Third Wave Privatisation of Cultural Provision in the UK

Postkulturell næring, Text Series, Rebecca Gordon-Nesbitt 09.10.2011

First Wave

A few months  before the 1979 UK general election, Margaret Thatcher promised the Chairman of the Arts Council that her government would continue to support the arts. But once elected, she cut spending in all areas of public policy, and the cultural field was no exception. Thatcher’s belief was that the obsolete system of arts patronage should not be compensated for solely by the state, and she appointed Norman St John-Stevas as Arts Minister, who argued that the private sector must be looked to for new sources of funding. Accordingly, the new government reduced arts expenditure in its first budget by £3 million (out of a total £63 million) and quickly launched a campaign aimed at doubling the 1979 figure for private sponsorship of £3-4 million. St John-Stevas established a fourteen-member sponsorship committee which naturally included corporate executives, and tax relief was offered to businesses supporting the arts. A special grant was made to the Association of Business Sponsorship of the Arts, whose role it was to broker deals between corporate sponsors and cultural institutions, and a tirade was launched against the ‘welfare state mentality’ that the government perceived to exist among arts organisations.

before the 1979 UK general election, Margaret Thatcher promised the Chairman of the Arts Council that her government would continue to support the arts. But once elected, she cut spending in all areas of public policy, and the cultural field was no exception. Thatcher’s belief was that the obsolete system of arts patronage should not be compensated for solely by the state, and she appointed Norman St John-Stevas as Arts Minister, who argued that the private sector must be looked to for new sources of funding. Accordingly, the new government reduced arts expenditure in its first budget by £3 million (out of a total £63 million) and quickly launched a campaign aimed at doubling the 1979 figure for private sponsorship of £3-4 million. St John-Stevas established a fourteen-member sponsorship committee which naturally included corporate executives, and tax relief was offered to businesses supporting the arts. A special grant was made to the Association of Business Sponsorship of the Arts, whose role it was to broker deals between corporate sponsors and cultural institutions, and a tirade was launched against the ‘welfare state mentality’ that the government perceived to exist among arts organisations.

This account is taken from Chin-tao Wu’s examination of the corporate takeover of the arts in the US and the UK. 1 She details how members of parliament on the right wing of Thatcher’s Conservative Party had called for the total abolition of its cultural funding body, the Arts Council of Great Britain (ACGB). Understanding that this would cause resistance, the government decided that, rather than scrapping the council, it would implement its policies through the existing organisation by appointing politically-aligned chairmen to reshape the council.2 This undermined the arm’s length principle that had prevented government intervention into arts funding, and called into question the idea that access to the arts was a democratic right, which qualified them to receive public funding.

Throughout the 1980s, ACGB was compelled to advocate private support (specifically business sponsorship), and prevailed upon to write to its core-funded organisations outlining new business ideas. Museums were exposed to market forces and forced to become more enterprising, while Conservative businessmen were appointed to their boards. This ‘harnessing of the power of corporate capital into what had hitherto, at least in Britain, been an almost exclusively public domain’3 meant that arts organisations found themselves competing with each other to attract sponsorship.

During this time, the corporate approach to sponsoring the arts moved from the passive provision of solicited donations to the proactive deployment of funds as part of a targeted public relations strategy. This became part of a two-pronged attack which either made a connection between the brand and exhibition – exemplified by the distribution of a drinks manufacturer’s product at a private view – or aimed to improve the corporate image, which proved especially useful for companies whose brands (alcohol, tobacco, oil or armaments) were in need of burnishing in the public eye. In turn, this marked a shift from a ‘something for nothing’ attitude to a climate of ‘something for something’,4 in which sponsors often demanded lavish receptions at which they could entertain their guests, providing them with a seemingly apolitical space in which politicians could be met and lobbied.

