Remote Walk

Intervju, Märit Aronsson-Towler 13.11.2014

KimSu Theiler is an American/Korean  artist who currently has a studio at Oslo City Hall. She primarily works with video and has shown her works at venues like the film festivals in Toronto, Rotterdam and New York and The Gwangju Biennial, amongst others. For the exhibition The Moving Studio at RAKE she will show a three wall installation based on her walk between Oslo and Trondheim.

artist who currently has a studio at Oslo City Hall. She primarily works with video and has shown her works at venues like the film festivals in Toronto, Rotterdam and New York and The Gwangju Biennial, amongst others. For the exhibition The Moving Studio at RAKE she will show a three wall installation based on her walk between Oslo and Trondheim.

Märit Aronsson: You made a walk this summer, following the old pilgrim route from Oslo to Trondheim. It took you a month. You said:

I used the invitation to participate in The Moving Studio as a way to clear “free time” and define it as “work” in order to give the studio walk some approximation of the seriousness I gave it. The walk is not a pilgrimage, nor is it a walk for being in nature. It’s a way for me to make time and space for thinking about my work, that I do in my studio.

Would you define it as to make frames for the creativity?

KimSu Theiler: In America you aren’t “doing” anything if it doesn’t make money. Everything else is a hobby. The romantic notion of a person contemplating, and I mean in both the definitional and historic sense, has embedded in it financial support coming from ‘somewhere’ so the individual doesn’t have to worry about the daily concerns of what in our contemporary society money gives us: shelter, food, and surplus time to do our “hobbies”. My family and my non-artist friends don’t really know what a studio artist does. It might look like from the outside that we have a lot of unstructured time to do things white-collar workers do on holidays: read, go to museums, listen to music, go to movies, make objects. They can’t fathom that it’s actually work and when you are doing all those studio activities, you are looking and doing in a way that is critical and feels like everything is at risk. It’s not relaxing. Walking is something everyone can do and does if they are in any way connected to their body. Norwegians, I think, take this for granted. In America, except for a few coastal cities like San Francisco and New York, you drive three blocks away to pick up anything. So it means something to walk in America. It goes against the grain. Now something that is common to both Norway and America is this dominating concern with one’s body, or also known as health. So, the rational for walking is usually about doing something good physically. I want to bring the walk back to the romantic notion of taking time to think ‘framed’, as you asked, by the human scale of our step and not that which is augmented by our mechanical genius, i.e. bicycles, cars, trains, planes, rockets.

MA: You said your purpose was to create a video about the ability for the visitor, the stranger to a strange land, to make some connection to this foreign place and its people. You wanted to make ‘a reverse ethnography’ of Norway, using the words from The First Crossing of Greenland by Fridtjof Nansen to accompany your images. Did you make this video in the end, and will you show it at RAKE?

