Brattøra: Bridging the Gap Between Art and Urban Planning

Kunstneriske kompromisser i offentlige rom, Text Series, Simon Harvey 02.05.2011

For many of us Brattøra has been the place in Trondheim on the other side of the river where we go swimming, or catch a ferry somewhere else. Now of course it has Rockheim and other changes are afoot in this newish territory reclaimed from the sea. But, as yet, it still seems like a bit of a wasteland. Nevertheless, as we get used to the eastern part of the city coming to resemble wartorn Beirut with the digging operations for the new tunnel, focus has moved on to Brattøra as the next big urban architectural project.

Beyond that we have the issue of art.

Like most blank canvases this area calls out for some kind of artistic activity, and has a bit of a history in this respect: some years ago provisional permission was granted for a gallery here. There is now talk of an `art hotel` and, it is suggested, the planned open public space, Brattørtorget, that will welcome pedestrian visitors here when the new bridge is built over the railway tracks, as well as the breakwater/new beach, are to be adorned with sculpture.

There are also broader struggles for specific cultural space in Trondheim: for a kunsthall for instance, and the desparate need for a visible art scene. The city, it seems, is stirring out of its cultural conservatism to give contemporary art more ground. It is not easy for artists though. Despite the often generous funding of the social democracy, artists still have to perform. They must be agile, adaptive and adept; masters of funding application, managers of multifarious materials and resources, and skilled promoters – all matters of the harsh reality of making some space for themselves in the crowded landscape of urban and cultural change. And beyond this not so subtle work artists have to come up with beautiful art pieces, demonstrating lightness of touch and sensitivity to the environment, to please public and private sponsors, and at the same time to retain some personal integrity, and for their art not to be seen to be compromised by all these demands.

We have, then, in this art-architecture-urban planning game, Brattøra as a kind of case study, artists and architects as the on-the-ground players, but also the broader landscape of Trondheim as the potential ground for an art scene.

Behind this there is the SIM city-like game of the kunsthall: will it be in the west of the city beyond Ila, or in the east at Nyhavna, or perhaps in Brattøra itself, or heaven forbid, will there not be a cultural centre at all? The detailed and involved politics of the kunsthall are beyond my capabilities to assess, but I want to say a bit about cultural scenes and landscapes generally, finishing up with some speculation about potential approaches to art and public space that might be of some relevance to Brattøra.

First, not Trondheim. Beirut in fact. Not the eastern part of this city but the real Beirut, the one torn apart by civil war until relatively recently. This might seem like a perverse analogy to make but the matter that interests me is that both Trondheim and Beirut have been feeling their way towards an art scene where there is perceived to be either none, or a disfunctional one. Trondheim has its fair share of institutions that have their say in shaping the cultural landscape of the city. These are political, educational, cultural and commercial. Most prominent among them are the kommune, the university, and the oil and leisure companies (hotels, transport etc.) and together they produce an art scene of sorts, or, more accurately speaking, a number of layers or grids superimposed one upon the other which never quite align into a coherent and readable cultural map. Perhaps one of the functions of the kunsthall is to bring them together. As I said this is an art scene of sorts but one that is considered unsatisfactory, particularly from a contemporary art perspective.

First, not Trondheim. Beirut in fact. Not the eastern part of this city but the real Beirut, the one torn apart by civil war until relatively recently. This might seem like a perverse analogy to make but the matter that interests me is that both Trondheim and Beirut have been feeling their way towards an art scene where there is perceived to be either none, or a disfunctional one. Trondheim has its fair share of institutions that have their say in shaping the cultural landscape of the city. These are political, educational, cultural and commercial. Most prominent among them are the kommune, the university, and the oil and leisure companies (hotels, transport etc.) and together they produce an art scene of sorts, or, more accurately speaking, a number of layers or grids superimposed one upon the other which never quite align into a coherent and readable cultural map. Perhaps one of the functions of the kunsthall is to bring them together. As I said this is an art scene of sorts but one that is considered unsatisfactory, particularly from a contemporary art perspective.

