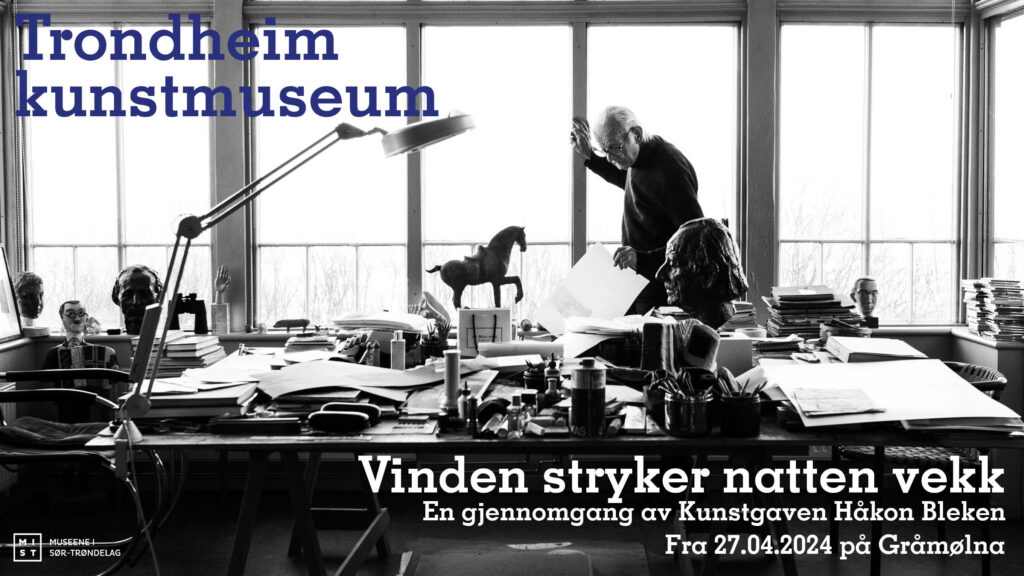

Siri Hustvedt: Intersubjectivity, Curiosity and an Ivory Hedgehog

Intervju, Märit Aronsson-Towler 26.06.2019

American writer Siri Hustvedt is ever relevant, be it with academic articles on anything from neuroscience to literary history, or with lectures, poetry, essays, and not least, novels. She has recently published the novel Memories of the Future, which also includes her own drawings. Visual art plays an important role in a number of her fictional stories and is the topic of many of her essays. When Siri visited Trondheim for a conference about the 17th century writer and thinker Margaret Cavendish, ArtScene Trondheim had the pleasure of meeting her and talk about what art can be.

Märit Aronsson: I’d like to start with a great question; what is art?

Siri Hustvedt: There is no consensus about what art is, but it is certainly not limited to the paintings and sculptures in a museum or gallery. Long before there was “art”, there were rituals and symbolic objects. I think of art as the creative impulse in human beings to make something outside themselves that in one way or another represents their experience of the world. It’s a social act that takes place between self and other and turns that between into an objective reality. Sometimes it is a concrete thing, sometimes not, but the urge to make is human, whether it’s a totem, a poem, or a work of conceptual art.

M: Could you please say something more about this creative impulse?

S: A couple of years ago I was in Tübingen giving a series of lectures at the university there. I was taken to the archeological museum, and in that museum there was a room with tiny ivory figures of animals that had been carved 40,000 years ago. They were all recognizable—bears, bison, horses. My favorite was a hedgehog, unmistakably a hedgehog. And yet, their forms were abstracted and beautiful. No one knows really what role those figures played in the life of that people, except that the animals must have been highly significant in their culture. But the impulse to make and represent is the same. This is my point. In Art as Experience, the American pragmatist philosopher John Dewey argues that although art has been turned into a rarefied, high-flown business, it comes from bodily processes we all share—our movements and our senses. He calls the thing that’s made “the expressive object.” That making is a human impulse.

M: So you don’t subscribe to the idea of the artist as a genius…

S: Haha, no, I’m very anti-genius. Another great person who deals with the area you could call the creative between or intermediate area is D.W. Winnicott, the English psychoanalyst and pediatrician, who identified the space where human beings find themselves in the eyes of another person—usually the mother. He invented the term “transitional object”—the blanket or toy a child needs for a while and then outgrows. The object isn’t inside the self, but it isn’t entirely outside the self either. Its meanings lie between the two. He locates art in this space, art and all kinds of creative activity, whether it’s the making of a pie or a symphony. These cultural objects, these objectiver Geist, are part of the intermediate area between self and other.