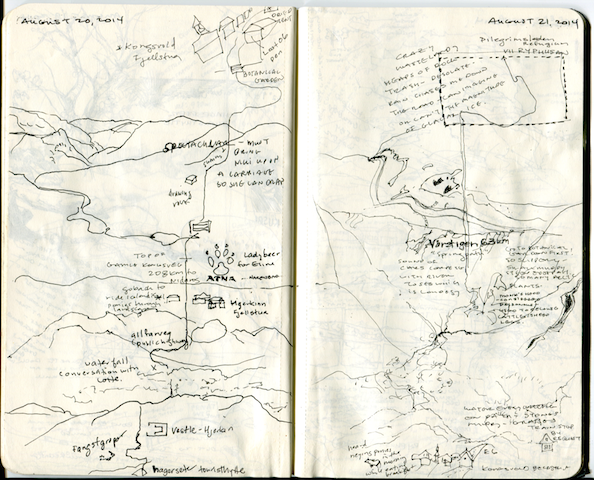

KT: No, I’m in the process of making it now.  My residency at Oslo City Hall is a year and a half long and I hope to shoot the video this winter. I decided to use half of the time for the pre-production phase which is exploring and defining the shooting script. It’s going to be crazy for the next three months because I have to translate the information and experiences into the concrete specifics of what I will shoot and shoot it. The studio-walk was an external investigation of some of the areas I am interested in exploring, but previously only have done through reading and image searches sitting down at my desk in the studio. The production phase will also have an exploratory element to it involving interviews and drawing. I haven’t drawn since art school, so one of the things I wanted to do on the studio-walk was basically reactivate my hand. What I stupidly didn’t realize going into the walk, but discovered along the way, is that as much as there is an adeptness that is eye-hand coordination, what really is going on for me is the interpretation from the brain to the eye, and back again. I lead with my brain, so I needed to understand what I was interested in seeing so that the eye and hand could coordinate without the brain being overly supervising and limiting. Once again, the romantic notion of having outlets for what used to be called unconscious thoughts I prefer to think of as perception beyond words. We experience more than we have words for. I think Norwegians can especially identify with that. I just read Kristin Lavransdatter and I was thoroughly confused through much of it because it seems like the characters don’t say anything to each other and in one sentence four people have been maimed and killed and birthed their third child, when before that sentence everyone was a virgin. Of course none of this is written out in the sentence, but the following five hundred pages tells you about the fall out from that one sentence. And then you realize a lot happened that no one said anything directly about.

My residency at Oslo City Hall is a year and a half long and I hope to shoot the video this winter. I decided to use half of the time for the pre-production phase which is exploring and defining the shooting script. It’s going to be crazy for the next three months because I have to translate the information and experiences into the concrete specifics of what I will shoot and shoot it. The studio-walk was an external investigation of some of the areas I am interested in exploring, but previously only have done through reading and image searches sitting down at my desk in the studio. The production phase will also have an exploratory element to it involving interviews and drawing. I haven’t drawn since art school, so one of the things I wanted to do on the studio-walk was basically reactivate my hand. What I stupidly didn’t realize going into the walk, but discovered along the way, is that as much as there is an adeptness that is eye-hand coordination, what really is going on for me is the interpretation from the brain to the eye, and back again. I lead with my brain, so I needed to understand what I was interested in seeing so that the eye and hand could coordinate without the brain being overly supervising and limiting. Once again, the romantic notion of having outlets for what used to be called unconscious thoughts I prefer to think of as perception beyond words. We experience more than we have words for. I think Norwegians can especially identify with that. I just read Kristin Lavransdatter and I was thoroughly confused through much of it because it seems like the characters don’t say anything to each other and in one sentence four people have been maimed and killed and birthed their third child, when before that sentence everyone was a virgin. Of course none of this is written out in the sentence, but the following five hundred pages tells you about the fall out from that one sentence. And then you realize a lot happened that no one said anything directly about.

MA: There is a walking movement in the world right now. There’s even a Museum of Walking in Arizona. I interpret it as partly a reaction to the increasing speed and efficiency in today’s society and a longing for a stronger connection to the ground, and the simplicity and the basic of just putting one foot in front of the other. Could you please tell me more about your studio-walks, when did you start and how often do you do them?

KT: First I want to respond to your observation about the impact of speed. During the St. Olav Pilgrimage walk, which roughly follows the E6 or actually the other way round, the E6 follows what has been the major throughway from Trondheim to Oslo for hundreds of years, I understood that the E6 is to get people between these two major destinations. Whereas walking on the old roads meant you really went to the town just next to you, and seldom further. Everyone basically stayed put. Why climb the mountain and go over to the next valley? A wedding, a christening, a death. There is a lot of time between those events in a life. Speed as in the ability to get quickly to the desired destination makes the character of the in-between insignificant. And the more insignificant it becomes the more efficient the route is. Walking changes all that. Everything matters, but nothing is exceptional in terms of one needn’t be extra fit, young, etc. I have walked as long as I can remember to think and clear my mind. I lived in the suburbs without a car until I was 16 years old, so I had to walk to the library and school. The monotony of suburban developments was stultifying so the walks didn’t become the walks I had read and heard about, such as the Camino de Santiago, the Appalachian Trail, William Wordsworth walking in the Lake District or Henry David Thoreau walking to and from Walden. Jump ahead a couple of decades and in 2011 I participated in the Walk Exchange’s second class. Two readings really had an enormous impact on me: Walking Meditation by Thich Nhat Hanh and Reflections on the Pilgrimage by Peace Pilgrim.