Beirut, on the other hand, coming out of years of protracted and devastating conflict had little of this institutional framework. In a published conversation between the writers, art theorists and artists Stephen Wright, Walid Sadek, Bilal Khbeiz and Tony Chakar that were part of the exhibition Out of Beirut at Modern Art Oxford in 2006, the issue of an art scene in the city was central to the discussion. The absence of cultural organizations and of an `art world`, it was suggested, gave a paradoxical freedom to practice: because there was no official room for making art there was all the room in the world. Whereas privileged centres of art production might have a kind of semi-autonomy from commercial and political pressures that enables activity to naturally spread out into fields of `non` or anti-art, Beirut artists had to play a more tactical game, installing themselves on borderlines of the fragmented city and also on thresholds between different genres such as documentary and fiction. In other words, in order to produce an art scene, to deal with the war, and imagine a future, the old staples of conventional object production in traditional public spaces with the backing of stable cultural organizations were no longer available, and improvisation was key. Instead the art scene revolved around cafes and cultural `associations` (enthusiastic and heroic proto-institutions) such as the Beirut Theatre and Ashkal Alway that promoted cultural debates in public spaces. This led to something more than semi-autonomy and it flourished in an `extra-artistic`, `extra-disciplinary` public sphere; a kind of grass roots emergence of an art scene.

Beirut, on the other hand, coming out of years of protracted and devastating conflict had little of this institutional framework. In a published conversation between the writers, art theorists and artists Stephen Wright, Walid Sadek, Bilal Khbeiz and Tony Chakar that were part of the exhibition Out of Beirut at Modern Art Oxford in 2006, the issue of an art scene in the city was central to the discussion. The absence of cultural organizations and of an `art world`, it was suggested, gave a paradoxical freedom to practice: because there was no official room for making art there was all the room in the world. Whereas privileged centres of art production might have a kind of semi-autonomy from commercial and political pressures that enables activity to naturally spread out into fields of `non` or anti-art, Beirut artists had to play a more tactical game, installing themselves on borderlines of the fragmented city and also on thresholds between different genres such as documentary and fiction. In other words, in order to produce an art scene, to deal with the war, and imagine a future, the old staples of conventional object production in traditional public spaces with the backing of stable cultural organizations were no longer available, and improvisation was key. Instead the art scene revolved around cafes and cultural `associations` (enthusiastic and heroic proto-institutions) such as the Beirut Theatre and Ashkal Alway that promoted cultural debates in public spaces. This led to something more than semi-autonomy and it flourished in an `extra-artistic`, `extra-disciplinary` public sphere; a kind of grass roots emergence of an art scene.