During this time, the corporate approach to sponsoring the arts moved from the passive provision of solicited donations to the proactive deployment of funds as part of a targeted public relations strategy. This became part of a two-pronged attack which either made a connection between the brand and exhibition – exemplified by the distribution of a drinks manufacturer’s product at a private view – or aimed to improve the corporate image, which proved especially useful for companies whose brands (alcohol, tobacco, oil or armaments) were in need of burnishing in the public eye. In turn, this marked a shift from a ‘something for nothing’ attitude to a climate of ‘something for something’,4 in which sponsors often demanded lavish receptions at which they could entertain their guests, providing them with a seemingly apolitical space in which politicians could be met and lobbied.

Multinational companies began to involve themselves in the direct sponsorship of exhibitions and in giving awards to artists. In the case of the Institute of Contemporary Arts (ICA) in London, the Beck’s Futures prize was deliberately aimed at emerging artists and their youthful friends and involved the hearty consumption of a certain German beer at launch events. This followed a three-year sponsorship of the ICA by Toshiba, which had seen the electronics giant’s logo appearing on all publicity material, and the company’s gadgets being prominently displayed in the gallery’s foyer. Julian Stallabrass outlines ‘the explicit aim of the Conservative government led by Margaret Thatcher to transform the uncomfortably political character of contemporary art by making it more dependent on market forces’.5

Second Wave

Quarter of a century later, Bourdieu would observe, with regret, towards the end of his life, that ‘what is currently happening to the universes of artistic production throughout the developed world is entirely novel and truly without precedent: the hard won independence of cultural production and circulation is being threatened, in its very principle, by the intrusion of commercial logic at every stage’.6 Aside from corporate intervention into the arts at museum level, the private market for art had been growing in parallel with the development of finance capitalism since the stock market crash of 1989, leaving the UK accounting for around a quarter of the global market.

In 1991, seven years before a commercial market for post-conceptual art was created in Scotland, Glasgow-based artist, Ross Sinclair, observed that the market denied art its social role:

When the context of art dissolves into the realm of formalism and the art world exclusively, it has relinquished much of its potential for social function. It loses an important dimension and diminishes from a potentially rounded, holistic art practice and becomes a two-dimensional veneer. Then its meaning and location exists primarily for the market and the cultural activity, Art, ceases to have a wider social function other than in matters of economics.7

Indeed, the prevalence  of the art market leads to a situation in which ‘artists, for all their predilection for anti-establishment and anti-bourgeois rhetoric, [spend] much more energy struggling with each other and against their own traditions in order to sell their products than they [do] engaging in real political action’.8 In this way, the market adopts an ideological function and the main point at which art and life collide is within the market economy, which renders art subordinate to capital and invalidates any claim to even partial autonomy. The potency of the market and the competitiveness it engenders means that many artistic investigations are driven by financial considerations, and Peter Bürger argues that what we have witnessed in recent decades is ‘the total subordination of work contents to profit motives, and a fading of the critical potencies of works in favour of a training in consumer attitudes’.9 As is well known, in 1990s London this spawned a generation of young British artists who demonstrated ‘a lack of critique, except in defined and controlled circumstances’.10

of the art market leads to a situation in which ‘artists, for all their predilection for anti-establishment and anti-bourgeois rhetoric, [spend] much more energy struggling with each other and against their own traditions in order to sell their products than they [do] engaging in real political action’.8 In this way, the market adopts an ideological function and the main point at which art and life collide is within the market economy, which renders art subordinate to capital and invalidates any claim to even partial autonomy. The potency of the market and the competitiveness it engenders means that many artistic investigations are driven by financial considerations, and Peter Bürger argues that what we have witnessed in recent decades is ‘the total subordination of work contents to profit motives, and a fading of the critical potencies of works in favour of a training in consumer attitudes’.9 As is well known, in 1990s London this spawned a generation of young British artists who demonstrated ‘a lack of critique, except in defined and controlled circumstances’.10

As we have seen, public funding for the arts, which might once have funded controversial work, was diminishing during that period. One might expect that the arts councils of England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland (into which ACGB was subdivided in the mid-1990s) would have tried to resist the marketisation of art. But, as had been the case with corporate sponsorship, the turn towards the market was aided and abetted by public funding bodies, which launched interest-free loans to subsidise art collecting. In 2004, Arts Council England, commissioned a report from private consultants called Taste Buds: how to cultivate the art market. This document unequivocally placed the flourishing private market at the centre of the art system and examined how it could be better exploited, identifying 6.1 million potential collectors of contemporary art.11 In the process, all activities in what was traditionally regarded as the public sphere – from art school and artist-led activity to public gallery – are rendered subordinate to the market, failing to take proper account of the intentions of art pitted against neoliberalism. Reflecting the relationship between nation states and multinational capital, the distinction between public and private was irrevocably eroded.