KT: First I want to respond to your observation about the impact of speed. During the St. Olav Pilgrimage walk, which roughly follows the E6 or actually the other way round, the E6 follows what has been the major throughway from Trondheim to Oslo for hundreds of years, I understood that the E6 is to get people between these two major destinations. Whereas walking on the old roads meant you really went to the town just next to you, and seldom further. Everyone basically stayed put. Why climb the mountain and go over to the next valley? A wedding, a christening, a death. There is a lot of time between those events in a life. Speed as in the ability to get quickly to the desired destination makes the character of the in-between insignificant. And the more insignificant it becomes the more efficient the route is. Walking changes all that. Everything matters, but nothing is exceptional in terms of one needn’t be extra fit, young, etc. I have walked as long as I can remember to think and clear my mind. I lived in the suburbs without a car until I was 16 years old, so I had to walk to the library and school. The monotony of suburban developments was stultifying so the walks didn’t become the walks I had read and heard about, such as the Camino de Santiago, the Appalachian Trail, William Wordsworth walking in the Lake District or Henry David Thoreau walking to and from Walden. Jump ahead a couple of decades and in 2011 I participated in the Walk Exchange’s second class. Two readings really had an enormous impact on me: Walking Meditation by Thich Nhat Hanh and Reflections on the Pilgrimage by Peace Pilgrim.

MA: What is your relationship to meditation, and the use of walking meditation in for example zen buddhism?

KT: A Norwegian friend said walking in Norway is  different than walking in New York City. I walk at least ten kilometers a day in the city, but all the surfaces are hard and there is not much of a grade change. On St. Olav’s Pilgrimage Walk, the planners take you up and down the mountains, through wet moors, and occasionally on a paved bike path or utility road alongside the E6. You walk the terrain with your whole body. When I did the walking meditation with the Walk Exchange following Thich Nhat Hanh’s instructions, I was so sad I wasn’t barefooted. The flatness and stiffness of the ground made it hard for me to walk slowly. On the Pilgrimage walk, my progress was slow. You have to take big steep steps along the mountains, measured steps over slippery roots, jump from rock to rock in wetlands and constantly change in and out of rain protection. I didn’t have to practice my way into full mindfulness. There were other walkers from Germany and Austria who ended up “cheating” and walking along the E6 after they realized it would be faster and less strenuous. The sheer physicality of the walk allowed me to use it as the mantra to be in the studio-walk, as opposed to walking for exercise. To get back to your question, in the Walk Exchange we had to create/design our own walk for the group and then an open walk for the public. I did a walking mediation where we only took right-hand turns, so the mind wasn’t occupied with trying to figure out where one was going. It didn’t go so well. So, I signed up for a Transcendental Mediation initiation and was given my mantra, and meditated with the group in NYC and in LA. I’ve been doing TM ever since and also talk with a fellow artist and friend who follows Thai Forest tradition. She recommended some books which I have read. I am not a practitioner of Buddhism, however, the readings across the many interpretations have been very helpful and I keep reading and talking to practitioners to enrich my understanding. But, my meditation experience actually is physically based. I did Shotokan Karate for five years, Wushu Kung Fu for one and yoga on and off for the last twenty years. All of those physical practices ends with a meditation. I apply all these experiences when I do my studio mediations. I gave students from KHIO a Walking meditation when they were in NYC on a field trip, it went really well this time, and those same students a Looking meditation for a performance of the piece at the Kunstnerforbundet (Oslo). I have also done a Working meditation for the Oslo Open this past April. Walking meditation was an entry point to meditation in a non-sitting position. It is a fundamental that I like to go back to over and over again.