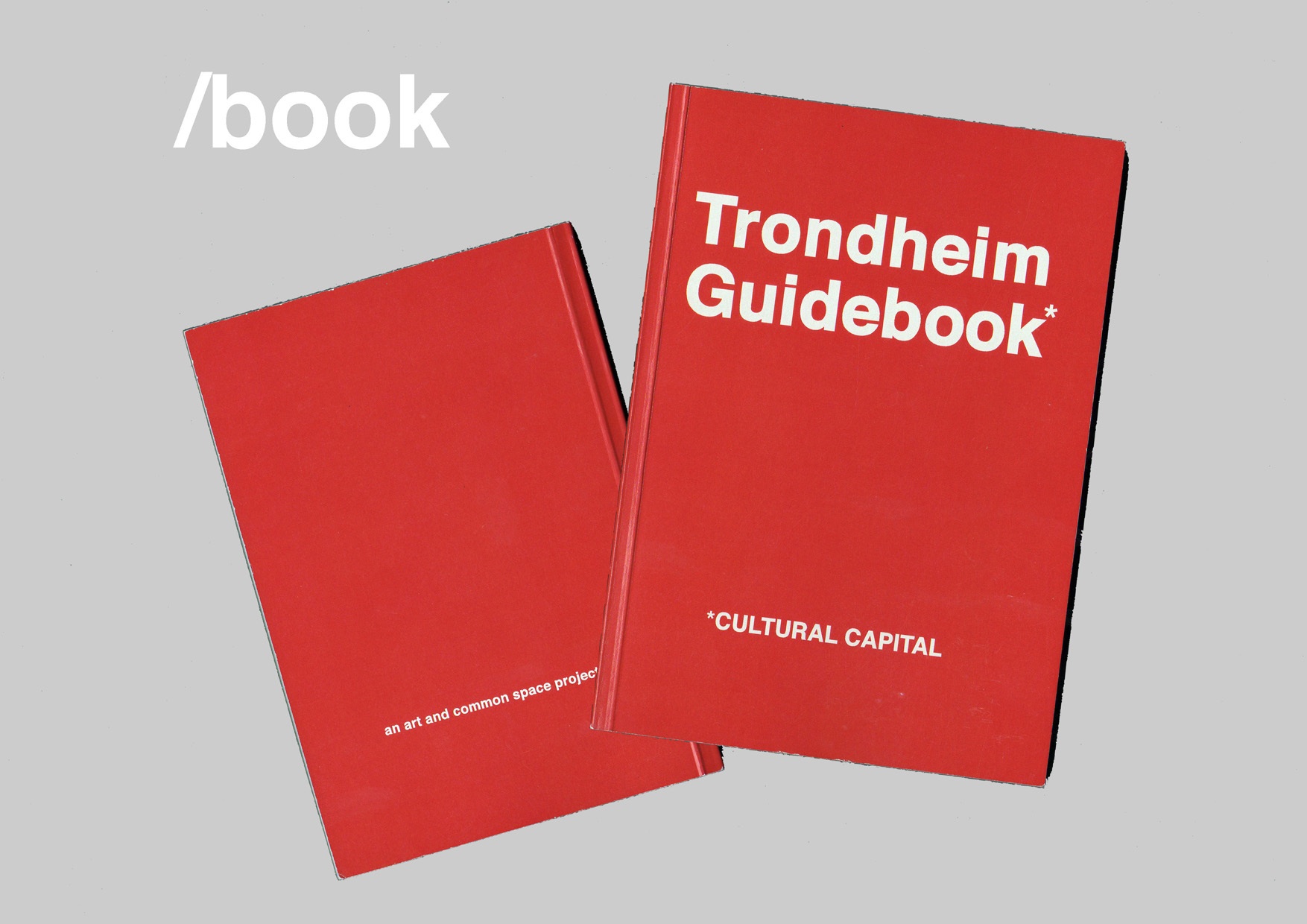

Some here in Trondheim have suggested that a vibrant art scene will only come from grass roots activity. To a large extent I would agree with this. It is the smaller and medium sized galleries in Trondheim – Blunk, Babel, Gallery KiT and TSSK – that are trying hardest to  make a scene here and to be seen. But it is hard for them, and perhaps the scene, if there is one, is also taking place in more unexpected and dispersed places. I work with a programme at the Trondheim Art Academy called Art and Common Space (Kunst og Fellesskapets Rom) and last year the students produced an alternative guidebook to the city. One of the things that emerged in the making of this book was that there was a diverse range of cultural activities going on that would fall outside of a conventional notion of an art scene but that, through this kind of mapping (the guidebook), might be imagined to be a part of it. An art scene in the city could then be thought of as a `territory of difference`, more akin to the informal scene in Beirut than to the ill-fitting superimposed cultural grids – gridlocks – that are mapping out the future of Trondheim from above.

make a scene here and to be seen. But it is hard for them, and perhaps the scene, if there is one, is also taking place in more unexpected and dispersed places. I work with a programme at the Trondheim Art Academy called Art and Common Space (Kunst og Fellesskapets Rom) and last year the students produced an alternative guidebook to the city. One of the things that emerged in the making of this book was that there was a diverse range of cultural activities going on that would fall outside of a conventional notion of an art scene but that, through this kind of mapping (the guidebook), might be imagined to be a part of it. An art scene in the city could then be thought of as a `territory of difference`, more akin to the informal scene in Beirut than to the ill-fitting superimposed cultural grids – gridlocks – that are mapping out the future of Trondheim from above.

This, then, might be a problem in the Brattøra project regarding its secondary phase – the installation of public art. Perhaps it is all a bit rigid, and somewhere in this heavy-handedness the lightness of touch of the artist is potentially compromised. It might also be affected by more general challenges that art often faces in relation to architecture. Art often seems to come after the fact: after the space is negotiated, towards the end of the architectural timing of the project and back towards which artists are sometimes reeled in like defeated fish. Is it any wonder then that they might feel outside or beyond the core planning of the new city?

This `beyondness` is both a problem and a possibility. On the one hand art is made to somehow fit in, after the fact, and artists are expected to compromise with their public art works that come to adorn the gaps between the buildings long after the architectural and topographical footprint has been decided, funded and concrete poured into the holes. On the other hand contemporary art is all about the beyond; about speculation and encounter with the other, and opening up other worlds.

How, then, might art practice weave itself, in more timely, integral and meaningful ways, into the fabric of this new vision for Brattøra? Some of the work that we do in Art and Common Space might offer cues to other approaches to public art practice here.