Third Wave

Emphasis on private sponsorship has continued into the Conservative-Liberal Democrat coalition, re-emerging as a return to patronage and philanthropy, while the market is enthusiastically promoted alongside the creative industries that are touted as the key to economic salvation.12 Over the past four years in Scotland, we have been witnessing a third wave in the privatisation of cultural provision. While the main public funding body south of the border was being compromised from within, the cultural department of the largest local authority, Glasgow City Council – which has a virtual monopoly over museums and libraries in the city – was being privatised.

Emphasis on private sponsorship has continued into the Conservative-Liberal Democrat coalition, re-emerging as a return to patronage and philanthropy, while the market is enthusiastically promoted alongside the creative industries that are touted as the key to economic salvation.12 Over the past four years in Scotland, we have been witnessing a third wave in the privatisation of cultural provision. While the main public funding body south of the border was being compromised from within, the cultural department of the largest local authority, Glasgow City Council – which has a virtual monopoly over museums and libraries in the city – was being privatised.

Just before Tony Blair’s former Scottish counterpart, Jack McConnell, was submerged by the political sea change of May 2007, his wife, Bridget, was rushing decisions through Glasgow’s council chambers at unprecedented speed in her capacity as Executive Director of Cultural and Leisure Services. The results of her hurried endeavours was the creation of a new double-headed company, known as Culture and Sport Glasgow (CSG), which would thenceforth substitute the functions of her former council department.

At that time, the leader of the Labour-dominated council had enthusiastically underwritten the devolution of the profitable functions of the council to twelve newly created companies that would be overseen by his political allies.13 In general, it was argued that these arm’s length external organisations (ALEOs) would create £7 million for the people of Glasgow (in fact, they have lost around £5 million).14 In the field of culture, alongside such projected savings, the rationale was that autonomous status would enable additional sources of funding, such as the national lottery, to be plumbed, introducing a new player into an already competitive fundraising arena.

From the outset, serious concerns were raised about the devolution of cultural provision in the city to a private company.15 In the first place, there were well-founded fears that the fundraising hopes of CSG were inflated, since ‘Findings show that many such trusts suffer funding problems as council support is phased out, while private donations either fail to materialise or do not consistently deliver the funding required to maintain services’.16 The service fee paid to CSG by Glasgow City Council under the devolved arrangement only accounts for nine months’ worth of funding and the rest must be raised from external sources in order for the full complement of services to be provided.17 If the company fails to attract this external funding, the facilities it operates and the people using them will suffer. In autumn 2009, CSG was informed that the service fee payable by Glasgow City Council was to be reduced by an initial £1.7 million p.a.,18 likely to increase over the following three years.19 This state of affairs was reported to the CSG board at the September 2009 meeting and, rather than concentrating on ways to plug this already substantial shortfall, Bridget McConnell outlined a need for further savings on the basis of rising utility costs and pension contributions and reduced income forecasts.20 By the time of the next board meeting, in November 2009, this revision of spending had translated into ‘a strategy for reducing Culture and Sport Glasgow’s expenditure by £3.4m for 2010/11’,21 thus doubling the cuts imposed by the loss of council funding. It is worth mentioning that, during the September 2010 board meeting, an even worse prognosis was given, which took into account the likelihood that the Scottish Government would also decide to ‘protect key service areas which would inevitably mean much larger cuts for the organisation’.22 No longer falling under the auspices of the public sector, CSG has no protection when the national government considers its key service areas.