different than walking in New York City. I walk at least ten kilometers a day in the city, but all the surfaces are hard and there is not much of a grade change. On St. Olav’s Pilgrimage Walk, the planners take you up and down the mountains, through wet moors, and occasionally on a paved bike path or utility road alongside the E6. You walk the terrain with your whole body. When I did the walking meditation with the Walk Exchange following Thich Nhat Hanh’s instructions, I was so sad I wasn’t barefooted. The flatness and stiffness of the ground made it hard for me to walk slowly. On the Pilgrimage walk, my progress was slow. You have to take big steep steps along the mountains, measured steps over slippery roots, jump from rock to rock in wetlands and constantly change in and out of rain protection. I didn’t have to practice my way into full mindfulness. There were other walkers from Germany and Austria who ended up “cheating” and walking along the E6 after they realized it would be faster and less strenuous. The sheer physicality of the walk allowed me to use it as the mantra to be in the studio-walk, as opposed to walking for exercise. To get back to your question, in the Walk Exchange we had to create/design our own walk for the group and then an open walk for the public. I did a walking mediation where we only took right-hand turns, so the mind wasn’t occupied with trying to figure out where one was going. It didn’t go so well. So, I signed up for a Transcendental Mediation initiation and was given my mantra, and meditated with the group in NYC and in LA. I’ve been doing TM ever since and also talk with a fellow artist and friend who follows Thai Forest tradition. She recommended some books which I have read. I am not a practitioner of Buddhism, however, the readings across the many interpretations have been very helpful and I keep reading and talking to practitioners to enrich my understanding. But, my meditation experience actually is physically based. I did Shotokan Karate for five years, Wushu Kung Fu for one and yoga on and off for the last twenty years. All of those physical practices ends with a meditation. I apply all these experiences when I do my studio mediations. I gave students from KHIO a Walking meditation when they were in NYC on a field trip, it went really well this time, and those same students a Looking meditation for a performance of the piece at the Kunstnerforbundet (Oslo). I have also done a Working meditation for the Oslo Open this past April. Walking meditation was an entry point to meditation in a non-sitting position. It is a fundamental that I like to go back to over and over again.

MA: Your work (in my eyes) combine two different approaches. They are meditative and your process seem intuitive and wordless. Yet, you also have an academic/intellectual approach in your texts about the works. Could you please tell me about those two different states of minds, and how you work with them?

KT: I think by talking and walking. So, it is important to meet people and then when I’m not with them I’ll «talk» to them when I’m working through an idea (1). It’s great to meet people from anywhere and everywhere so explaining my work to others facilitates meeting people other than the ones I might stumble into at the bar or in the bookstore (2). In my ideal world, everyone is engaged, mindful, and you can have vigorous, thoughtful interactions with anyone and everyone, but too often the people you come across are bogged down by prejudices from their upbringing and are not inclined to go read, for example, every book they can find on sand and why when it is quick it will kill you either fast or slow depending on how much you struggle.

1. There is a huge tangle of thoughts in my head. An existence of another person does a seemingly contradictory thing for my thought process. The conversation with another person stretches the domain of how I’m thinking about something, but the person I «talk» to also gives a path for particular stream of thought to find its way out.

2. Explaining my ideas in what you have deemed an «academic» approach makes my thoughts digestible in the current manifestation of the art world we work in. It seems like every artist is getting a PhD. However, I do have a romantic fantasy about a place where we can live our lives searching for greater understanding of the world around us. Different people use different tools. You would think that academia would be the place for such a pursuit. I am not sure it is. The academy seems to be in a self-replicating mode. But, I like this throw back notion that the philosopher’s greatest tool was poetry…and to wrest material arts out of a purely craft definition and allow it to exist also as a poetic and thus a potential instrument with which to «think». Sadly, the academic voice is given more credence at this moment. If I have opportunities to meet people through invitations to do projects or shows it comes from the ability to write about my work. I usually resist answering in a straight forward way, but since you asked to begin with a remote walk, I thought you could balance the written and the experienced. You would not privilege the text over the lived.

MA: You and I made a ‘remote walk’ a few weeks ago, when you walked for four hours to a friend, starting at 7 in the morning in New York, and I walked simultaneously here in Trondheim, starting at 1 in the afternoon, from Vanvikan to a friend in Stadsbygd. By doing this, you provoked a process in my practice, and I suppose I did too, in yours. What is your relationship to the works/processes the remote walks start in other peoples practices?

