Debased in Berlin – Some remarks on art and (cultural) politics

Postkulturell næring, Text Series, Astrid Mania 21.05.2012

Imagine you are a Berlin-based  artist with many needs: financial stability, exhibitions and sales to name a few; but maybe you also long for an in-depth exchange with your peers, a network of sorts. Along comes an “investigation agency”, by the name of S.A.V.E, who inquire about those very needs. You happily and honestly answer their questions (yes, most of you do need money and friends); your statement is duly taken down and filed away in a box. Everybody is welcome to read the results of this survey, but after some weeks the box will be locked and sealed together with your answers, possibly forever; or long enough at least to transform you and your needs into matters of historic and socioeconomic research. It sounds frustrating, doesn’t it?

artist with many needs: financial stability, exhibitions and sales to name a few; but maybe you also long for an in-depth exchange with your peers, a network of sorts. Along comes an “investigation agency”, by the name of S.A.V.E, who inquire about those very needs. You happily and honestly answer their questions (yes, most of you do need money and friends); your statement is duly taken down and filed away in a box. Everybody is welcome to read the results of this survey, but after some weeks the box will be locked and sealed together with your answers, possibly forever; or long enough at least to transform you and your needs into matters of historic and socioeconomic research. It sounds frustrating, doesn’t it?

Or maybe it sounds like the plot of a tragicomic Russian novel about an artist whose dreams and hopes become entangled in public bureaucracy. But no, this scenario describes an artists’ project currently under way at Exile, a commercial gallery in Berlin-Kreuzberg,1initiated by Ambra Pittoni and Paul-Flavien Enriquez-Sarano, aka “Ze Coeupel”. S.A.V.E is at once the name of an on-going performance, and its operating agency. It is not a political initiative or an aid scheme for artists in need, nor does it intend to set up a structure that could provide, for example, a network. More than anything it is, even if unintentionally so, a wonderful metaphor for the exchange between artists and politicians, but also for artistic journeys into the field of cultural politics that never normally make it beyond the stage of representation; it is in fact just such an excursion.

S.A.V.E appears in Berlin at a time when there is a great deal of debate concerning art and politics in the city. This debate, however, is much more alive, persistent and maybe even transformative, than the passive, non-reactive approach S.A.V.E suggests. Discussions were fuelled, if not ignited, by two exhibitions: by based in Berlin, June/July 2011, and the current Berlin Biennale, aptly renamed the “Berlin Biennale for Contemporary Politics”, by its chief curator Artur Żmijewski. Both shows, however, triggered different debates with quite different topics and aims. While based in Berlin started on-going, pragmatic discussions about cultural politics in Berlin, the Berlin Biennale is surrounded by vivid, and controversial discussions about the general role of the artist, and his or her involvement in society and (global) politics.

To understand the fierce opposition that based in Berlin met among large groups within Berlin’s artistic community, it is essential to look at the history and context of the exhibition. The show was decided from above, as a vanity and election campaign project by Berlin’s mayor, Klaus Wowereit, who was at the time also in charge of culture. It was meant as a contribution to a discussion that was by then, basically over: did Berlin need a permanent Kunsthalle? In August 2010, the Temporäre Kunsthalle had closed and was later dismantled after its scheduled lifespan of two years had expired. Wowereit, with an eye on the visual arts loving electorate, pushed for a permanent Kunsthalle, against the will of his own party.2As the title suggests, based in Berlin was conceived as an overview of Berlin’s young contemporary art scene. It was given, for Berlin standards, an outrageous budget of 1.4 million Euros, with almost one million of that coming from the German Lottery Foundation.3 Many felt that this money should have been spent on the existing, struggling art institutions or smaller-scale and independent artistic endeavours.

To understand the fierce opposition that based in Berlin met among large groups within Berlin’s artistic community, it is essential to look at the history and context of the exhibition. The show was decided from above, as a vanity and election campaign project by Berlin’s mayor, Klaus Wowereit, who was at the time also in charge of culture. It was meant as a contribution to a discussion that was by then, basically over: did Berlin need a permanent Kunsthalle? In August 2010, the Temporäre Kunsthalle had closed and was later dismantled after its scheduled lifespan of two years had expired. Wowereit, with an eye on the visual arts loving electorate, pushed for a permanent Kunsthalle, against the will of his own party.2As the title suggests, based in Berlin was conceived as an overview of Berlin’s young contemporary art scene. It was given, for Berlin standards, an outrageous budget of 1.4 million Euros, with almost one million of that coming from the German Lottery Foundation.3 Many felt that this money should have been spent on the existing, struggling art institutions or smaller-scale and independent artistic endeavours.

