Art as a Climate Cop-out

Opinion, Polare randsoner, Text Series, Eline Bjerkan 04.02.2022

The MS Polargirl has reached the highlight of her journey, the Nordenskiöld glacier in Billefjord on Svalbard. Pale blue gashes can be seen in the areas where the ice has recently calved. There are birds attracted to the small fry, which in turn are searching for plankton. They take to the air as the boat nudges past chunks of drifting ice. The glacier is important for this finely tuned ecosystem, where for millennia polar bears have roamed along the crest. I have chosen to take this trip, in the full knowledge that tourism is helping to cause glaciers like this to melt and disappear.

Sightseeing tours similar to the one I am on are offered on a daily basis. There are stories of passengers clinking glasses cooled with ice from the glaciers. It must be the acme of experience tourism. If it were an art performance, it would count as biting social satire. Perhaps it is their faith in the moral rectitude of art that lets artists feel their consciences are clear, unlike other tourists who visit Svalbard for inspiration.

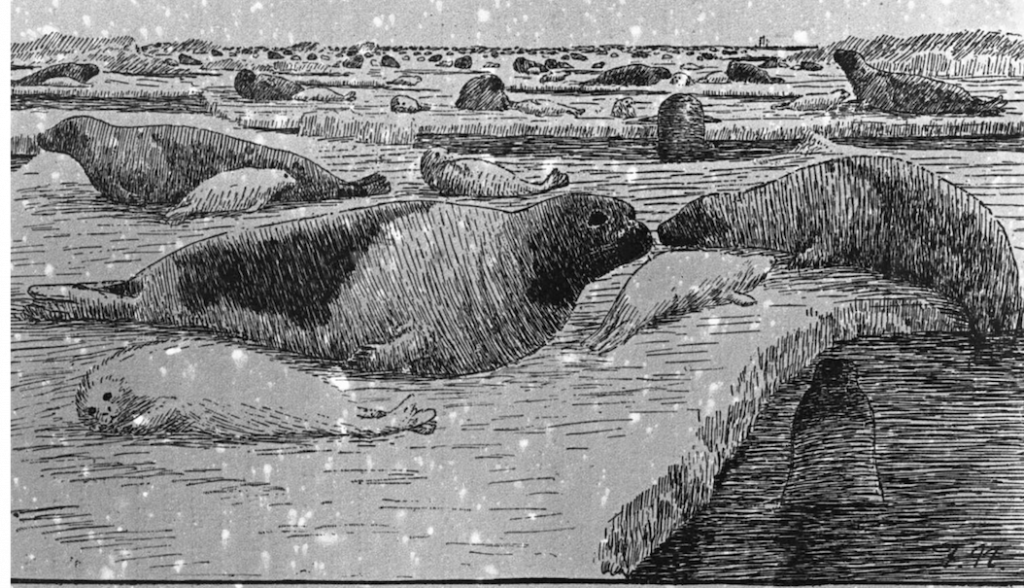

Svalbard is a popular destination for artists, both from mainland Norway and other parts of the world. Many of these visits have taken place in the framework of the PolArt project, a collaboration between Tromsø Kunstforening, the Arctos research network, and Troms Fylkeskultursenter (Troms County Cultural Centre). The fascination with the far north is in itself nothing new: Stig Falk-Petersen from the Norwegian Polar Institute, the driving force behind PolArt, points out that artists have traditionally played a part in documenting northern Norwegian landscapes and communicated scientific discoveries through the medium of the sketchbook.

“Many artists are also interested in science in what they do. Research and art have a lot in common. In many respects, researchers and artists speak the same language,” says Falk-Petersen in an interview with Forskning.no.

The collaboration was no doubt a veritable eye-opener also for the participating researchers. In the words of Paul Wassmann, a professor of arctic and marine biology quoted on the University of Tromsø’s website:

“We began to reflect on how perception influences the ways we think. Artists visualised aspects of our research that we hadn’t previously considered. Something happened to us on the ship.”

The prospect of such reciprocal insights sounds positively promising for both research and art. Is it too audacious to hope that such a marriage of disciplines could make a difference given the current climate and nature crises? Perhaps it will engender an environmental activism that is both fact-based and sufficiently rooted in emotion to galvanise the average consumer into taking action.

Several powerful forces seem to be working on the basis of such a hope, not least TBA21 Academy, an organisation funded by the baroness, philanthropist, and art collector Francesca Thyssen-Bornemisza. Describing itself as a “cultural ecosystem”, the academy aims to strengthen people’s relationship to the oceans and their sense of responsibility towards them through the medium of artistic activity. One outcome of this engagement was the 2018 exhibition Oceans: Imagining a Tidalectic Worldview in Croatia, curated by Stefanie Hessler, the current director of Kunsthall Trondheim. With renowned artists such as Sissel Tolaas and Jana Winderen, they were able to raise awareness for pressing climate issues. Tolaas collected ocean smells that are rapidly vanishing as ecosystems change, while Winderen presented sound recordings of marine animals ranging from crustaceans to fish and whales.

