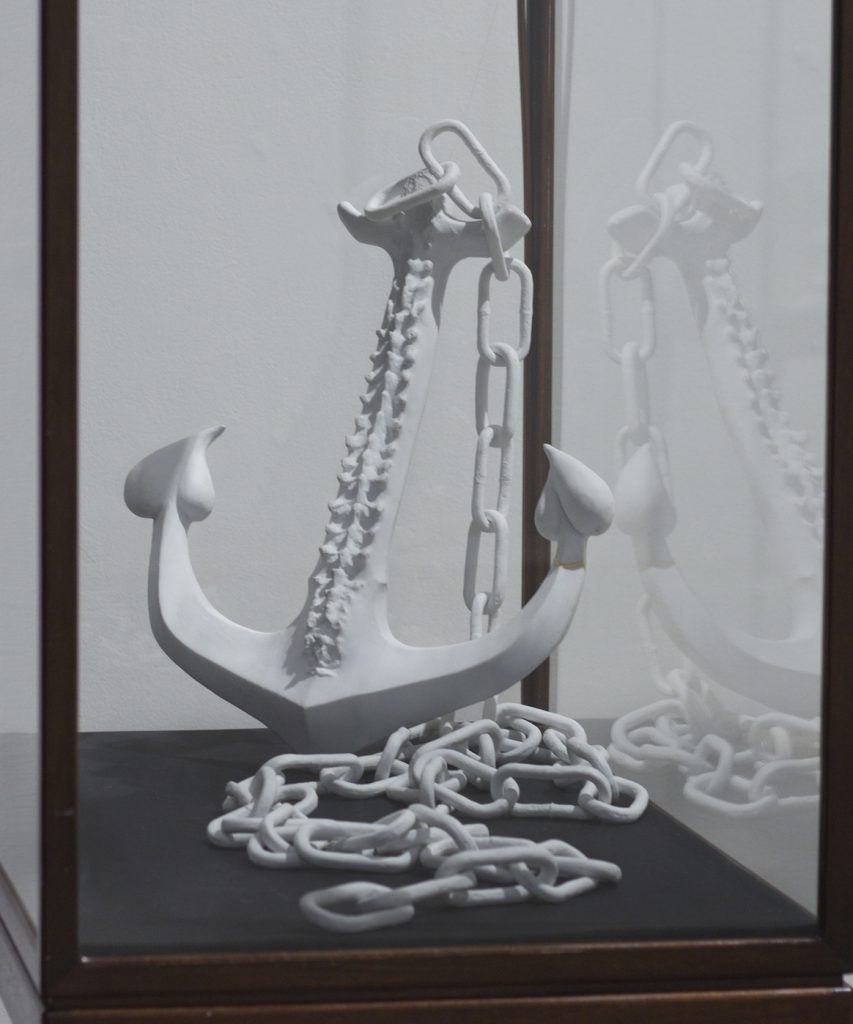

The first work, Souvenir I, is a white anchor. But this is no ordinary anchor, because the shank is a backbone and the flukes on the two arms are hearts. One of the flukes has broken off and been glued back on leaving a line of gold around the fracture. It is probably a reference to the Japanese technique of kintsugi, meaning roughly “golden repair”, a close relative of the wabi-sabi philosophy. In a nut shell, the latter describes the love for all things used and imperfect, for the story that lies in an object.

With its wealth of references, Souvenir I is representative for the entire exhibition; the longer you look, the more the works open up and share new stories. The anchor hints at sailing ships and the historical trade with the East. “Exotic” goods such as garlic, porcelain, and peacocks were shipped between the continents. It was a trade based on violence and imperialism, on human bones and broken backs. This brutality is evident in the other works on display. Attractively arranged among sweet fruits are scraps of flesh, dead animals, and crockery shards.

The critical perspective on European exploitation during the era of the Silk Road runs throughout the exhibition, yet there is also a different, more admiring view of the superstitions of seafaring culture. The anchor is a symbol of hope. Its structure includes a cross, which stands for faith. The heart signifies love. Wang puts tattoos of mythical beings on both porcelain and bodies. The exhibition includes three videos of people with tattoos. Although the videos are restrained compared to the sculptures, the use of tattoos is intriguing. And not just because of the direct application of cobalt blue to both bodies and porcelain; there are also less conspicuous associations. Tattoos are a global, timeless tradition. The 5,000-year-old ice man Ötzi, whose body was found in the Alps, had tattoos. In more recent centuries, tattoos became souvenirs for sailors, or signs of life as an outlaw, while today they are available to everyone. Today we uncritically adorn ourselves with a patchwork of styles and symbols from cultures around the world. An outcome of globalisation perhaps? We take a bit from here and a bit from there until we are all equal. And isn’t it the same fate that porcelain has suffered?

The largest sculpture in the exhibition, Souvenir – Globe Girl, shows a woman holding the globe on her shoulder. Almost life-size, she is rendered in a style that places her somewhere between a galleon figurehead and a pin-up girl. Her flowing, gleaming golden hair stands in marked contrast to the plinth: a worn out, grey-brown Euro-pallet. A contrast that captures the conflicts inherent in the exhibition: luxury and exploitation, original identity and new ownership, past and present. The Euro-pallet tells us that the Silk Road is not a thing of the past. Goods are being sent from east to west more than ever before. But what used to count as luxury merchandise has now become mundane and the stuff being shipped today is mass-produced.

The work Still Life is an enormous buffet of ceramics, porcelain figurines, and real food. I latch onto a stuffed moth and a gilded butterfly, symbols of transformation. Whereas the latter is beautiful, a metaphor for freedom, the former has a death mask on its wings. As everywhere in this opulent exhibition, here we are confronted with references on many levels and the range of possible interpretations is broad. Latent within these beautifully rendered figures, the stories wait to be unravelled. This is an exhibition where you could spend hours reflecting and interpreting without getting bored.

Lin Wang

Exotic Dreams and Poetic Misunderstandings – Still Life

24 February–27 March 2022

Trøndelag Centre for Contemporary Art

Original text translated by Peter Cripps / The Wordwrights