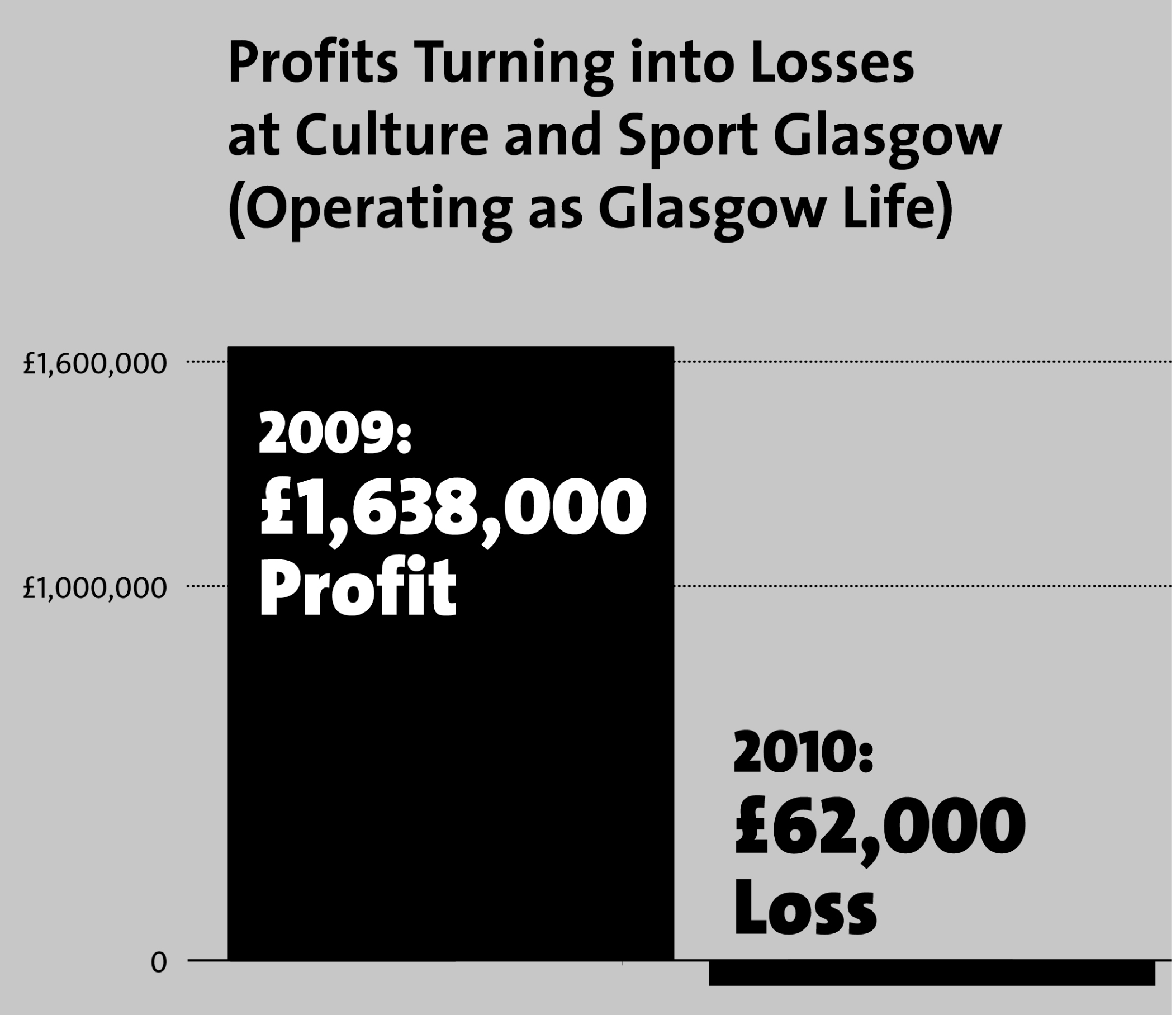

Turning to a consideration  of the external funding that it was envisaged would plug this gap, as one might expect in the current economic climate, grant income has taken a serious battering, dropping from £7.1 million in 2008-9 to £3.1 million in 2009-10. The net return on unspecified investments is also down, by more than £500,000,23 contributing to a decrease in the overall voluntary income into the group of £3.2 million.24 The pension deficit has also grown exponentially, reaching £58.1 million by the end of the 2010 financial year. Considering all ordinary activities carried out by CSG before taxation at 31 March 2010, Glasgow City Council reported a loss of £1.399 million compared to a profit of £1.638 million in the previous financial year – a gap of £3 million overall.25 This dire financial position might well lead the company into unsavoury collaborations with the private sector as already evinced by the sponsorship of the Riverside Museum by BAE Systems, Britain’s favourite arms dealer.26

of the external funding that it was envisaged would plug this gap, as one might expect in the current economic climate, grant income has taken a serious battering, dropping from £7.1 million in 2008-9 to £3.1 million in 2009-10. The net return on unspecified investments is also down, by more than £500,000,23 contributing to a decrease in the overall voluntary income into the group of £3.2 million.24 The pension deficit has also grown exponentially, reaching £58.1 million by the end of the 2010 financial year. Considering all ordinary activities carried out by CSG before taxation at 31 March 2010, Glasgow City Council reported a loss of £1.399 million compared to a profit of £1.638 million in the previous financial year – a gap of £3 million overall.25 This dire financial position might well lead the company into unsavoury collaborations with the private sector as already evinced by the sponsorship of the Riverside Museum by BAE Systems, Britain’s favourite arms dealer.26

Since the creation of CSG, it has also been consistently anticipated that the effective privatisation of the city’s cultural and leisure provision would have a detrimental impact both on those working in the field and on the long-term financial viability of the city’s facilities. In response to the declining financial picture outlined above, CSG proposed major cuts in precisely these two areas, suggesting a review of staff terms and conditions and of the venues that it operates. The first of these controversial processes has resulted in reductions to holidays, working hours and overtime. This has been strongly resisted through combined strike action by members of the four main employment unions involved and necessitated a conciliation process overseen by the man who presided over the Northern Irish peace agreement.