M: Could one say that this is something that everyone is doing, in one way or another?

S: Yes, I think everybody does it. An interesting further question is, are other animals doing it? It used to be thought that animals couldn’t use tools. They do use tools. It used to be thought that animals had no emotion. They have emotion or at least a range of affective feelings very much like human beings. Now, some scientists are wondering about culture and aesthetics in the lives of other animals. We can say, however, that in human beings the urge to make objects is more developed than in any other species.

M: Let’s talk about the experience of art. You have said that an artwork can only unfold for the viewer with time, and that if you comprehend an artwork very quickly, it’s not really worth looking at – you have called them ‘one liners’. What do you think makes an artwork worth looking at?

S: …In my own experience, what interests me is what I don’t understand. I am captured by something in the work of art that I need to keep looking at to understand, often something I am never able to fully grasp or contain. I like the uncontainable. I’ve written about Louise Bourgeois, whose work I first saw in 1980, and which continues to fascinate me. I keep looking at her works and keep thinking about what’s going on in them and how they affect me and their multiple meanings. Sometimes I laugh. Sometimes I see the same work again, and it’s not so funny. Maybe it’s a little cruel or tender, and I try to articulate what’s happening between the work of art and me.

M: Do you think you see what you need to see, in that moment?

S: I think human beings are dynamic, changing creatures, so no one can exactly repeat the experience of looking at a work of art. It hasn’t changed, but the observer has, and both of them are in another moment in time. Our perceptions change and the context for them changes. With complex, rich works of art, there is always something new to discover. I’ve had this feeling about many objects, from the hedgehog to Bourgeois.

M: You once wrote that each encounter with an art piece is subjective and takes place in the body. In what way is a perceptual experience physical?

S: We might not think we are influenced by ideas in Western philosophy, but believe me we are. We value intellect over emotion, the mind over the body, and that goes way back to Plato. The irony is that we don’t remember works that have no emotional punch. Feeling keeps memories alive. The strongest works of art, the ones we remember are those that make us feel something.

M: And through the feeling, it’s physical?

S: Yes, I belong to the embodied school of thinking. I am not a Cartesian. I do not think the mind floats over the body like a ghost. I do not believe in dualism—that we are two substances, psyche and soma. Emotions are bodily experiences.

M: So it’s very individual, or subjective, what kind of art you are attracted to?

S: My argument is that it’s intersubjective, not subjective. I do not think that any interpretation of an artwork is as good as any other. That would be a radically subjective position. The intersubjective is what’s happening right here between you and me. You and I are having a conversation. You’re real to me and I’m real to you, and the meanings between us are made in intersubjective space, not just by one of us alone. Most art doesn’t talk back, but in our culture we treat artworks as if they are carrying the traces of another human consciousness. I treat a painting or a sculpture differently from the way I treat my glasses case. It could be a perfectly nice case, but I don’t treat it with the reverence that I bring to somebody’s art. I was in the Kunsthall Trondheim the other day, where there is a beautifully curated exhibit.

The only artist I knew from before was Francesca Woodman, whom I admire. I walked through the show with high attention, feeling alert to what I saw, felt, and thought. I was looking at objectiver Geist. Another person’s meanings, experience, and seriousness seem to emanate from those objects and photographs, but I couldn’t create that alone. The relation I have to them is intersubjective.

M: Do you think that this replaces sacred, religious objects, as we are living in such a non-religious culture?

S: I think the culture has already have done this. You mentioned the genius ideas earlier, the cult of greatness which is often founded on the idea of a magical person, usually a man, who makes objects that are the sign of shining genius, and everyone worships him. This, I think, can be damaging. The name becomes a sign of greatness. People buy a Picasso, whether it’s a good one or not, just because it’s a Picasso.

M: I can think of it in a good way, too.