As one walks into Brattøra, as the new hotel goes up in front of Pirbadet, and Rockheim imposes from the left, one wonders where art might possibly be installed here. It is said that art, like all construction, builds on something else, but the difference between buildings and art is that whereas real estate takes the place of something, much contemporary art doesn’t colonize the ground, it takes place only in the sense of performing, happening – a process. The word `installation` implies taking a stand, but installations are also open-ended, affective, and only partially perceptible. If they involve emplacement they only do so in relation to movement. Of course good architecture takes all of this into account as well, but why then, if art and architecture have the same concerns and potentialities, do they so rarely take place simultaneously and in collaboration? Ultimately they inhabit the same landscape.

The term `landscape` gives us another clue as  to the experimental and speculative possibilities for art and architecture to operate in tandem. It derives from the Dutch word landschap which in the seventeenth century meant land that could be reproduced by a surveyor or artist, represented in a map or a painting. In England landskip came to mean the view, or scene, often observed from an elevated vantage point. But one can’t see very much in Brattøra; too many buildings and too few views. One of the stated aims of the urban development here is to put Trondheim back in touch with the fjord, but as with the developments just behind Solsiden, the buildings have little affective relationship with the sea; they are more like sea defences than thresholds to the wonderful fjord. So we must find some escape from these narrow gullies between the none too impressive buildings that are going up. Here the word `scape`, sometimes even used in the compound `artscape`, gives us another cue. On the one hand it is the shaft of a column or plant – all very formal and in place – but it is also related to the word `escape`. It would have been nice if the new development offered something different, an escape from the grid of the centre of town, and the corresponding gridlike thinking of many urban planners.

to the experimental and speculative possibilities for art and architecture to operate in tandem. It derives from the Dutch word landschap which in the seventeenth century meant land that could be reproduced by a surveyor or artist, represented in a map or a painting. In England landskip came to mean the view, or scene, often observed from an elevated vantage point. But one can’t see very much in Brattøra; too many buildings and too few views. One of the stated aims of the urban development here is to put Trondheim back in touch with the fjord, but as with the developments just behind Solsiden, the buildings have little affective relationship with the sea; they are more like sea defences than thresholds to the wonderful fjord. So we must find some escape from these narrow gullies between the none too impressive buildings that are going up. Here the word `scape`, sometimes even used in the compound `artscape`, gives us another cue. On the one hand it is the shaft of a column or plant – all very formal and in place – but it is also related to the word `escape`. It would have been nice if the new development offered something different, an escape from the grid of the centre of town, and the corresponding gridlike thinking of many urban planners.

In January of this year a collaborative project involving art, architecture and art critic students from the NTNU; Eksperter i Team (EIT) initiative (a course requirement for Masters students at the university) looked at Brattøra as part of their work. They proposed that the railway goods yard behind the station, which will eventually be re-sited to somewhere near the airport, should not be built upon but instead turned into a park, and in that park, like the Serpentine gallery in Hyde Park in London, should be sited the new kunsthall. The thinking behind this park is that there isn’t enough space, especially green space that might offer an all-year round escape from the busy centre of town. There isn’t quite the possibility for an artscape other than the summer orientated beach area which anyway would be on the fringe of Brattøra.

We need to get away from a modular way of thinking. Art and Common Space is interested in the possibilities of process-thinking, and dynamics that do not cement down art or architecture. In this alternative landscape, seeing is not necessarily primary. Senses of smell, touch and sound come into play. Art should both listen out and be listened for. Temperature, texture, rhythm, among other overlooked sensations, should all be part of the embodied experience of both the artistic and architectural landscape. Artist and cultural theorist Tacita Dean and Jeremy Millar articulate this very well in their book/exhibition project Place: «…interpenetrations and superimposition, whose scale, force and rhythm are engaged in an ongoing movement of shifts, rolls and waves, all of which generate new senses of place, or new senses of the same place». The quantum minutiae of the art and architectural experience should all be taken into account. Another aspect to this pluralistic and complex notion of site development is that it should not necessarily produce consensual space. Agonistic space, in which differing viewpoints contradict each other and in which varying interests overlap should be a possibility in both art and architectural thinking.