The second of the significant cost-cutting measures explored by CSG resulted in recommendations to close eleven of the recreation and community centres it operates, some of them in parts of a city found to have the lowest levels of life expectancy.27 Fortunately, these proposals needed to be ratified by the full council, which rejected the closure of facilities and venues operated by CSG.28In this way, a democratically elected group of officials accountable to the people was able to overturn the recommendations of a private entity, but the issue has not disappeared from the agenda.

Another abiding concern has been that the new structure would simultaneously diminish transparency and accountability and increase in opportunities for private gain.

Another abiding concern has been that the new structure would simultaneously diminish transparency and accountability and increase in opportunities for private gain.  Derision of ALEOs over the payment of councillors to attend board meetings, which effectively saw the leader’s favourites being paid twice for their time,29 has grown in the wake of said leader’s dramatic fall from grace under a cocaine cloud and alleged links to organised crime.30 CSG is controlled by a handful of political appointees alongside various bankers and businessmen, a public relations expert and an intellectual property lawyer, with little expertise in the arts beyond their own flawed connoisseurship.31 The company’s quasi-autonomous status provides ample scope for its directors to profit from an association with culture. Having overseen the renovation of the Kelvingrove Museum, one of CSG’s independent directors, the octogenarian, Lord Macfarlane, for example, was instrumental in organising an exhibition of paintings by The Glasgow Boys, of which he is a significant collector, thus boosting the provenance (and value) of the artworks he owns. Even more tangible was the connection between another independent director, the businessman, Sir Angus Grossart, and the lucrative re-branding of CSG less than two years after it was established. A flawed procurement process saw an Edinburgh-based consultancy in which Grossart has a financial interest being appointed to oversee the company’s name-change to Glasgow Life. Yet, while Grossart nobly declared his interest at CSG board meetings, he failed to do so where it mattered – in the accounts submitted to Companies House – which represents a serious breach of public trust, not to mention legality.32