S: Oh, there is a good way! We do have a cult of greatness, and that idea of greatness is impregnated into the object, so people don’t really see the thing itself. They see it only as a sign of greatness. The other experience, the one you’re talking about, is the experience of an almost magical or transcendent communication with the thing we are looking at, an encounter that is only for the thing itself.

M: When you speak of those pieces of art that you return to, and you discover layers in them or see them in different ways, depending on where you are in your life… In what state of mind, do you think, has the artist been able to create such a work?

S: Well, we can’t know that, right? But much of making art is unconscious. I have been drawing all my life. My latest novel has 12 of my drawings in it, so I know the feeling needed to draw, the feeling of looking at someone in order to draw her. If I were drawing you, I would feel as if I’m touching you. There’s a tactile sense. The paper is a substitute space where I move along the lines of your body. Writing is my art, and I know that much of what I write is unconsciously generated. So even the artist herself is not always in a position to say how that happens. Things come. I think that’s one of the most interesting things about making art is that things come, things appear. We know, of course, that we are creatures of experience. When you’ve been working deeply with a subject for many years, let’s say mathematics, suddenly that long experience accumulates the ingredients for creating a new mathematic formula. The process in art is the same. The result is different.

M: I think curiosity is a strong force.

S: I think it’s an enormous force. Why are some people hugely curious about things?

M: You’re very curious!

S: I am. And I think that drive to know, to find out and to explore, is a deep need. We used to have a dog. When we took Jack on a car trip, stopped, and opened the door, he jumped out and ran around wildly, sniffing and checking out everything. This impulse is present in all mammals, a desire to get out there and explore. It can be thwarted, it can be beaten down and beaten out of children, out of adults, who are just going on auto pilot, who feel that life has been narrowed to such a degree that they are just getting through the days, and then curiosity becomes an interruption, rather than a welcome attribute of living. Artists are generally people who get pleasure from free exploration.

M: Speaking from the artist’s point of view, it would be very boring to know exactly how an art piece will end up looking.

S: I think you have to have an idea about where you’re going, but that place is not necessarily where you end. It’s a place to go, and then along the way, it can change. But you can’t go sideways. I worked on a novel that I realized I was going sideways instead of forwards. It failed. In narrative, there is a drive that moves you from one place to another. You can’t stay in one place and just get thicker.

M: I’ve never thought about that you could move sideways in a process, I’ve thought about it maybe more like moving in spirals or circles.

S: I think space is fundamental to all our metaphors. I have thought of certain texts as funnels; you start out wide and keep circling and by the end you have the much smaller space, not some final solution but a focused area.

M: And you usually talk about essays as having a main path with branches of smaller paths leading from it, and back again.

S: Yes, that’s a tree image. Spatial metaphors work for many texts. Once, a Mexican novelist I met at a literary festival was going around and asking other writers to diagram their books. He asked me about my novel What I loved. He said could you draw it for me? I thought Oh my God, and then I took a pencil and did it. He said most people think they can’t do it, but then they sit down and do something quite precise. I thought that was fascinating. Sometimes you have a spatial idea about a book.