MA: You and I made a ‘remote walk’ a few weeks ago, when you walked for four hours to a friend, starting at 7 in the morning in New York, and I walked simultaneously here in Trondheim, starting at 1 in the afternoon, from Vanvikan to a friend in Stadsbygd. By doing this, you provoked a process in my practice, and I suppose I did too, in yours. What is your relationship to the works/processes the remote walks start in other peoples practices?

KT: When you described to me how you needed to change the starting time from 4 PM your time to 1 PM because you would be walking through the woods and it would be dark by 8 PM when you would conclude, the image of you walking along a dark wooded hill flashed in my mind. I carry that picture with me with such glee. It makes me happy to think that we can initiate for each other experiences that is conveyed as an image. Isn’t that what art is? I use devices, or rules to bound a walk to facilitate the “frame” you were speaking of for the walk so that there is room cleared out for reception and integration of external stimuli and internal impulses and predilections. The mantra I gave the students for the Looking meditation performance at Kunstnerforbundet was, “Please make a space.” I told them they literally need to ask the audience to make space for the installation of the piece, but I told them it was like a pebble thrown into the water that makes ripples that reach out. They were asking for a space in the room for the piece and also asking for the space for them in the world to make their work. I like walking because it takes the land back to something experienced as opposed to surveyed for purposes of owning. Doing a remote walk emphasizes the uncertainty because I and the other walker will not have the same experience. It also weakens territoriality. We do not have a corroborative record because we trace two different locations. Another thing I have been thinking about a long time is how explorers and artists are on the vanguard of the wave that colonizes foreign territories such as other countries or distressed neighborhoods. I wanted to find a way to fulfill the need to see what is on the other side of the mountain without fulfilling the function of domesticating land for exploitation. I thought the remote walk was a step in that direction. Pun intended. We walk not in the same place, but we walk together in time. As much as I need and like to work alone, camaraderie makes me and my work stronger.

MA: Isn’t there a danger turning a month of walking into the art work itself? I mean, isn’t the walking a technique for you, basically only an alternative to your normal studio, and a studio is usually not that visible in an art work.

KT: The studio-walk is part of my studio practice  and not an alternative. I need both: to be out in the world not exercising or socializing or getting somewhere, but to think by moving and the room that shelters me and my equipment from inhospitable weather since I make film supplies electricity. When I’m “stuck”, I go for a studio-walk. I forget to be prideful, afraid, anxious, and so I can return to the production studio and take one step in front of the other in the making of something. Sometimes one stumbles, but like on a walk you get up and so what if you come back muddy. There are artists who are less verbal than me, who drew before they could write. They probably don’t need to go on as many studio-walks as I do. I conceptualize, and then execute. It’s also a function of my training as a filmmaker. Film is very costly, so everything has to be planned out. You don’t learn the lessons you get from making when you are always waiting for funding or rewriting to fit into a nonexistent budget. I had to find a method to enable processing my ideas through actual hands-on production. I found it through my studio-walks. Not that walking is a production, but it takes the thoughts in one’s mind and rubs it up against a host of external input. Something you have been looking at in one way and up to then seemingly the only way, suddenly shifts because of observations made on the walk. But with that said, I will be showing my month long walk as a piece at RAKE. It’s also hard to escape art history. The artist in the studio has been a motif in painting since the Renaissance. I created a piece which will not be in the show that is called “Studio Head.” It is a flip book of self-portraits I took during the walk of my head and the landscape behind me. I wanted to place the female artist in the arena of creation like the painter Velazquez in his Las Meninas. Women don’t have to just be muses or objects embodying meaning, they can be depicted as the creators of meaning. So as much as the studio is not visible in most work, the artist and their studio has been a subject for artists for some time now.