The most prominent and articulate movement in opposition to based in Berlin, was Haben und Brauchen, initiated and facilitated by curator Ellen Blumenstein and artist/curator Florian Wüst.4 In an open letter from January 25, 2011, Haben und Brauchen demanded amongst other things, a revision of the exhibition’s concept, and public discussions about “how the production and presentation conditions of contemporary art in Berlin can be sustainably supported and developed away from media beacons.”5 Still, based in Berlin was, “a symptom, not the enemy”, as Ellen Blumenstein points out.6Haben und Brauchen did not prevent or alter based in Berlin; the success of this initiative manifests itself in on-going discussions about the “disease”, if you like, the cause of the symptoms. This debate still continues, now in smaller, independent working groups as well as in conversations with politicians, and apparently, they have born some results. The 2011 coalition contract between the two ruling parties in Berlin, currently the Social Democratic Party and the Christian Democratic Union, stipulates “a dialogue about the future of the visual arts in Berlin”.7 The preparation of such a dialogue, in the form of a workshop, is now underway according to Ingrid Wagner, deputy head for cultural affairs in the Senate Chancellery of Berlin. The Senate Committee for Culture, she says, was interested in hearing what Berlin’s creative scene is thinking and saying, and this she attributes directly to the debates that surrounded based in Berlin.

The most prominent and articulate movement in opposition to based in Berlin, was Haben und Brauchen, initiated and facilitated by curator Ellen Blumenstein and artist/curator Florian Wüst.4 In an open letter from January 25, 2011, Haben und Brauchen demanded amongst other things, a revision of the exhibition’s concept, and public discussions about “how the production and presentation conditions of contemporary art in Berlin can be sustainably supported and developed away from media beacons.”5 Still, based in Berlin was, “a symptom, not the enemy”, as Ellen Blumenstein points out.6Haben und Brauchen did not prevent or alter based in Berlin; the success of this initiative manifests itself in on-going discussions about the “disease”, if you like, the cause of the symptoms. This debate still continues, now in smaller, independent working groups as well as in conversations with politicians, and apparently, they have born some results. The 2011 coalition contract between the two ruling parties in Berlin, currently the Social Democratic Party and the Christian Democratic Union, stipulates “a dialogue about the future of the visual arts in Berlin”.7 The preparation of such a dialogue, in the form of a workshop, is now underway according to Ingrid Wagner, deputy head for cultural affairs in the Senate Chancellery of Berlin. The Senate Committee for Culture, she says, was interested in hearing what Berlin’s creative scene is thinking and saying, and this she attributes directly to the debates that surrounded based in Berlin.

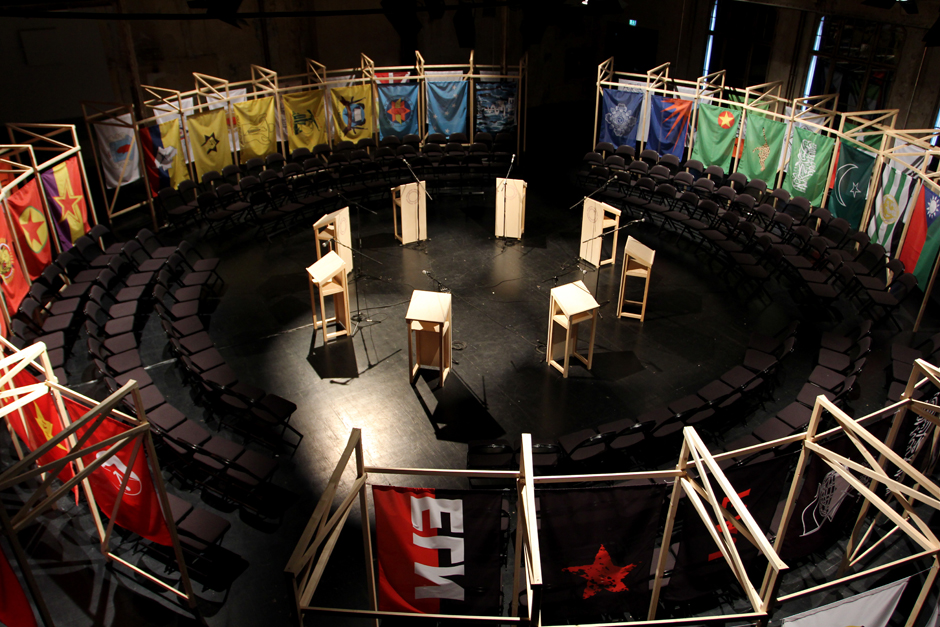

The discussions about art and politics that Artur Żmijewski kicked off, took a different direction right from the outset. As early as November 2010, Żmijewski initiated an open call; artists were invited to become part of the biennale’s research process and to send in material related to their work. Moreover, participants were asked to inform the biennale about their “political inclination, e.g. rightist, leftist, liberal, nationalist, anarchist, feminist, or whatever persuasion they identified themselves with, if any at all.”8 Even though this direct inquiry into an individual’s political beliefs caused some controversy, quite a large number of artists provided answers – they are visually displayed in the context of the biennale, but not commented upon or processed in any other way.9