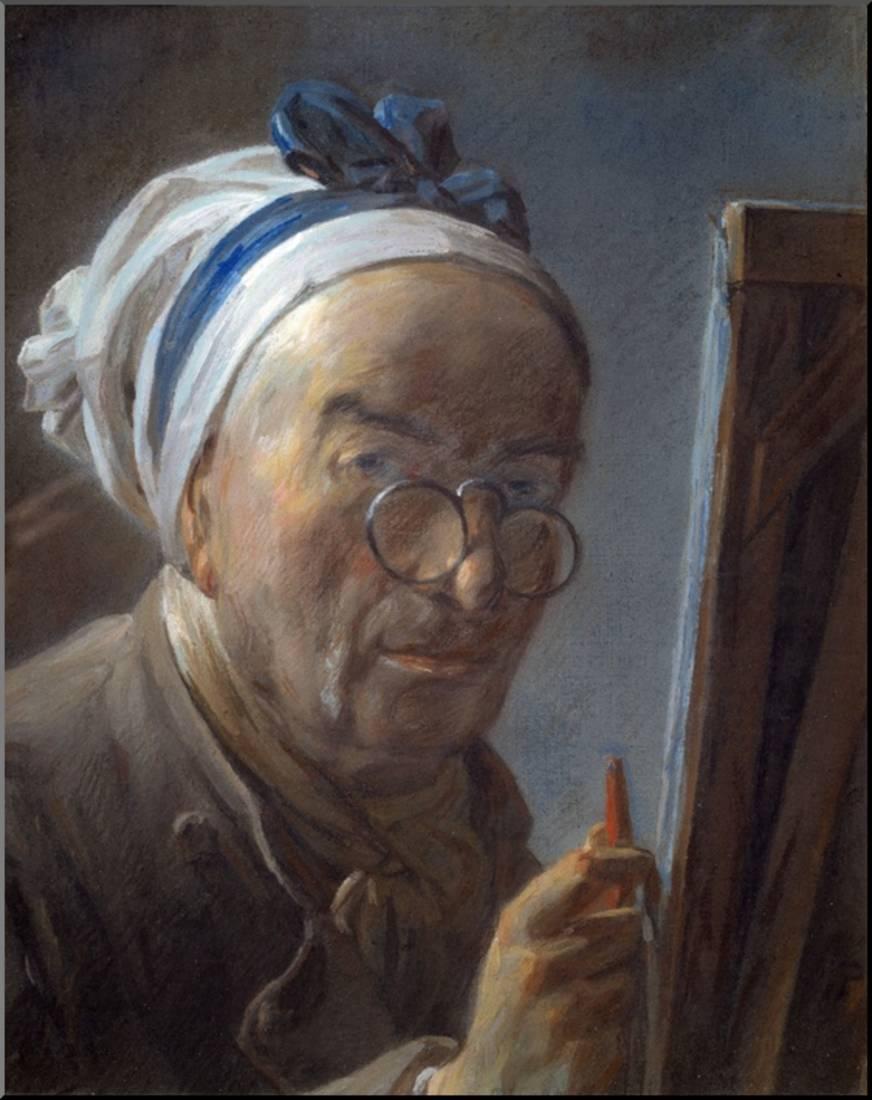

A beautiful one is Virginia Woolf’s drawing that explains To the Lighthouse. I don’t know if it was after or while she was working on it that she made the drawing. It’s two squares connected by a longer rectangle. I used this example in a text called Pace, Space and the Other in the Making of Fiction. What I wanted to talk about there is rhythm. Spaces have rhythms, too. We feel rhythms when we look at a painting. It’s not moving, but we nevertheless interpret or feel the movement of a brush or a stroke. It’s a part of our deep metaphorical reality. Even if something is static, we feel it in motion. I have asked myself why I wanted to cry when I looked at a glass of water and a clove of garlic in a Chardin painting? It doesn’t really make sense. In the real world, I don’t look at glasses of water and garlic and feel like crying, but there is something in Chardin’s touch that affects me strongly.

M: What is that?

S: I wrote an essay on Chardin called The Man with the Red Crayon. There’s a beautiful self-portrait of him looking a bit funny, with a kerchief on his head to keep his hair out of the way, and he’s holding a red pastel crayon. It’s wonderful! I think the artist’s hand is in painting. In Chardin’s still lives, you feel the human being who was just there with the fruit or the objects. He evokes the missing person. You feel the absence of the human presence and the tender caresses of Chardin’s brush. I do, anyway. But you have to spend time with the work and ask yourself what the heck is going on.

M: You once said that when you spend time with art, you want to be as open as possible. Do you have some kind of technique for that?

S: Concentration is essential, and plenty of time. I spend at least two hours with a work of art I want to get close to. I did a pod cast recently about the process. I was asked to go somewhere in New York and look at a picture. I picked Bellini’s St Francis in Ecstacy in the Frick Museum. I went there and spent about two hours looking at it. I always have a notebook with me, to make notes, and draw the shapes of what I see while I’m looking. The fact that it was a really famous picture dropped away pretty fast, after ten or fifteen minutes, and then I found myself in contact with this object and the story, the story in the picture and my story of looking over time at the image, and what I discovered in it. It can often take quite a bit of time to see the structure of a painting, or notice small, odd things about it. I don’t let my mind wander, but I try to be alert to associations. If something comes to you, there is usually a reason, and there is great pleasure in figuring out those links.

Artikkelfoto: Amalia Fonfara/Kunsthall Trondheim