Brattøra, then, and perhaps much more public art work generally, could be the site of othering, of thinking beyond. As philosopher Michel Foucault put it : «act socially» but «think otherwise». The experience of good planning should evoke stories: not ones representing an ideology or dominating interest but it should imagine places where stories and storytelling – spaces of encounter – can offer continuous potential for development in this `otherwise` manner. The anthropologist Tim Ingold refers to this experience as «knowing as we go, not beforehand».

For both artists and architects this would entail a  lightness of touch that is often lacking in monumental bronze sculptures and block after block of defensive architecture. This is not to say that one must reject all object or representational work – the Artscape Nordland project is a very good example of how objects still work in landscape – but in the more confined landscape of Brattøra perhaps a certain subtlety and a deftness of touch is required. As the above referred-to Lebanese artist and architect Tony Chakar has stated: «what is brought into the present should be intelligently thought out, not an empty series of signs». After all, art practice is never this simple and indeed is sometimes referred to as an asignifying practice.

lightness of touch that is often lacking in monumental bronze sculptures and block after block of defensive architecture. This is not to say that one must reject all object or representational work – the Artscape Nordland project is a very good example of how objects still work in landscape – but in the more confined landscape of Brattøra perhaps a certain subtlety and a deftness of touch is required. As the above referred-to Lebanese artist and architect Tony Chakar has stated: «what is brought into the present should be intelligently thought out, not an empty series of signs». After all, art practice is never this simple and indeed is sometimes referred to as an asignifying practice.

The contract between artists, architects, planners, the general public, and those with the money should have as their mantra the phrase `social imagination`. With this in the mind of all parties, the negotiation between funders and artists would feel much less like a compromise and more like a collaboration. Ultimately though, artists and architects do different, if overlapping things, and some very different things from urban and social planners. It takes a certain imagination to respect this, but if this trust is a part of a social-aesthetic contract then more autonomy for the artist might ensue.

Artikkelen er en del av tekstserien Kunstneriske kompromisser i offentlige rom

Illustrasjoner:

1. Clarion Loves Trondheim, signal-kongresshotell, Brattøra (foto: Andreas Hvidsten)

2. Bernard Khoury, BO18 Music Club. Built 1998. Out of Beirut 2006, Courtesy the artist

3. Walid Sadek, Learning To See Less, 2009 courtesy of the artist

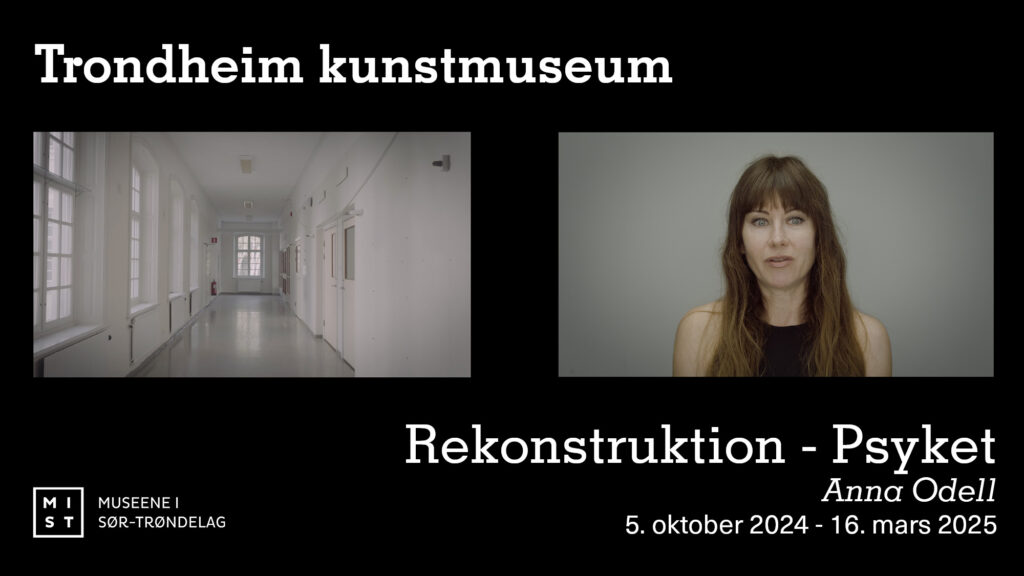

4. Trondheim Guidebook, Art and Common Space, KiT, 2010

5. Sentralstasjonen, Trondheim (foto: Andreas Hvidsten)

6. Tony Chakar, Catastrophic Space: a voice-over Beirut, http://www.partizanpublik.nl/catastrophicspace/site.html