and not an alternative. I need both: to be out in the world not exercising or socializing or getting somewhere, but to think by moving and the room that shelters me and my equipment from inhospitable weather since I make film supplies electricity. When I’m “stuck”, I go for a studio-walk. I forget to be prideful, afraid, anxious, and so I can return to the production studio and take one step in front of the other in the making of something. Sometimes one stumbles, but like on a walk you get up and so what if you come back muddy. There are artists who are less verbal than me, who drew before they could write. They probably don’t need to go on as many studio-walks as I do. I conceptualize, and then execute. It’s also a function of my training as a filmmaker. Film is very costly, so everything has to be planned out. You don’t learn the lessons you get from making when you are always waiting for funding or rewriting to fit into a nonexistent budget. I had to find a method to enable processing my ideas through actual hands-on production. I found it through my studio-walks. Not that walking is a production, but it takes the thoughts in one’s mind and rubs it up against a host of external input. Something you have been looking at in one way and up to then seemingly the only way, suddenly shifts because of observations made on the walk. But with that said, I will be showing my month long walk as a piece at RAKE. It’s also hard to escape art history. The artist in the studio has been a motif in painting since the Renaissance. I created a piece which will not be in the show that is called “Studio Head.” It is a flip book of self-portraits I took during the walk of my head and the landscape behind me. I wanted to place the female artist in the arena of creation like the painter Velazquez in his Las Meninas. Women don’t have to just be muses or objects embodying meaning, they can be depicted as the creators of meaning. So as much as the studio is not visible in most work, the artist and their studio has been a subject for artists for some time now.

MA: I understand walking is also an entry point for you to start drawing. You wrote:

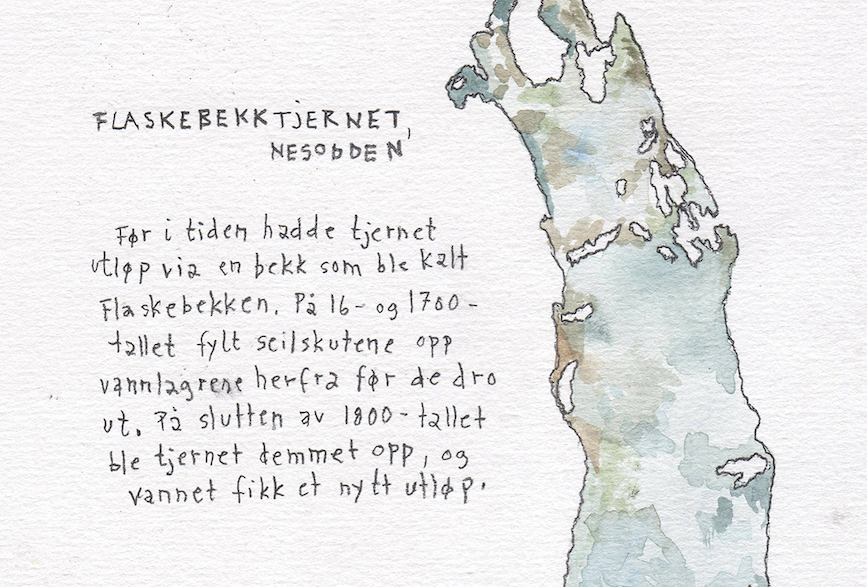

I finally achieved what I had been seeking for a long time…an entry point for me to draw. I am not interested in making drawings, but to draw as a note taking device that tests what I see and how I’m translating it into line and area as opposed to words which my usual notes had consisted of. What I’m describing is the process called abstraction.

Drawing is one of many different abstraction strategies. I have never been able to avail myself of this tool. After a month on my studio-walk, I had found a way to incorporate this skill into my thought process.

Did you have other goals with the walk, and did you reach them?

KT: When I say that an artist in the studio does the work of the studio where everything is at risk, what I mean is I am not in the studio to affirm a party position, contrive to convince someone to buy something they don’t want or need, instead my study is a place for epistemological inquiry. Philosophers approach it through language and logic, visual artists interpret with other tools. So my goal for the studio-walk and the room that holds my tools and “work bench” i.e. my studio, is to understand what I see and express it as knowledge.

Also, I wanted to experience Norway. I spend most of my time in Norway alone in the tower at the Oslo City Hall. I thought it was time for me to see the landscape of this country. Since the walk has been organized to include scenic views, pre-historic hunting ditches, viking burial grounds, churches and preserved farm structures I will be able to have a richer stock by which to understand how little I really know about this country in the short time I have been here. Hopefully, I will be able to make more palpable the need to reach out to someone who is so familiar, we are human after all, but so different by virtue of our history, culture and language.