The biennale’s P/Act for Art,  one of the many projects and discussions preceding the exhibition, speaks of a similar approach and leaves another lively debate somewhat unfinished and unresolved. In September 2011, a newspaper-style publication with: Statements on cultural policy and a proposal by the 7th Berlin Biennale was issued, comprising texts by some 50 (mostly) Berlin-based artists, curators, dealers and collectors. They had responded to Żmijewski’s scheme to establish a written “social contract” between art and politics. Besides asking after the political and social responsibilities of an artist, Żmijewski demanded a written “constitution” that would lay down respect for artists and curators and allow for transparency when it comes to the distribution of the profits generated by culture. This collection of opinions and propositions with specific regards to the situation of cultural politics in Berlin has no further resonance in the biennale itself. Talks between the biennale organisers and members of Haben und Brauchen, for instance, did not lead to a joint venture. The facilitators of Haben und Brauchen felt as if they were: “restaging a debate that had already moved on”.10 Moreover, “the discursive processes that mark the approach of Haben und Brauchen and aim for long-lasting effects, do not fit into Żmijewski’s activist model of thought”, as Dorothee Albrecht and Ludwig Seyfarth so accurately conclude in their comment on the Berlin Biennale.11

one of the many projects and discussions preceding the exhibition, speaks of a similar approach and leaves another lively debate somewhat unfinished and unresolved. In September 2011, a newspaper-style publication with: Statements on cultural policy and a proposal by the 7th Berlin Biennale was issued, comprising texts by some 50 (mostly) Berlin-based artists, curators, dealers and collectors. They had responded to Żmijewski’s scheme to establish a written “social contract” between art and politics. Besides asking after the political and social responsibilities of an artist, Żmijewski demanded a written “constitution” that would lay down respect for artists and curators and allow for transparency when it comes to the distribution of the profits generated by culture. This collection of opinions and propositions with specific regards to the situation of cultural politics in Berlin has no further resonance in the biennale itself. Talks between the biennale organisers and members of Haben und Brauchen, for instance, did not lead to a joint venture. The facilitators of Haben und Brauchen felt as if they were: “restaging a debate that had already moved on”.10 Moreover, “the discursive processes that mark the approach of Haben und Brauchen and aim for long-lasting effects, do not fit into Żmijewski’s activist model of thought”, as Dorothee Albrecht and Ludwig Seyfarth so accurately conclude in their comment on the Berlin Biennale.11

The debate that Żmijewski and his associated curators, Joanna Warsza and The Voina Group started is of a different kind than the small-scale, small-step, pragmatic approaches of initiatives like Haben und Brauchen. The biennale calls for art that is a tool for change, if not salvation. “The concept of the 7th Berlin Biennale is quite straightforward and can be condensed into a single sentence: we (…) present art that actually works, makes its mark on reality, and opens a space where politics can be performed.”12 But the presentation of this kind of art – and in this biennale, a lot of it is “imported” from places with rigid political systems, Belarus for example – reduces the artistic or activist interventions to re-presentations and illustrations of the romantic/religious ideals of the curator(s).

The notion of art that “works” – in the German translation of this word, “works” reads as “wirksam”, or “effective” – comes with more than just a a hitch. The biennale’s distinctive outlook on art and the role it should play in society gives ammunition to all those who advocate the autonomy of art, in opposition to art that is, willingly, or unwillingly, instrumentalised by politics; a road we do not need to go down. What is precarious about Żmijewski’s insistence on an art that has political and social agency, within the context of a neoliberal democracy, is the resonance his vocabulary has with neoliberal concepts of usefulness and evaluation. Because of the city’s disastrous financial situation, Berlin’s (and, of course, many other city’s) institutions find themselves under growing pressure to justify their existence by increasing visitor numbers. This situation was aggravated after the blockbuster show “Das MoMA in Berlin” (2004) attracted about 1.2 million visitors, due to an unprecedented PR campaign and the allure of New York’s beacon of modern art. The current exhibition programme of Berlin’s Hamburger Bahnhof – Museum für Gegenwart, with highlights like the Carsten Höller and Tomás Saraceno exhibitions13 (a laboratory-cum-art-installation involving reindeer and canary birds for the former, and float-on transparent bubbles disguised as socio-architectural utopia, from the latter), are showcases for this tendency. In a city and a society that is struggling to justify cultural budgets,14 that is more and more willing to subject culture to the logic of supply and demand, any suggestion towards art that is effective must sound alarming. It is almost tragic that with his call for political art, Żmijewski might actually strengthen the very system he so passionately fights.15 Still, we talk a lot about art and politics in Berlin these days. And some of us even act.