Tolaas and Winderen bring nature closer to urbanised life. On Svalbard, on the other hand, animals and landscapes are still an immediate presence; after snapping a couple of dozen pictures of the Nordenskiöld glacier, I head back to Longyearbyen and the polar bear-safe zone, where at last I can move around unarmed. There I meet Charlotte Hetherington, the director of Artica Svalbard, another organisation that flies in artists to the Svalbard residence programme. It seeks to facilitate artistic activity on the archipelago and to raise awareness for the relevance of the polar regions in relation to themes such as geopolitics, migration, and – unsurprisingly – climate change. Even so, there is plenty of scope here for misgivings:

“It seems self-contradictory,” Hetherington admits. “We try to reduce our carbon footprint by imposing the condition that an artist residence should last at least 6 weeks and that the artists should give something back to the local community.”

Here as well, every effort is made to facilitate collaborations between artists and researchers. Hetherington says that the first thing many of the visiting artists have to do on arriving in Longyearbyen is revise their preconceptions of the place. The expectation of a captivating pristine Arctic environment has to make way for the reality of a barren industrial landscape. The mining town consists of barrack buildings and massive pipes laid directly on the ground, since – for the time being – the permafrost still makes the soil impenetrable.

Norway’s commercial activities on Svalbard are, however, currently undergoing a transformation from a focus on fossil fuels to so-called sustainable tourism. It is a development that forms a central theme for Ignas Krunglevičius, Artica Svalbard’s artist in residence at the time of my own visit. Krunglevičius has moved into a decommissioned coal-fired power station, setting up the installation Hard Body Dyspraxia. This former industrial space has been transformed into a celebration of light and sound, with microphones, speakers and floodlights hidden around the rusting interior, which has been out of use since 1984. The audio dimension mixes processed aspects of the building’s own sounds with recordings from Longyearbyen’s industrial history. The work is a telling commentary on processes of change – both physical and idealistic – currently affecting the place.

Another person who seems to have undergone a similar wholesale reassessment of values is the fishing billionaire Kjell Inge Røkke. Having formerly engaged exclusively in destructive trawling, he now also funds marine research, here again with art thrown into the mix. Røkke is the owner of REV Ocean, a ship that serves not just as a research and exploration vessel, but also as a floating exhibition venue boasting 180 works of art by renowned artists. Specially commissioned and made for this context, the works address issues such as climate change, pollution, and overfishing. The curator of the project, Åse Kamilla Spjelkavik Aslaksen, is convinced that art can have an impact:

“As a means of communication, art has the potential to touch people and to stimulate curiosity, which can lead in turn to greater understanding and possibly even action. We need to foster empathy and a willingness to change if we are to improve our current situation,” she writes in an email.

The art field is zone of many contrasts. On the one hand, the life of the artist tends to be precarious and frugal, while on the other money gets poured into glamorous, transnational art events. Can an art exhibition on a research boat at the mouth of a fjord offset the destructive impacts of human life in any meaningful way?

Highly regarded by many ecologically oriented artists, the radical theorist Timothy Morton seems to be in little doubt. As an example of the influence of art, he mentions the best-selling album Songs of the Humpback Whale from 1970. For most people, it was the first time they had ever heard the rich song of the humpback whale. The album is described as contributing directly to the creation of the global environmental movement “Save the whales”, which brought about a ban on commercial whaling in 1986. According to Morton, this illustrates that art is far from being just a passive accessory: “Such reactions actually say something deep about art, in an upside-down way: art is causal. That’s what’s frightening about it.”

Despite this, and no matter how great its commitment to the climate and diversity, art and its production almost always leave a carbon footprint. People need to be more aware of what the use of art materials entails. We could view it as encouraging that the Dutch Jan van Eyck Academy has shown a commitment to more sustainable art production by launching “The Future Materials Bank”, a database detailing degradable and organic materials. A decision to use, for example, fish skin, sawdust, seaweed, and raw silk signals a circular production process rather than a use-and-throw mentality. This is of course nothing new for certain indigenous cultures, from which it would seem the rest of the art world has something to learn.

Perhaps in the future, vulnerable natural environments will be protected with the help of visionary and motivating zero-emissions art. In the meantime, one can easily succumb to our contemporary ambivalence, as did Randi Nygård, one of the artists who took part in a research cruise organised by PolArt:

“You believe one thing, but do something completely different, such as travelling to Svalbard, or flying around the world, despite your concerns about climate change (…) It’s paradoxical that the number of tourists and researchers visiting the place has increased due to the focus on climate change. I’m not sure I’ll be going back there,” she says in an interview with ArtScene Trondheim.

After her stay in Svalbard, Nygård presented the exhibition Isbreen pustar mens vi leitar etter den arktiske tåka (The Glacier Breathes While We Search for Arctic Fog) at Trøndelag Centre for Contemporary Art. This included interviews with researchers from Ny-Ålesund and charcoal drawings of glaciers.

Coal (power) and glaciers are highly charged with political significance – on Svalbard as elsewhere. Both are undergoing change, although no one can yet say whether supposedly sustainable technologies will be able to halt the melting of glaciers or to trigger a reaction. Like Nygård, I leave Longyearbyen with a degree of scepticism. I am also inclined to doubt whether the current text will offset my carbon footprint.

Article picture: Nordenskiöld Glacier, Svalbard. Photo: Eline Bjerkan.

Original text translated by Peter Cripps / The Wordwrights