Derision of ALEOs over the payment of councillors to attend board meetings, which effectively saw the leader’s favourites being paid twice for their time,29 has grown in the wake of said leader’s dramatic fall from grace under a cocaine cloud and alleged links to organised crime.30 CSG is controlled by a handful of political appointees alongside various bankers and businessmen, a public relations expert and an intellectual property lawyer, with little expertise in the arts beyond their own flawed connoisseurship.31 The company’s quasi-autonomous status provides ample scope for its directors to profit from an association with culture. Having overseen the renovation of the Kelvingrove Museum, one of CSG’s independent directors, the octogenarian, Lord Macfarlane, for example, was instrumental in organising an exhibition of paintings by The Glasgow Boys, of which he is a significant collector, thus boosting the provenance (and value) of the artworks he owns. Even more tangible was the connection between another independent director, the businessman, Sir Angus Grossart, and the lucrative re-branding of CSG less than two years after it was established. A flawed procurement process saw an Edinburgh-based consultancy in which Grossart has a financial interest being appointed to oversee the company’s name-change to Glasgow Life. Yet, while Grossart nobly declared his interest at CSG board meetings, he failed to do so where it mattered – in the accounts submitted to Companies House – which represents a serious breach of public trust, not to mention legality.32

While the situation outlined in this section is based on a detailed investigation into the mis-managed affairs of Culture and Sport Glasgow (a.k.a. Glasgow Life), we should not forget the ideological impetus underlying third wave privatisation. The UK has been proud to follow the US along the uncharted tunnel of capitalist globalisation (a.k.a. neoliberalism), which valorises the free market and demonises the state. Predicated on outdated notions of the creative city and cultural tourism, the Glasgow case demonstrates the inevitable effects of this logic in microcosm, prioritising the presumed wants of visitors to the city over the real needs of its impoverished citizens and allowing private interests to triumph over public gain.

-

Chin-tao Wu, Privatising Culture: Corporate Art Intervention since the 1980s (London: Verso, 2002).

-

The ardent Tory supporter, Sir William Rees-Mogg, was appointed in 1982 and the developer, Lord Peter Palumbo, in 1989.

-

Wu, op cit., p.47.

-

This was well documented by Anthony Davies and Simon Ford in their trilogy of texts, Art Capital, Art Futures and Culture Clubs (see www.infopool.org.uk).

-

Julian Stallabrass, Art Incorporated: The Story of Contemporary Art (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004), p. 134.

-

Pierre Bourdieu, ‘Culture is in Danger’ in Firing Back: Against the Tyranny of the Market (London: Verso, 2003), p.67.

-

Ross Sinclair, ‘Questions’ in Windfall (Glasgow, 1991).

-

David Harvey, The Condition of Postmodernity: An Enquiry into the Origins of Cultural Change (Oxford: Blackwell, 1980), p. 22.

-

Peter Bürger, The Theory of the Avant-Garde (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1984 [1974]), p. 30.

-

Stallabrass, op cit., p. 136.

-

Morris Hargreaves McIntyre, Taste Buds: How to cultivate the art market (London: Arts Council England, October, 2004).

-

In his first major speech as Prime Minister, on 28 May 2010, David Cameron identified a key part of rebalancing the economy to reside in support for knowledge-based industries, including the creative industries. See http://www.number10.gov.uk/news/transforming-the-british-economy-coalition-strategy-for-economic-growth/ Defined as ‘those industries which have their origin in individual creativity, skill and talent and which have a potential for wealth and job creation through the generation and exploitation of economic property’, this has largely excluded visual art. See Department for Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS), Creative Industries Economic Estimates, 9 December 2010.

-

Glasgow City Council has formed subsidiaries companies with a 99.99% share holding. These companies are City Building (Glasgow) LLP, City Building (Contracts) LLP, City Parking LLP, City Property Glasgow LLP, Cordia services LLP, Cordia care LLP and City Markets Glasgow LLP. The remaining 0.01% share holding of these companies is owned by Glasgow City Council LLP Investments Ltd which is 100% owned by Glasgow City Council. Glasgow City Council also holds 90.87% of the shares in the Scottish Exhibition Centre. For completeness the following companies have no shares but Glasgow City Council has 100% membership of the companies – Culture & Sport Glasgow, Glasgow City Marketing Bureau and Glasgow Clyde Regeneration Ltd. Glasgow City Council also has 67% interest in Glasgow Cultural Enterprises Ltd. Taken from a Freedom of Information request.