MA: There is a romantic idea of the walking and strolling man in the landscape; the vagabond, the lonely man in nature. The Norwegian author Tomas Espedal has written a fantastic book called Walk – or the art of living a wild and poetical life. Few authors can get away with such a title, and he writes about his and others walks through different landscapes, and refers to Rosseau etc. His normal walking clothes are suits. Many women, too, has written about walking, for example Rebecca Solnit. What is it like for a woman to be walking alone on the pilgrim route, and other places? What response do you get, are you provoked or provoking something?

KT: It depends where you walk. I have been told that  Tomas Espedal’s book is not yet translated into English. If it had been I would certainly have read it because I’m definitely from the same romantic school as that title. Although, not in the literal sense but more in the literary sense, in that I believe thinking about ideas and expression of ideas in non-verbal ways is living a wild and poetical life. Norway is great for walking alone as a woman. There aren’t a lot of people on the Pilgrim’s Way in August, and the few other walkers you encounter in the majority are women. It was an entirely different story when I was doing the remote walk through Brooklyn when you were walking in Trondheim. There were sections of the road that didn’t have a clear path for walking. It was made for cars. Those sections brought out a lot of honks for myriad reasons. And then there were sections that were only occupied by men working and fishing. You have to negotiate once again a host of cultural hot points: gender, race, class. All of this is obviated in Norway when in a day the only person I meet is the imaginary troll I have conjured up from a very suggestive looking tree stump.

Tomas Espedal’s book is not yet translated into English. If it had been I would certainly have read it because I’m definitely from the same romantic school as that title. Although, not in the literal sense but more in the literary sense, in that I believe thinking about ideas and expression of ideas in non-verbal ways is living a wild and poetical life. Norway is great for walking alone as a woman. There aren’t a lot of people on the Pilgrim’s Way in August, and the few other walkers you encounter in the majority are women. It was an entirely different story when I was doing the remote walk through Brooklyn when you were walking in Trondheim. There were sections of the road that didn’t have a clear path for walking. It was made for cars. Those sections brought out a lot of honks for myriad reasons. And then there were sections that were only occupied by men working and fishing. You have to negotiate once again a host of cultural hot points: gender, race, class. All of this is obviated in Norway when in a day the only person I meet is the imaginary troll I have conjured up from a very suggestive looking tree stump.

MA: You have been curious about the impact on a passerby when seeing a person in a landscape – looking. I have, too. What are your thoughts on it?

KT: Have you seen on those Candid Camera style shows where someone just looks up at something and then the passerby looks up in the same direction. I like the idea of being that pause in the speedway of contemporary life that might make a person wonder what is that person doing that is not just getting somewhere. It feels like a counter consumerist act. If you look at something, and take the time to really see it so that it penetrates you and you know something because of it then you haven’t consumed it, you let it into its being, you don’t stick it in your pocket and commodify it. I think when you are seen looking in the landscape like that, you say, this land is not just in your way or on your way. There is something happening here.

MA: I think your words on what happens during a so called studio-walk could wrap up this interview:

But what really happens on a studio-walk, is that constant movement of stimuli in front of your eyes, in your ears, on your skin and in your body, that the ideas of the mind can get shuffled and sometimes things shake out that reminds you of what you found so moving, inspiring, aggravating in the first place and you may be able to enunciate a plan of action to execute when back in your studio.

NOTE: I was told by Norwegian friends it was a shame that Tomas Espedal wasn’t translated into English. I just looked him up on McNally Jackson, and yes TRAMP: or the art of living a wild and poetical life has been, so I shall pick it up when I return to New York. Looking forward to it.

RAKE, The Moving Studio, Nov. 14th – 30th

KimSu Theiler (USA), Kjell Varvin (NO), Germain Ngoma (Simbabwe, NO), Rus Mesic, Astrid Haugen og Lotte Konow Lund (NO). Curated by Lotte Konow Lund.