The notion of art that “works” – in the German translation of this word, “works” reads as “wirksam”, or “effective” – comes with more than just a a hitch. The biennale’s distinctive outlook on art and the role it should play in society gives ammunition to all those who advocate the autonomy of art, in opposition to art that is, willingly, or unwillingly, instrumentalised by politics; a road we do not need to go down. What is precarious about Żmijewski’s insistence on an art that has political and social agency, within the context of a neoliberal democracy, is the resonance his vocabulary has with neoliberal concepts of usefulness and evaluation. Because of the city’s disastrous financial situation, Berlin’s (and, of course, many other city’s) institutions find themselves under growing pressure to justify their existence by increasing visitor numbers. This situation was aggravated after the blockbuster show “Das MoMA in Berlin” (2004) attracted about 1.2 million visitors, due to an unprecedented PR campaign and the allure of New York’s beacon of modern art. The current exhibition programme of Berlin’s Hamburger Bahnhof – Museum für Gegenwart, with highlights like the Carsten Höller and Tomás Saraceno exhibitions13 (a laboratory-cum-art-installation involving reindeer and canary birds for the former, and float-on transparent bubbles disguised as socio-architectural utopia, from the latter), are showcases for this tendency. In a city and a society that is struggling to justify cultural budgets,14 that is more and more willing to subject culture to the logic of supply and demand, any suggestion towards art that is effective must sound alarming. It is almost tragic that with his call for political art, Żmijewski might actually strengthen the very system he so passionately fights.15 Still, we talk a lot about art and politics in Berlin these days. And some of us even act.

1 http://www.thisisexile.com/project_GoranTomcicZeCoeupel.html

2 By mid-July 2011, the then red-red Berlin Senate (Social Democratic Party and The Left) decided on the budget for 2012/13 that did not provide the necessary means for a permanent Kunsthalle. Cf. http://www.goethe.de/kue/bku/kuw/de7978518.htm.

3 The self-description of the foundation reads as follows: “The foundation ‘Stiftung Deutsche Klassenlotterie Berlin’ is a legal foundation of public law based in Berlin. The foundation supports projects in Berlin, for Berlin institutions or projects that are of special interest for Berlin. It exclusively pursues non-profit purposes supporting social, charitable, cultural and civic plans as well as projects that deal with environmental protection, sports and the promotion of young people with donations.” Cf. http://www.creative-city-berlin.de/en/institution/stiftung-deutsche-klassenlotterie-berlin/

4 http://www.habenundbrauchen.de/

5 http://www.bbk-berlin.de/con/bbk/front_content.php?idart=826

6 Ellen Blumenstein in a conversation with the author, Berlin, May 13, 2011.

7 http://www.berlin.de/imperia/md/content/rbm-skzl/koalitionsvereinbarung/koalitionsvereinbarung_2011.pdf, p. 94

8 http://www.berlinbiennale.de/blog/en/projects/open-call-artwiki-digital-venue-of-the-7th-berlin-biennale-for-contemporary-art-18348

9 Burak Arikan transformed the results into a “network map of artists and political inclinations” that is both on display at Kunst-Werke Berlin and online: http://burak-arikan.com/network-map-of-artists-and-political-inclinations-7th-berlin-biennale

10 Ellen Blumenstein in conversation with the author, Berlin, May 13, 2011.

11 http://www.artnet.de/magazine/kommentar-zur-7-berlin-biennale/, transl. by A.M.

12 Artur Żmijewski, Foreword, in: Berlin Biennale Zeitung, Act for Art – Forget Fear, p. 6, italics in the original.

13 Carsten Höller: “Soma”, November 5, 2010 – February 6, 2011 and Tomás Saraceno: “Cloud Cities”, September 15, 2011 – February 19, 2012.

14 Recently, four prominent protagonists of German culture published their book “Der Kulturinfarkt” (The Collapse of Culture) in which they call for a radical cut in the number of public theatres and museums in Germany. Dieter Haselbach, Armin Klein, Pius Knüsel: Der Kulturinfarkt. Von Allem zu viel und überall das Gleiche. Eine Polemik über Kulturpolitik, Kulturstaat, Kultursubvention, Albrecht Knaus Verlag, 2012.

15 In his contribution to „(P)Act for Art“, he states: “As usual, it is depoliticized culture that falls prey to those who are more efficient in playing the game of power.” And: “Art that would be devoid of politics is an illusion, a dangerous mirage perpetuated by the artists themselves. Repressing the politics is a mistake, because the repressed always returns, most often as a nightmare.” Artur Żmijewski: “(P)Act for Art”, in: P/Act for Art, Statements on Cultural Policy and a Proposal by the 7th Berlin Biennale, 7. Berlin Biennale Zeitung, Berlin 2011, pp. 4/5