-

David Leask, ‘Glasgow’s crumbling Aleos empire’, The Herald, 16 June 2010.

-

See Rebecca Gordon-Nesbitt, ‘The New Bohemia’, Variant, Vol. 2, 32, summer 2008, pp. 5-8 http://www.variant.org.uk/pdfs/issue32/Variant32RGN.pdf

-

‘O Rose, thou art sick! Outsourcing Glasgow’s Cultural & Leisure Services’, Variant, issue 29, summer 2007, p. 30.

-

See Culture and Sport Glasgow Ltd Report and Group Financial Statements 31 March 2010 (held at Companies House), p. 12.

-

See Report by the Chief Executive on Budget and Service Planning, note 9(2)(a) of a Minute of a Meeting of the Board of Directors of Culture and Sport Glasgow, 2nd September 2009 and Budget Plan 2010/11, Report to Board Meeting of 31 March 2010 by Interim Director of Finance, point 6. In the unaudited version of Glasgow City Council’s accounts to 31 March 2010, inspected under the provision of the Local Authority Accounts (Scotland) Regulations 1985, the service fee payable to CSG by GCC is given as £72.765 million. In the Report and Group Financial Statements for Culture and Sport Glasgow Ltd, it is given as £76.149 million.

-

This is stated in a letter from the Director of Strategic Planning and Corporate Services at CSG, dated 22 September 2009, released under the Freedom of Information Act.

-

See note 9(2)(b) of a Minute of a Meeting of the Board of Directors of Culture and Sport Glasgow, 2nd September 2009.

-

See note 10(5) of a Minute of a Meeting of the Board of Directors of Culture and Sport Glasgow, 25 November 2009.

-

See note 8(3)(b) of a Minute of a Meeting of the Board of Directors of Culture and Sport Glasgow, 2 September 2009.

-

According to page 17 of Ibid, investments fell from £523,000 at the end of March 2009 to £19,000 at the end of March 2010. This includes interest receivable and the net return on pension assets (which stands at zero at the end of March 2010).

-

Ibid, p. 25.

-

Glasgow City Council Financial Statements for the Year ended 31 March 2010 (Pre-Audit Inspection Copy), p. 86, which were open to inspection under the Local Authorities Act from 26 July to 13 August 2010.

-

See note on BAE Systems at: http://www.powerbase.info/index.php?title=BAE_Systems

-

In a World Health Organization report, published in August 2008, Glasgow is mentioned twice in a table on male life expectancy, showing that a man living in Lenzie can expect to live to eighty-two while his counterpart in Calton has the average life expectancy of just fifty-four. See Table 2.1 in WHO Commission on Social Determinants of Health, Closing the Gap in a Generation: Health equity through action on the social determinants of health (Geneva: World Health Organisation, 2008), available at http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2008/9789241563703_eng.pdf

To put this into even sharper perspective, men in India are expected to live eight years longer than those in the poorest parts of Glasgow. -

See notes 3 (7)(g)(iv) and (F)(dd) Minutes of Glasgow City Council 28 January 2010.

-

Gerry Braiden, ‘Councillors Lose Cash as ALEO Jobs are Axed’, Evening Times, 15 June 2011.

-

For a lyrical account of the council leader, Steven Purcell’s departure, see Clayton Z. Cross on The Absolute Limit, 5 April 2010 http://theabsolutelimit.com/?p=377

-

See ‘The New Bohemia’, op cit.

-

See Rebecca Gordon-Nesbitt, ‘Glasgow Life or Death’, Variant, Vol. 2, 41, spring 2011, pp. 15-20 http://variant.org.uk/pdfs/issue41/rgn41.pdf